|

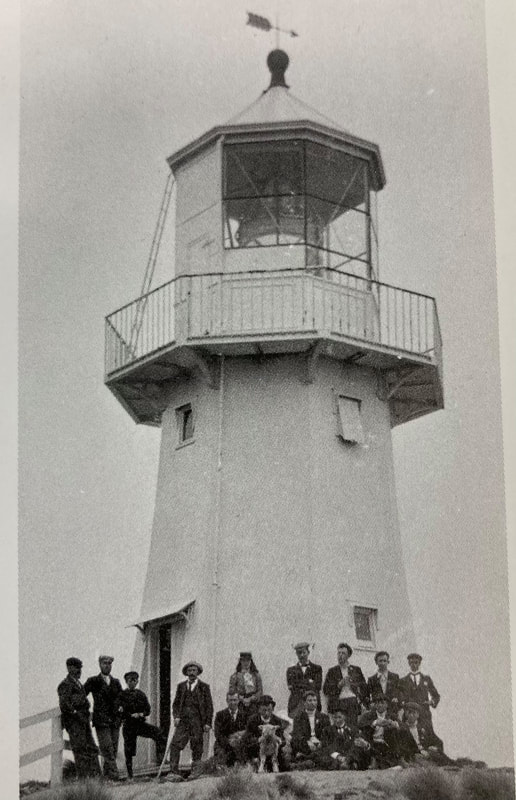

Mary Jane Bennett remains the only woman to ever become a lighthouse keeper in New Zealand, which she did in 1855 on the death of her husband George.

For 10 years she kept safe ships coming along the rugged coastline near Pencarrow Head. But it is only part of her story and her extraordinary family. Her husband George White Bennett was born March 2, 1814 at Whickham, County Durham, England, one of six children of George Bennett and Ann White. Meanwhile, Mary Jane Hebden - likely born in 1816 since she was baptised at Pateley Bridge in Yorkshire, on December 11 that year - was the oldest child of Mary and William Hebden. The pair met and fell in love, but when their parents did not agree on the match, they opted to come to New Zealand. George on the Cuba, landing in Wellington in January 1840, and Mary, then a governess, a month later aboard the Duke of Roxburgh. They married at St Paul’s Cathedral in Thorndon and George went from job to job for a while, farming and clerking including being the publican at one of the city’s first pubs, the Durham Arms. Initially there was just a beacon at Pencarrow (one of the first was blown over in the wind) but after the ship Maria went down off Cape Terawhiti with the loss of 30 people, calls for a lighthouse became loud. In 1852 George became the lighthouse keeper and he, Mary and their then five children moved out to the remote location. They had a small two room cottage, and operated a light from one of the windows to warn ships. It was hard, with little in the way of amenities. The cottage was not wind or waterproof and fresh water was a quarter of a mile away. It was sometimes so bad the family lived in a dugout, which had a stove in it. Their daughter Eliza died in the first year, then George was killed in a boating accident in 1855. The location of his burial is unclear. Mary, who was pregnant at the time, stayed on and in 1859 was appointed the official lighthouse keeper (with payment of £125 a year including firewood) when the light was changed to the permanent lighthouse there now. She was there when it was lit for the first time on New Year’s Day 1859. She had a male assistant, which would have been a real turnaround in those days. In 1865 she opted to take her children and return to England. Her three sons returned to New Zealand in 1871 and her youngest, William, returned to the lighthouse where he became assistant keeper. William is buried at St Albans Burial Ground in Pauatahanui. Mary never returned to New Zealand and died aged July 6, 1885 in Darce Banks, England where she had been born.

1 Comment

Four little bronze plaques at Old St Paul’s Cathedral in Wellington hold intriguing clues to four men who did a job barely anyone remembers.

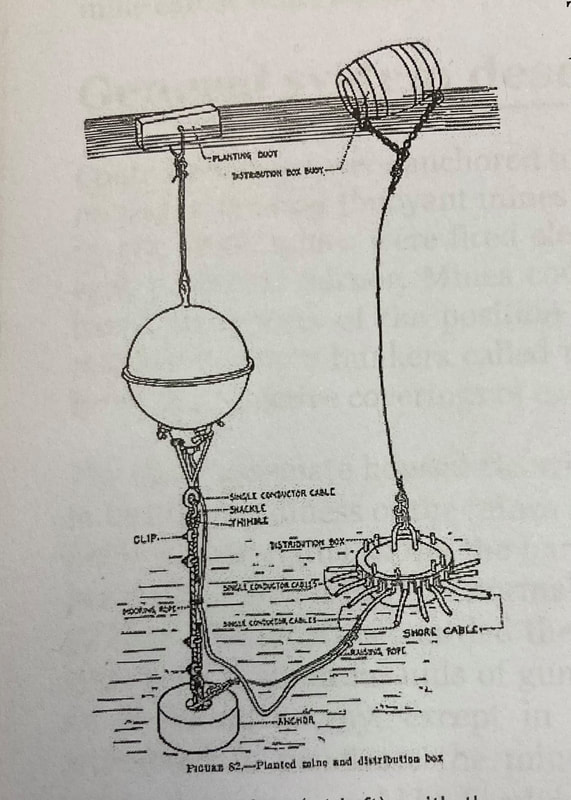

It reads “Erected by the Wellington Submarine Mining Volunteers.” What on earth (or sea) is submarine mining? In 1885, New Zealand was in the grip of the Russian Scare. It had started in 1873 when the news broke that a Russian warship had entered Auckland Harbour undetected. It turned out to be a hoax. But relationships between Russia and other countries were precarious with Russia seen as the aggressor. Full-blown alarm began in 1885, growing out of Anglo–Russian rivalry in Afghanistan and led to the building of major fortifications to protect New Zealand’s coastal cities. Which in turn led to the forming of the submarine mining volunteers who were responsible for coastal fortifications. These included gun emplacements, pill boxes, observation posts, underground bunkers which sometimes had interconnected tunnels, which held magazines, supply and plotting rooms and protected engine rooms supplying power to turrets and searchlights. There were even kitchens, barracks and quarters. There are still remnants of these to be seen around Wellington’s coast. The submarine miners were all volunteers under the control of the Permanent Torpedo Corps who were based in Shelly Bay in Wellington. There were 64 in all. By 1895 the coastal defences extended over the whole of the northern area from Scorching Bay to Shelly Bay. Their job was to maintain permanent mines that were laid in the harbour, and to see off the Russians, if they arrived, with flag signalling and other tasks. However not one of the men named on the plaque died as a result of their duties. Sapper Richard Penfold died in 1903 after accidentally being shot in the back at the former Polhill Gully Rifle Range. He lingered for five months in hospital before succumbing to his wounds. He is buried in the Oamaru Old Cemetery Even more tragically Percy Noel Wilson (and his younger brother Warwick) and Hugh Bramley were lost at sea. They had been sailing in the yacht Te Aroha around the Marlborough Sounds over the Christmas/New Year of 1903. They were due back in the harbour when the yacht was overwhelmed in heavy seas. Lance Corporal Ernest Edward Palmes died of illness in 1905, the son of the prominent family in Levin where he is buried in Levin Cemetery. The brass plaque was meant to hold many many more names of brave men but by 1908 the submarine miners were disbanded. Those partial to a drop of good old-fashioned beer may well know the name Henry Wagstaff – he was the founder of what became the iconic Tui Brewery in Mangatainoka. You may have seen Henry’s story and image featured on Tui Brewery’s website, in their marketing materials and even on the labels of their “Henry Wagstaff Special Brew” – all making him somewhat of a minor beer celebrity. But what you probably don’t know is that Henry lies forgotten in the cemetery across the road from the brewery in a grave with no headstone, from which (if he was able), he could keep a loving eye on the empire that he founded. Henry was born in the small village of Aldwark in the Peak District in Derbyshire, England in 1836 to Francis Wagstaff, a farmer, and his wife Elizabeth (nee Taylor). He was the 11th child out of a staggering 17. By the age of 15 he was working as a barytes grinder (barytes is a mineral containing barium). In 1860 he was working as a police sergeant in Bolsover, Chesterfield when he married Caroline Baggaley, six years his senior. They had two sons, Francis Henry in 1862 and Albert Edward in 1864, who died in 1868. By 1861 Henry had left the police and started his long-lived relationship with beer, first running a pub in Duffield, Derbyshire and then The Telegraph Hotel in Morledge, Derby. Then, sometime between 1881 and 1884, Henry left his wife and son in England and travelled to New Zealand. At some point Henry’s niece Mary Wagstaff, the illegitimate daughter of his oldest sister Matilda, joined him as his housekeeper (and possibly wife – although no marriage is recorded). Henry appears to have tried a variety of different jobs - manager of the Woodville Bacon and Cheese factory but he lost that job after a year-and-a-half. He tried sawmilling but after spending a small (borrowed) fortune on equipment, went bankrupt without felling a single tree, and the refurbishment of two houses which had to be sold to pay debts. By 1888, Henry was discharged from bankruptcy and announced he was starting a brewery in Mangatainoka. By March 1889 he had dug out a cellar nine metres long, seven metres wide and two metres deep, begun work on the three-storey building and purchased barrels ready to be filled with his ale. On May 1, 1889, the first brew from Henry Wagstaff’s ‘North Island Brewery’ was ready. Henry told the local newspaper he could produce 15 hogsheads (3700 litres) of beer a week and, most importantly, he could draw pure water from an onsite spring. Henry’s business boomed and orders for his beer flooded in from all over the county. Over the next few years he added barrel building and bottling plants and expanded the brewery with a new brick building. Henry also did not forget those to whom he owed debts from his failed sawmilling venture, paying them back even though he was no longer legally obliged to. Then in January, 1896 disaster struck. The brewery was seized by the Collector of Customs and Henry was charged with breaching the Beer Duty Act. Police alleged Henry had reused duty stamps and failed to record beer sales. He received a hefty fine. A few weeks later Henry announced he had sold the brewery to the firm of James Clarendon Ramsbottom Isherwood and Sons of Palmerston North. Isherwood handed control of the brewery over to his sons, who were apparently not able to manage the business, and within nine months he had lost the £1530 he had invested and filed for bankruptcy. The brewery was put up for auction, but failed to sell. Meanwhile, Henry started construction on a new brewery in Paeroa, and he and Mary left Mangatainoka. On July 1, 1896 Henry’s ‘Victoria Brewery’ opened for business. The Victoria Brewery went from strength to strength and the plant was expanded over the next few years. In October 1899, ownership passed to the Goldfields Brewing Company and Henry and Mary returned to Mangatainoka, where he set about fixing up the North Island Brewery. By April the following year the brewery started operations again, with Henry advertising; “Wagstaff’s hygienic beer is recommended by the medical profession” (gosh haven’t times changed). In 1903, Henry sold the brewery to brewer Henry Cowan, who introduced the “Tui” brand four years later. Henry and Mary (described in the Woodville Examiner as “his good lady wife”) built a cottage in Pahiatua and spent their days gardening and travelling. Henry died in Pahiatua on October 19, 1911 and two months later Mary returned to England. In his will he left £300, his furniture and personal items to his “niece and housekeeper Mary Wagstaff”. Henry’s beloved brewery was eventually sold to DB Breweries, which is now owned by Dutch brewing giant Heineken. We think that given Tui has co-opted Henry’s image and story into their marketing, it seems only fair that they honour their founding father with a headstone. Hopefully with some encouragement they might actually say “yeah! - OK”. William Harrington Atack was exhausted. A Canterbury rugby referee, he had spent hours running up and down yelling himself hoarse at players

At some point he put his hand in his pocket where the whistle for his sheepdogs was and an idea struck him. He used whistles on them, so why couldn’t he use whistles on rugby players? Hoping they did not think he was treating them like dogs, at the next game he refereed, in June 1884, he got the teams to agree. And for the first time a whistle, so common now, was used in a game of rugby. The International Rugby Board, in 1892, made it a requirement for a referee to carry a whistle (although there were only 10 accepted usages for it.) Atack was born in England in 1857. He, his parents William, a painter, and Mahala came to New Zealand in 1959 aboard the Cornwall, along with his sister who did not survive the trip. Atack was an excellent student, going to Christ’s College, often winning scholarships. He was an excellent rugby and cricket player, representing Canterbury at cricket after leaving school. He also won a university scholarship but instead opted to go into journalism, starting at the Lyttelton Times in 1875. He was a dedicated sports reporter. In 1886 he married Ada Mackett and moved to Wellington where he became the general manager of the United Press Association - which later became the New Zealand Press Association. He held that job for an astonishing 44 years. It was during his tenure that UPA took the huge step of ordering its first typewriter. Atack retired from the NZPA in 1930 aged 74, and died in 1946, aged 89. He was cremated at Karori Cemetery. A bite in the night

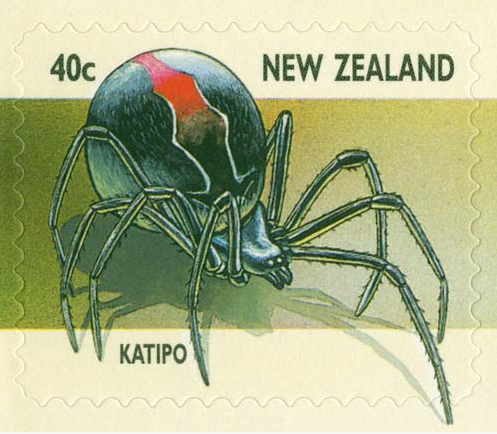

Fifty-one-year-old Wellington delivery man Malcolm Fraser lived a fairly ordinary life, but one small native New Zealand spider gave him 15 minutes of fame – in death. On February 5, 1891, Fraser became one of only a handful of recorded cases of fatal katipō spider bites. Fraser immigrated to Wellington from Edinburgh, Scotland in 1880 with his wife and children. He lived in Tasman Street, Mt Cook and worked as an expressman – a person responsible for packaging and delivering goods. In January 1891 he attended a two-day Wellington Racing Club event at Hutt Park. He slept overnight in a tent at the racecourse and awoke on January 24 to see the spider inflicting a painful bite to his right forearm. Fraser returned home and spent an agonising night in his bed. On January 26, with his condition worsening, he consulted Dr McCarthy, who found the arm much inflamed. The doctor, noting his patient appeared to be suffering from blood poisoning, prescribed a Turkish bath to sweat the poison out. Despite the treatment, Fraser’s condition continued to deteriorate and on January 29 he was admitted to hospital, where he died seven days later. A postmortem was performed by Wellington Hospital’s medical superintendent, John Ewart, which revealed Fraser was not a well man before the bite. Dr Ewart told the inquest he did not believe it would have proved fatal to Fraser if his liver and blood had not been in such poor condition due to the habitual use of alcoholic spirits. Fraser’s wife Elizabeth and their children were left destitute following his death and the Evening Post newspaper began a subscription for their support. The newspaper reported that Fraser, who was the family’s breadwinner, had not worked since the nationwide maritime workers strike which ended in November 1890. While a bite from a katipō spider is an excruciatingly painful experience, the little spiders have a lot more to fear from humans than we do from them. Spider expert, Lincoln University’s Dr Cor Vink, told GI that New Zealand’s katipō population is in steep decline. Katipō live only in coastal sand dunes and much of this habitat has been lost or modified since European settlement. Katipō also face competition from the fast-breeding invading South African spider Steatoda capensis, commonly known as the false katipō, black cobweb spider, brown house spider or cupboard spider, which has become widespread throughout New Zealand, as well as in sand dunes. The introduced Australian red back spider, which is related to the katipō, is also a threat as male red backs and female katipō can breed and produce viable offspring. According to Dr Vink, one thing we can do to help keep katipō safe is not to take driftwood from beaches as this is one place the little spiders make their nests. Trail bike riding and four-wheel driving on dunes is also harmful to the spiders and their habitat. If you are unlucky enough to be bitten, ice and painkillers should be enough to get you through. For serious cases, an antivenom is available Records of fatal katipō bites are sketchy. There are reports of some fatalities among Māori pre-European settlement. In fact, the Māori name katipō translates as ‘night stinger’. Seven cases of fatal bites were recorded in New Zealand newspapers pre-1950, but it appears only Fraser’s death, which was attributed to erysipelas consequent on the bite of a katipō spider, was confirmed by a postmortem and inquest. Fraser is buried in Bolton Cemetery in Wellington. Bill O’Leary - better known as Arawata (now Arawhata) Bill - spent most of his life looking for treasure.

Legends of hidden treasure had circulated around Westland, especially of a sea chest of gold worth £30,000 buried near a river mouth by pirates who had fled the Australian goldfields or of a ruby mine, long since lost. Neither has ever been found. William James O’Leary was born October 8, 1865, the second child of a family of eight to Timothy O’Leary from Prince Edwards Island in Canada and Mary O’Connor who came from County Clare, Ireland. They had come to New Zealand in response to the discovery of gold in Otago. It was a hard life. The family lived first at Tuapeka where gold had been found before moving to Weatherstons near Lawrence. Like a lot of kids at the time O'Leary's formal education was minimal. He worked on stations in Maniototo county before heading to Queenstown where he started prospecting, moving around South Westland for 14 years before taking a job with the Westland County Council as ferryman on the Waiatoto River. He resigned in 1929 and the rest of his life was spent prospecting the river valley from where he got his nickname. But his obsession with gold might have come about as the result of a prank. A companion pretended to find a nugget which Bill refused to believe was planted. O’Leary also claimed to have found - then lost - a ruby mine in the Red Hills area. He was the perfect bushman, completely self-reliant. Happy with his own company, he was not, however, a hermit. He enjoyed meeting people. He finally retired in his mid-70s but still made prospecting trips. Still searching. In 1943 he went into a Dunedin home for the aged but hated the lifestyle and made several attempts to return to Arawhata. He never found any significant gold - or indeed - his ruby mine. He died in Dunedin Hospital on November 8, 1947. His name lives on as two passes, one in the Mt Aspiring National Park and west of Lake McKerrow bear the O’Leary name. He is buried in Andersons Bay Cemetery, Dunedin with a simple headstone, funded by a public appeal, that records both his names. Cars are everywhere now and they make us fume. From traffic jams to road rage.

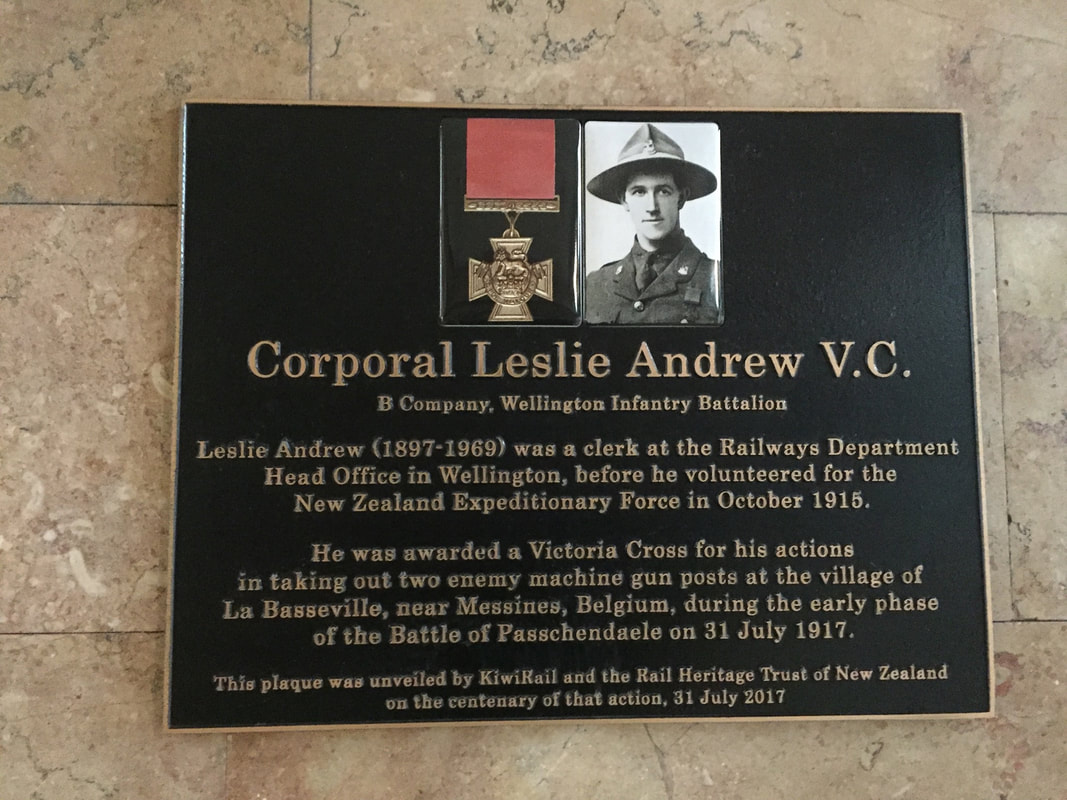

But there was a time when there were only two. William McLean, in March 1898, imported the first two cars New Zealand had ever seen. Two Benz, made for him in Paris, arrived in Wellington to newspaper headlines. One could seat three passengers and the other two. McLean, born in Scotland in 1845, was the youngest son of John McLean, a shoemaker in Grantown, Scotland. He arrived in Dunedin on the Dauntless. He tried gold mining, being a teacher then moved to Wellington 1884 where he was an auctioneer. He was also a Liberal Party Member of Parliament. The McLean Motor Car Act of the same year laid out the rules by which cars could operate - going no faster than 12mph and being lit after dark. Even then McLean managed to also have the first car crash in New Zealand - driving one of those imported cars for the very first time. With spectators watching in awe he started off on Kent Terrace, promptly failed to take a bed and hit the Basin Reserve fence. It wasn’t until two years later that the next cars came to Auckland. But this isn’t about William McLean (he’s buried in Karori cemetery). It’s about Janet Meikle, who inadvertently became famous for being the first person directly killed in a motor car accident in the country on September 8, 1906. Janet was the daughter of William Wright and Janet Kerslake. She was driving a 8-hp De Dion Bouton - the most common model in the country at the time - when she lost control while negotiating a steep narrow muddy descent on the family farm Table Downs in the Washdyke Valley, about 5km from Timaru. While cars were slow they had little in the way of safety features. An account in the Otago Witness newspaper said Janet was driving and while descending the bank the car went over the edge and through a wire fence. Her husband John was thrown out but she was pinned underneath and suffocated from the weight. Janet had been an experienced driver, many rural women were, out of necessity. The South Canterbury Automobile Club expressed its regret and sympathy and asked that its members attend the funeral three days later – ‘without cars’. Janet was 38 and she and her husband had one child. Her headstone in Timaru Cemetery records that she died from a motor accident. Every day commuters walk through the beautiful front foyer of Wellington’s railway station without seeing the plaque on the wall that commemorates a war hero.

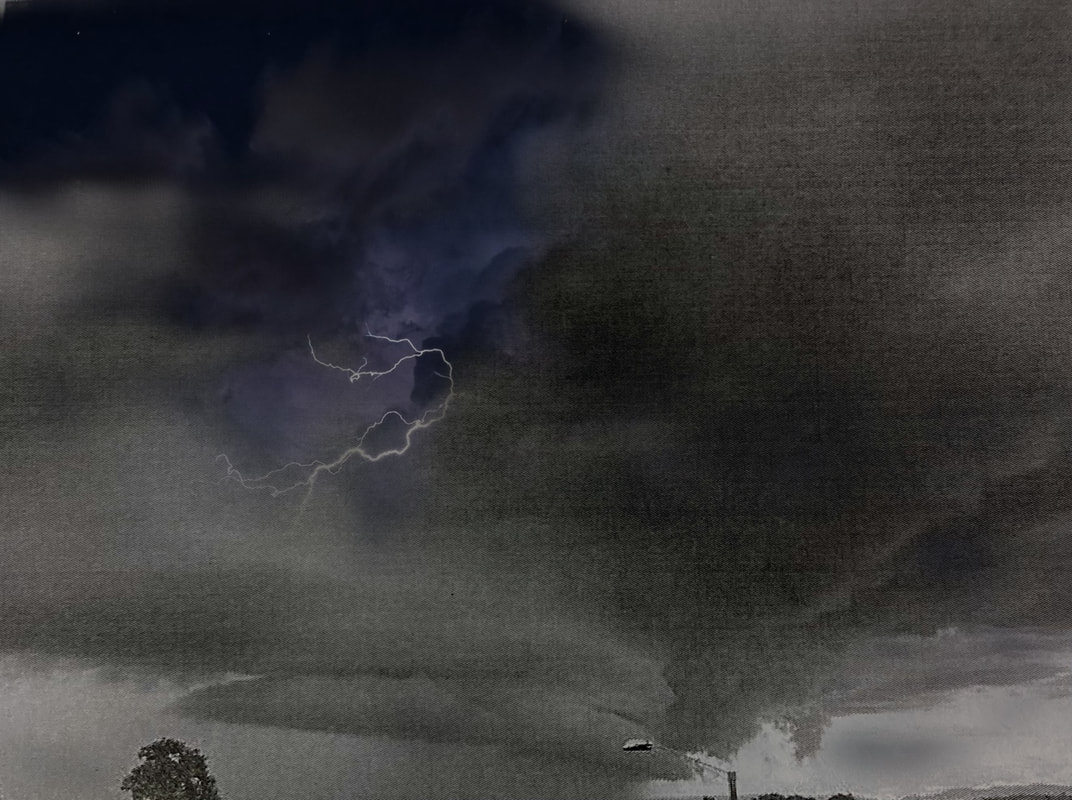

Leslie Andrew was a Wanganui boy but he was adopted by Wellington after he worked as a clerk at the Railways Department office before volunteering to serve in the Great War in October 1915. Born on March 23, 1897, in Ashhurst in the Manawatu, the son of the headmaster of a local school William Andrew and mother Frances Hannah, he grew up in Whanganui. After completing his schooling he worked for a solicitor before moving to the New Zealand Railways Department. He had gained valuable military service experience with the Territorial Force as a cadet which led to his eagerness to go to war. He wasn’t supposed to, he was underage at 18 and lied about it to join the New Zealand Expeditionary Force shipping out in May 1916. By September 1916 he had arrived in France and fought with the 2nd Wellington Battalion on the Somme before being wounded. During fighting around the tiny village of La Basseville, near Messines, in Belgium, then Corporal Andrew was leading men to destroy a machine gun post. He noticed a nearby machine gun post that was holding up the advance of another platoon. He diverted his force and removed the threat then led his men on to the original target. Despite being under continuous gunfire Andrew and Private Laurence Robert Ritchie kept going, taking out the post. He received a flesh wound to his back. He was awarded the Victoria Cross for his “cool daring, initiative, and fine leadership, and his magnificent example was a great stimulant to his comrades”. At 20 years old, he was one of the youngest New Zealanders to be awarded the VC. After further action he was sent to England for officer training and was there when the war ended. It was there he met Bessie Ball from Nottingham and married her. They had five children. Andrew opted to become a professional soldier and came back to New Zealand where he was appointed adjutant of the 1st Wellington Regiment. At the outbreak of WW2 Andrew, now a major, was seconded to the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force then appointed commander of the 22nd Battalion. They sailed in May 1940 to the Middle East but were diverted by the invasion of (then) Holland and Belgium. From there he went to Egypt and then Greece leading the battalion through the Battle of Greece. Evacuated to Crete, Andrew was ordered to hold Point 107, the dominant hill overlooking the airfield. Heavily bombed and with communications lost, they eventually had to withdraw After heavy losses in Crete. The battalion withdrew to Egypt to rebuild. When his commander was captured in 1941, Andrew was given temporary command, earning a Distinguished Service Order for his leadership. In 1942 he gave up his command in order to return to New Zealand where officers were needed to oversee home defences with the entry of Japan into the war. He led the Wellington Fortress Area for the rest of the war. Andrew died on 8 January 8, 1969 at Palmerston North Hospital after a brief illness and is buried at the Levin RSA cemetery. His VC was one of the ones stolen from the National Army Museum in Waiouru and later recovered. A large number of his descendants were at the unveiling of the railway station plaque 100 years after the battle for which he was awarded his VC. As a wild storm bashed the country this week, some needed to be evacuated, some recorded snow in Wellington, roads were closed and people shivered.

New Zealand has had its fair share of horrible storms, with the collision of two storm fronts in 1968 sinking the Wahine ferry being one of the most memorable. But there have been plenty of others. In February 1938, it did not seem like there was a storm. The worker’s camp on the banks of the Waiau stream, in the Kōpuawhara Valley at Kaiangapiri near Mahia, set up for the workers on the Napier-Gisborne Railway line, was bedded down for the night when disaster struck. The stream was already in flood, but at 3am a huge wall of water five metres high carrying logs, rocks and bridge timbers, created by a cloudburst, swept through, taking most of the camp with it. In its aftermath 20 men and one woman had died. A workman, who was awake, Tom Tracey, 44, tried to warn the camp by banging on the cookhouse gong. He could have escaped but chose to stay and try to alert the camp. He tried running around the camp banging on doors but to no avail. He was swept away in the waters. Many tried to take refuge on the roof of their huts but the huts themselves were swept away by the force of the water. Only those who managed to get on to the roof of the cookhouse survived. One man, Frank Fry, 51, left the safety of the roof to look for 22-year-old Martha Quinn but was swept away. He is buried in Wairoa. The Cameron family, caterer Harold, his wife, daughter Joan and son Harold, 17, managed to escape, with Harold junior rescuing another man. Daughter Joan was saved by elderly Hugh McCorquodale who tied himself to a hut and held her above water for an hour. Five kilometres away was a second camp. They managed to survive because they had more time although a man camping nearby was killed. At an inquest, much inquiry was made about where the camp was placed. A railway engineer said he had considered the floodplain when he put the camp up and there was no sign of any flooding. The event was considered unprecedented. Two bodies, those of Ivan Martinac, 31, and Roderick Douglas Neish, were never recovered. Martha, a waitress in the cookhouse was the only woman to lose her life. A mass grave at the Wairoa Cemetery holds 11 of the dead. Martha is buried at Taruheru Cemetery in Gisborne where her parents lived. A huge amount of damage was done to bridges, lands and roads totalling well over $5 million in today’s terms. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed