|

It was freezing cold before the Taranaki Nurses Alpine Tramping club even began their climb of Mt Taranaki. But then it was mid winter - July 1953.

While not exactly inexperienced, a winter climb is not something for the faint of heart. There were 31 in the group, 18 nurses, nine members of the Taranaki Alpine Club and four visitors and they had planned a day trip, up and back. With them was Keith Russell, the club's most experienced guide. They set off from Tahurangi Hut late, it was 11.30am before the climb started. There was snow down to 660m. Russell had organised the group in six rope parties. Everyone was well dressed for the cold. The ascent went well, with the inexperienced learning how to use the rope and how to stop themselves sliding. At the top it was even colder. But it was late and the group opted to skip lunch and begin down. As they began, the wind picked up. Down at the hut, those waiting were worried, it was later than they liked Three club members decided to go up to meet them. They found the parts of the group cold, hungry, fatigued, their hands so frozen they were barely able to hold the ropes. One of the groups on one rope got into trouble, falling and one of the club members tried to stop it, getting in the way deliberately to try and stop the slide. On and on they fell until a club member managed to use an ice axe to stop them, only metres from a steep bluff. By now it was dark. As another group tried to descend further, one of the women fell. One by one, those on her rope, and Russell went over the 30ft bluff. One of the other guides got to the hut and the call went out for help. By the time help arrived, two had died and five were seriously injured. The rest of the climb group made it to the hut but needed to be treated for exhaustion, exposure and frostbite. It took hours to get the survivors down and one of the injured who had been recovered, died during the wait. In the dark and now snowing, people were slowly taken to safety. Those who died were Keith Russell, Andrew Lornie, Ruth Caldwell, Janet Cameron, Julie Casells and Ellen McBeth, who had broken her leg and survived the trip down the mountain but died the next day in hospital. It’s recorded as New Zealand’s deadliest alpine disaster. Ellen McBeth is buried in Te Henui Cemetery. Photo by Sulthan Auliya.

0 Comments

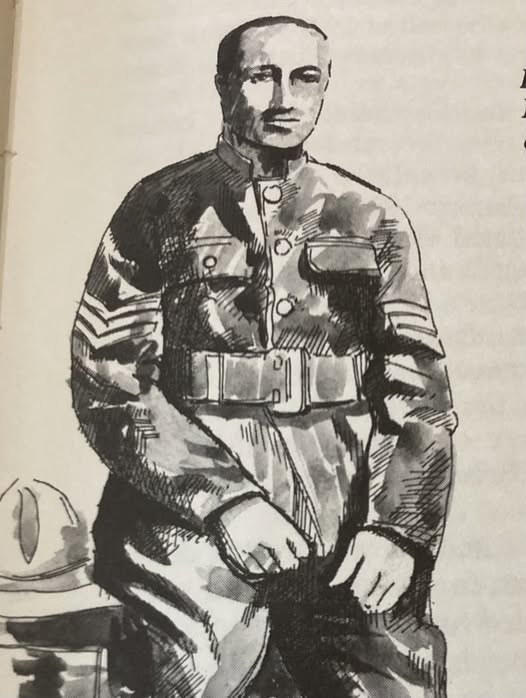

Across the horrors of No Man’s Land at the Somme a Kiwi lay in wait. He had a gun at the ready and was known as a crack shot.

A glimpse of a head and Dick Travis shot, taking out another enemy soldier. Dickson Cornelius Savage was born on April 6, 1884, to James Savage and Frances Theresa O’Keefe in Opotiki. After a few years of schooling he left to become a shepherd, drover and farmhand excelling in horse breaking. But an argument with his father saw him leave and head to Gisborne. He moved again to Southland after he was believed to have got a girl in trouble where he took the name Richard Charles Travis. He worked there for a while then enlisted in the 7th (Southland) squadron of the Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment in Invercargill. He sailed in December 1914 and landed in Egypt and immediately snuck off to Gallipoli. He was returned and given 14 days detention. It would set a theme. He was a rule breaker, but always for a good cause. Dick did take part in the final weeks of the Gallipoli campaign and was particularly noted for scouting. An injury to a knee led him to transfer and he went to France in March 1916. He hated sitting and waiting so alone and at night, he would undertake scouting trips into no man’s land, mapping out the area. Senior officers quickly saw how valuable his information was. A few months later he got a special mention for a daylight search for wounded New Zealand raiders and the recovery of equipment. Travis displayed 'conspicuous gallantry' on 15 September 1916, eliminating several German snipers during the Somme offensive, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He made sergeant and was given command of the battalion's new sniper and observation section. 'Travis's Gang' became proficient in scouting enemy defences and capturing enemy troops for interrogation. He was casual about rank and dress regulations but meticulous about careful planning, as well as daring and resourcefulness of his anti-sniper work and lone patrols. Travis was awarded the Belgian Croix de guerre on 15 February 1918, and the Military Medal in May 1918. On 24 July 1918, in broad daylight Travis destroyed an impassable wire block in front of the enemy lines prior to the attack. He then captured two enemy machine-guns, shooting down 11 Germans. He was killed by shellfire the following day, and was buried at Couin in France on 26 July. The entire New Zealand Division mourned his loss. For his 'most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty' on 24 July, Travis was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Lest We Forget Charles Gifford could rightfully be called the New Zealand moon man.

It was his theory that craters on the moon were caused by impacts of meteors that proved to be the correct one. Before that, it was believed the craters were caused by volcanic activity. Gifford was born aboard the ship Zealandia of the Cape of Good Hope on April 18, 1861 to Sarah and Algernon while on their way to New Zealand. They were headed to Waitaki parish where Algernon was to be the clergyman. They settled in Ōamaru where Charles (whose first name is actually Algernon but called Charles) attended the grammar school. Still in his teens, he was sent to England for more education, and obtained a degree in mathematics. After coming back to New Zealand he got teaching posts. He was influenced by professor of chemistry and physics at Canterbury College Alexander Bickerton who had an idea of an impact theory. He published a number of papers about the idea. In 1895 Charles was head of the science department at Wellington College where he was hugely popular. In 1901 he married Susie Jones in Ōamaru and they had three children. He was enthusiastic about astronomy and was responsible for establishing the college’s observatory. He began writing articles for The Evening Post then reprinted them in a booklet called In Starry Skies. He lectured publicly and halls where he talked were often crowded. He owned his own telescope set up in a small observatory on his property at Silverstream, near Wellington. In 1924 and 1930 he published two hallmark papers in the New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology demonstrating mathematically that meteoric impacts were responsible for the formation of lunar craters. Gifford also took a keen interest in gardening, field geology and contemporary economics. He was also a respected explorer and one of the early photographers of much of the back country within New Zealand's South Island. In 1939, Mount Gifford in the South Island was named in his honour. He died at his home in Silverstream on February 27, 1948. The funds from a society he had started was gifted to the Carter Observatory and used to purchase telescopes for schools. The Gifford Fund of the Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand funds lectures by astronomers around the country. He was cremated at Karori Cemetery. Photograph by NASA. Frances Alda’s flamboyant life was the only thing that was bigger than the voice that made her one of the greatest opera singers of the twentieth century.

A lyric soprano, she was called one of the greatest voices of the century. She sang with the biggest names to take to a stage and truly embodied the word diva. But she did not start there. She was born Fanny Jane Davis in 1879 in Christchurch to David and Leonore. Leonore herself was from a musical family and wanted to continue her singing career, divorcing David the year after Alda’s birth. She took her and her younger brother to San Francisco and remarried but died of peritonitis in 1884 and the two children went to Leonore’s parents in Melbourne. Young Fanny Jane began her singing career in Melbourne in light operas and pantomime but with few opportunities she moved to Europe and changed her name to Frances Jeanne. There she learned her trade before debuting as Manon in Massenet’s “Manon” at the Paris Opera-Comique in 1904. In 1906 she stood in at Covent Garden for the other great Australasian soprano of the day, Nellie Melba. She caught the eye of conductor Arturo Toscanini and Giulo Gatti-Casazza who she would later marry. When they took over the New York Metropolitan Opera, Frances went with them. The relationship was turbulent but Frances did well in New York although the pair separated in 1928. She also recorded prolifically, both opera and more popular ballads and early on saw the possibility of using radio to bring opera music to large audiences. Frances was a proud and patriotic Kiwi and during a tour home in 1927 she heard traditional Māori music and went on to record several songs. Even though Australia tried to claim her, she wasn’t having any of it, giving interviews where she said she hated it, while New Zealand had many virtues. Larger than life, she had flaming red hair and a temper to match along with being skilled as her own manager and was considered a shrewd businesswoman used to dealing with unscrupulous concert promoters. Frances retired in 1928 but continued to do recordings and some vaudeville performances and adored travelling. She married Ray Vir Den in 1941. Frances Alda died in Venice on holiday in 1952 at the age of 83 and is buried in All Saints Cemetery in New York. Robert Dickie’s obsession was with stamps, but not in the collecting way.

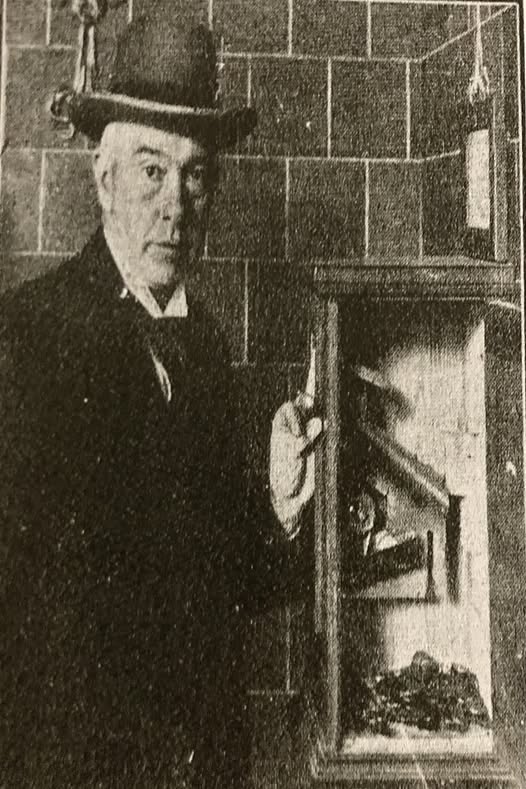

He was, in fact, sick of tearing up large sheets of stamps for sale when he worked at the Post Office. There had to be a better way, and by that he meant by machine. But it wasn’t until he saw his first moving picture that an idea came to him and he began working on it. What he was essentially thinking about was a vending machine for stamps. Robert James Dickie was born in London on December 30, 1876 and when he was 12 his whole family came out to New Zealand for a new life. Not long after he joined the Chief Post Office on Customs St in Wellington to work - something that would be part of him his whole life. It was the policy of the Post Office that all staff learned all the rolls and it was while he was at the front desk that he got bored with tearing up sheets of stamps. He sought out a mate to help him draft the idea which they then took to an engineer. Together they built the first machine and got a patent for it, essentially becoming the first to patent for a vending machine. The machine was greeted with quite a bit of publicity. But it did not solve the problem of stamps being in large sheets - Dickie lobbied the government to print them in a single roll but was refused so he bought the sheets, cut them up and created a spool machine for them to run through. In 1905, the machine was ready and Dickie presented it to the Post Office who liked it well enough but were not fond of the idea that the machine would sit outside with money in it at all hours. Dickie was crestfallen, but worked to solve the problem by buying the stamps all in one go so that the Post Office was not assuming any financial risk. At some point, some unknown Wellingtonian became the first person in the world to buy a stamp from a vending machine. In 1906, Dickie began marketing the machine to the world and went into a business partnership, coming up with marketing ideas, like setting one up in the House of Commons in Britain to help get approval. The machine won the gold medal, grand prize and overall diploma at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle and it went on to be used all over the world. By the time he retired the machines were in use around New Zealand. Dickie died on August 25, 1958 aged 81 and is buried in Purewa Cemetery. Photo from the Auckland Sun. Hester Maclean did not start out to be a nurse. It wasn’t until her father fell ill and needed to be nursed that she was inspired to study nursing.

Now she is a winner of the Florence Nightingale Medal and is sometimes thought of as the mother of military nursing. She was born in Sofala in New South Wales, Australia on February 25, 1859, to Harold and Emily Maclean and enjoyed a privileged upbringing and education. Her mother died in 1860 and she was raised by her step mother Agnes Campbell. But when her father became ill in 1889 she saw the nurse who helped him and resolved to seek nursing as a career. She began nursing training at Sydney's Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1890, qualifying in August 1893 before going into private nursing. After that she worked at a number of hospitals gaining a midwifery certificate and working at an asylum. Maclean applied for and got the post of assistant inspector of hospitals in New Zealand and held that position from November 1906 until her retirement in 1923. She was also designated director of the division of nursing in the new Department of Health in 1920. Considered a formidable woman, she was responsible for nursing and midwifery education and registration as well as assistant inspector of mental hospitals. She also believed in hard work which could be uncomfortable as members of a profession that gave service to mankind, Not all her ideas were progressive, she did not believe in the eight hour day, saying nurses needed to adjust their days to the needs of the patient. She oversaw the development of Plunket, tuberculosis, school and backblocks district nursing, independent midwifery, the Māori health nursing service and nursing training for Māori women. In 1908 she began to publish a nursing journal called Kai Tiaki (guardian) and continued it the rest of her life. Maclean was appointed matron in chief of a proposed military nursing reserve in 1911 and fought for the right of nurses to serve overseas. The New Zealand Army Nursing Service was established in 1915 and Maclean selected and equipped all army nurses during the war, making a point of seeing them off and greeting them on return. In April 1915 she escorted the first 50 nurses to Egypt herself, dealing with hospital placements, accommodation problems and disagreeable doctors and military personnel who refused to recognise nurses' officer status, a problem never fully resolved. She wanted to stay but was needed back in New Zealand, in part due to shortages in nursing staff, made worse by the influenza epidemic in 1918 and 1919. Her work was recognised in the awards of the Royal Red Cross (first class) in 1917 and the Florence Nightingale Medal in 1920. She retired in 1923 and she continued to live in Wellington and wrote her autobiography, Nursing in New Zealand. She died in Wellington on September 2, 1932, having never married and received a full military funeral before being buried in Karori Cemetery. The Progress was a steamer bound for Wellington from Lyttelton when it wrecked on the rocks on Owhiro Bay in 1931.

The night before, while crossing Cook Strait, the ship lost its tailshaft, which caused the propeller to fall off. Once off the Pencarrow lighthouse, the ship called for help asking for a tug. No tug was sent through a series of miscommunications. The ship kept drifting and off Lyall Bay the anchors were used to try and stop it. About 10pm the lighthouse advised the tug was on its way but it had not arrived by 11pm. With the sea getting rougher, the ship signalled again and was now told the tug would arrive around midnight. The Toia arrived and managed to get a line to the Progress but the rope parted. In the rough seas, the tug stood off until about 5.30am when it headed back in and a new tug took its place. For a while the anchors held. But eventually they failed and an attempt was made to bring the Progress into a sheltered bay. Instead she ran onto rocks about lunchtime. A sudden swell lifted the ship and brought her down sharply on the rocks, breaking her apart. From the shore men could be seen clinging to the ship and debris. Many of the crew began to swim to shore and many made it but were brought in bruised and bloodied from the rough seas and the rocks. Constable Fred Baker in charge of the Island Bay police commandeered a boat and headed into the rough water, trying to get to the men still holding on to the sinking ship. He had to be dragged ashore himself when the boat was upset. Another police officer also tried but was unable to get to them. Four men died, unable to make it to shore in the rough weather. Frederick Arthur Horace Baker was born on November 24, 1884, in Kaiapoi, to James and Martha Baker. He became a police officer and served in Wellington mainly in Island Bay for 14 years, leaving in 1936 to go to Levin. During the rescue of the men of the Progress he had managed to help ship fireman John Metcalfe who later died. During his attempts Baker himself received broken ribs and cuts and bruises to his back. He received the Kings Medal and the Royal Humane Society Medal for his attempts to rescue the men off the Progress. Baker died on March 22, 1962 in New Plymouth and is buried in Karori Cemetery. Daylight savings is just about over for another year. It would have made George Vernon Hudson sad.

George loved bugs. He loved them so much that all he wanted to do was collect them. George had been born in England on April 20, 1867, to Emily and Charles and by the time he was 14 he already had a large collection of bugs and had already published a paper. He was bullied at school for his interests. In 1881 he and his father moved to New Zealand where there was a whole new set of bugs to hunt for. After a short stint on a farm he went to work at the Post Office where he became a chief clerk for the whole of his working life. He published his first books on insects aged only 19 - the first of seven he would write. But he really wanted more bugs. In 1907, he went on the Sub-Antarctic Islands Scientific Expedition to extend the magnetic survey of New Zealand by investigating the Auckland and Campbell islands but botanical, biological, and zoological surveys were also conducted. Back at home he wanted more and more time and while he had time while he was shift working, he wanted more in the evenings. In 1895, he presented a paper to the Wellington Philosophical Society proposing a two hour extension to daylight hours. It wasn’t immediately taken up but he kept trying. New Zealand finally introduced Daylights Savings in 1927 with the Summer-Time Act. In 1933, George was the first recipient (together with Ernest Rutherford) of the T. K. Sidey Medal, set up by the Royal Society of New Zealand. With all his new daylight hours George went on to collect so many bugs that it became the biggest collection in the country, now housed in Te Papa. Among them are moths, butterflies, beetles, cicadas, grasshoppers and wētā, flies, wasps, and aquatic insects. Originally he intended to leave his collection - which his wife and daughter had helped him collect - to the British Museum, however an entomologist from the then Dominion Museum persuaded him to bequeath it to the national museum. The collection is still in use today by scientists. Bugs weren’t his only interest though. He also built and installed a telescope in an observatory at the back of his property in Wellington. George had married Florence Gillon, a teacher, in 1893 and had one daughter. He died on April 5, 1946 and is buried in the Saint Mary’s Anglican Churchyard in Karori. One of Australia’s best landscape artists is actually a Kiwi.

Elioth Lauritz Leganyer Gruner was born in Gisborne on December 16, 1882 to Norwegian bailiff Elliott and his Irish wife Mary Ann. But it’s unlikely he remembered the rural life of Gisborne in the late part of the 1800’s. His family moved to Sydney before he was a year old. But the rural life turned into the mainstay of his art. He began drawing early and by the age of 12 his mother took him to train with Julian Ashton, an art teacher and artist. He had to work, so at 14 took a position in a shop as a draper’s assistant to bring in money for his family after his father and older brother died. He kept painting on weekends and in 1901 he began exhibiting to the Society of Artists in Sydney and from 1907 began to get recognition. When a shop opened in 1911 on Bligh St to sell works of art from Australian artists Gruner took charge of it. He was continuing to work with Ashton and when Ashton became ill Gruner took over teaching, only to discover he hated teaching. He won the Wynne Prize (for painting or sculpture) in 1916 for a painting showing a farm at Emu Plains. He won again in 1919 for Spring Frost (the painting we show). The Valley of the Tweed was considered one of his best works and was a very large piece but his last - he rarely again painted anything big. In 1918 he, like so many others, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 4 June, went into Liverpool camp and was discharged on 31 December. A trip to Europe in 1923 extended for two years and allowed his painting style to mature and his attention to light - one of the things he was noted for - shifted. A one man show in 1917 allowed him to sell nearly everything he had painted. He then turned his attention back to the depiction of light and went on to create works that were considered his best. Gruner, a fair man with a square face was slow moving and slow spoken, was desperately unhappy and drank heavily especially in his later years. He never married, was shy and quiet and very sensitive to criticism about his work which led him to destroy pictures when he was unhappy with them, but also did not like to receive too much praise. He spent long periods in almost isolation to get his paintings done but in the city lived a stylish social life. Despite never marrying he had several children to several women. Throughout his life he suffered from inflammation of the kidneys and died at his home on october 17, 1939, and was cremated with a memorial at the Rookwood Memorial Gardens in New South Wales. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed