|

Buried in debt, famous Dutch-born artist Petrus van der Velden ended up before a magistrate in a Wellington court. Unable to pay board and lodgings, he said he only cared about art. And he did what he usually did. He drew the courtroom scene before him.

Yet, today, he would be counted as one of New Zealand's premier artists with his works shown in galleries and private collections up and down the country. Indeed, Vincent van Gogh considered him a solid and genuine painter. Te Papa Tongarewa, in fact, had to re-catalogue 36 drawings supposed to have come from van der Velden after it was discovered they were by notorious forger Karl Sim - aka Goldie. Van der Velden was born on May 5, 1837 in Rotterdam to Jacoba van Essel and Joannes van der Velden. His artistic career started when he was around 13 with drawing lessons and he was apprenticed to a lithographer. He founded his own lithographic printing company in 1858. His earliest works date from around 1864 and he began studying at the academies of Rotterdam and Berlin and later stayed at The Hague until 1888. He had a tendency to work on series, like fisher-folk, down-trodden women and musicians. In 1890, supported by the founder of Sumner School for the Deaf, Gerrit van Asch, he, aged 53, and his wife, Sophia, a daughter and two sons moved to New Zealand. He settled in Christchurch and began teaching. Then he discovered Otira Gorge on the West Coast and started producing what would be his most famous set of works. A student recalled that when a storm brewed, van der Velden would go to the gorge and when it was sunny he would lie in the grass and sleep. In Art Society shows, his work was greeted with critical acclaim and one of his most famous paintings, Waterfall in the Otira, sold for £300 - which would be a great deal back then. In 1898 he and his family moved to Sydney, Australia but a year later his wife died and he ended up ill himself in a convalescent home. It was in Sydney he met the woman who was to become his second wife, Australia Wahlberg, and they moved to Wellington in 1904 where they married. It was in Wellington he got into serious financial trouble owing £73 for board to the landlord of the Bellevue Hotel in Lower Hutt. His answers to whether he could pay the debt were so confusing the perplexed magistrate appeared to think he might be a bit unhinged and would not make an order against him. On a visit to Auckland in 1913 he caught bronchitis, had a heart attack and died. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Waikaraka Cemetery.

0 Comments

Most New Zealanders have seen Richard Gross’s work, although they probably wouldn't know his name.

In fact, I walk past one nearly every day. So, with protesters at Parliament occupying the land around the Wellington Cenotaph, which is designed to memorialise the brave men and women who fought for us, I wondered about the man who created its striking sculptures. Turns out his works are all around New Zealand. Richard Oliver Gross was born on January 10, 1882 in Barrow-in-Furness, Lancashire, England to engine-driver father George and his wife Emma. He went to the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts where he studied under sculptor Albert Tofts. Living in South Africa in his 20s, he worked as an architectural carver. He married Ethel Jane Bailey on July 25, 1912. In 1914 they moved to New Zealand and turned to farming near Helensville. Gross became a director of the Kaipara Co-op Dairy Company. But, a sculptor at heart, he moved to Auckland where he set up a studio in Newmarket. He designed the statue of a soldier for the Clive war memorial in Hawke’s Bay - a soldier standing with his gun in front of him. He did not however sculpt that one. His first public sculpture was for a memorial in Cambridge in 1923 - a shirtless digger with sandbags at his feet. Other commissions quickly followed in association with two Auckland architects William Gummer and Malcolm Draffin. His work includes a male figure for the top of the Auckland Grammar School memorial, the lion at the base of the Dunedin Cenotaph, the fountain at the National War Memorial Carillon in Wellington, the delicate bronze frieze around the Havelock North memorial, the stone frieze around the Auckland war memorial museum. In Wellington he created the equestrian figure for the top of the cenotaph - called the Will to Peace and two panels of a call to arms relief. It was used officially on Anzac Day in 1931 and dedicated on April 17, 1932. It was after the Second World War he added the bronze lions on either side. Gross was known for his beautiful anatomical form of men - often reaching up and his fondness for lions. He was the first sculptor to build his own bronze foundry. There is a marble memorial to Labour leader Harry Holland by Gross in the Bolton Street cemetery. He also created a bronze Maori chief for the One Tree Hill memorial. Gross received a number of honours for his work including a CMG, commander of the order of St Michael and St George. Not content with being New Zealand’s premier sculpture he also painted watercolours and wrote poetry. He and Ethel had three sons. Billie who died at aged 13, and Richard - called Dick -who died in active service in North Africa in 1942, which of course added a poignancy to his father’s memorials. Richard and Ethel are buried at Matamata cemetery - with fittingly, a slab of polished granite with a bronze plaque with their sons names on it. Picture from the Te Papa collection by Leslie Adkin in 1932. The weeds in Alan Stuart James’ Motueka orchard worried him. He tried to keep on top of them, but they just kept coming back, and it played on his mind – constantly.

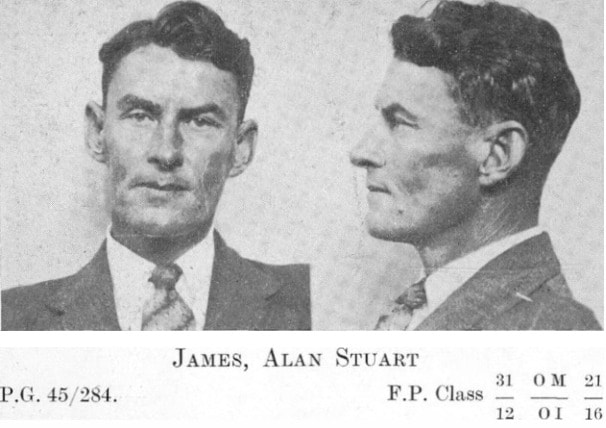

By his own admission, by 1944 James had become the living incarnation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s fictional murderer Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Publicly, he was an accomplished musician, cross-country-skier, and tennis player. His orchard was sited on a lavish 16-acre property with a large house, tennis court and pretty gardens on the coastal road at Moutere Inlet. He taught Bible classes at his local church and was happily married with four young children. Privately, James was always worrying. As well as fretting over those ever-growing weeds, he was also having several affairs, constantly worried about his elderly widowed mother, worried about a Japanese invasion, and, worst of all, harboured thoughts of disposing of his family – which worried him also. James was born in Feilding in 1906 to Edwin Tako James, an architect, and Mary Georgina Farmer. Edwin purchased the orchard in about 1918 and after his death in 1936, James took over running it. It was the same year that James married 21-year-old Marjory Eleanor Nottage, the daughter of a neighbouring orchardist. Over the next nine years the couple had four children: Eleanor in 1937, Corran in 1940, Berwyn in 1941 and Alan jr in 1944. All seemed happy with the family – except that Marjory suffered from a throat complaint – something that added to James’ worries. Then Marjory fell pregnant again – which James later said was an “unfortunate accident” as they did not want more children. On November 13, 1944, the couple went to their doctor to see if "something could be done", but the doctor refused. Upset at the news, they returned home. Later that night James put the children to bed and sat down to play the piano. He later told police that while he had not decided what he was going to do. “I thought how lovely it would be to be free from all these worries." While he sat playing, he fretted over the effect the pregnancy would have on Marjory and, of course, all the work that he had to do in the orchard. Leaving the piano, he picked up a wooden club and attacked his wife inflicting massive head injuries and breaking her arm. His oldest daughter Eleanor heard the fracas and got out of bed, giving Marjory time to flee to the neighbour’s house. James, realising that the club would not do the job he wanted, loaded his shotgun and killed all four of the children. He was arrested and during his interview with police claimed he was perfectly sane. “I want you to understand that I am not mad like you think … I knew all that I was doing.” He later said: “I often thought I should have told someone of the Jekyll and Hyde life I was living but I could not do so. Me taking Bible Class and knowing I was not what I should be.” James was charged with murder and was remanded to an asylum. On February 15, 1945, he pleaded guilty to four charges of murder. It was the first time in New Zealand history that anyone had done so as, prior to a law change in 1941, which abolished the death penalty the first time, the law did not allow for anyone to consent to being executed. (The death penalty was reintroduced in 1949). He was sentenced to life imprisonment. By 1963, James was out of prison, working as a storeman and living in Auckland with a new wife, Mollie. He died in 1978 and was buried at Purewa Cemetery. Marjory gave birth to a son in 1945. She divorced James in 1951 and remarried. She died in 1996 aged 85 and is buried alongside her four children in Wakapuaka Cemetery in Nelson. Pic: NZ Police Gazette See our work:http://genealogyinvestigations.co.nz/index.html Jack Allison has a dubious distinction in New Zealand history. He is mostly known for being one of the few people who have died in New Zealand after being struck by lightning.

It was reported in most newspapers of the time in 1923. But even though he came from the tiny Canterbury township of Cust, a place hardly anyone had heard of, and died in such an unusual manner, there was much much more to Jack. Jack was the son of Edward Allison and Julia (nee Worgan). Edward, a farmer from Lancashire, had come to New Zealand on the ship Blue Jacket in 1866. Edward worked initially as a shearer then in 1870 got a job with a threshing machine and purchased an interest in one. It led to a full plant of machines, which would have made Allison a wealthy businessman at the time. After his marriage to Julia, they had five children, three daughters and two sons. John Biddle Allison - known as Jack - was their middle child. Cust, a town around a railway line and station, would have been a rural ideal for a child. But it would also have been hard work. At the age of 20 he was in the newspapers for a completely different reason. He was awarded a certificate from the Royal Humane Society for saving 11-year-old Alice Morgan from drowning at Kairaki on January 19, 1911. In March 1917 Jack, like a whole generation of young men, signed up to fight in World War One. He was five foot seven with black hair and brown eyes. He was sent to Egypt from January 1918 where he served until he contracted malaria and returned to New Zealand in 1919 on the ship Kaikoura. Then on February 10, 1923 Jack made the newspapers again. He had been standing on a stack (of hay we think) with a fork in his hand when he was struck by lightning. A sudden storm came from the south-west and there was a huge downpour. But 30 minutes later it had passed and Jack, a single man, was dead. Jack is buried in the small Cust-West Eyreton cemetery with his father, mother and an infant sister. Photo by Frankie Lopez. We love history: http://genealogyinvestigations.co.nz/index.html Only 30 out of 102 people aboard the SS Penguin survived the ferry's tragic sinking on Wellington’s South Coast on February 12, 1909. But there was one more than is usually counted.

With the loss of 72 people, it is still considered one of New Zealand’s worst maritime disasters. Ada Hannam lost her husband Joseph and her four children Ronald, Margaret, George and baby Ruby - she was in fact the only woman to survive the sinking at all. And at the time, she was also a couple of months pregnant. The interisland ferry was on its way to Wellington from Picton when tragedy struck. It had started in fair conditions but by that evening the winds had picked up and visibility had dropped. Captain Francis Naylor was cautious and headed further out to sea hoping for a break in the weather but it turned out to be the worst action he could have taken. It is believed the ship hit Thoms Rock causing a gaping hole through which water began to pour in. Once the cold seawater hit the hot engines, there was a huge steam explosion. Women and children were loaded into lifeboats but the seas were unforgiving, dragging the boats under. Ada got her four children into a lifeboat but as it was lowered it was swamped. Baby Ruby was washed from her arms but she managed to catch hold of the clothing. She couldn’t reach her other three children and struggled to get back into the lifeboat with Ruby. She could see her husband, Joseph, on the deck of the sinking ship. For a while Ada and the others in the life boat were tossed about. Close to dawn they got near the shore but the boat capsized. Ada ended up under the lifeboat with 17-year-old Ellis Matthews. Ironically the capsize saved her life. Ada and Ellis were able to breathe in the trapped air pocket. But they could not get help because, unknown to them, other struggling men had climbed on the overturned lifeboat. Ada knew she had also lost Ruby. But she held her body until the end. Ada calmed Ellis, telling him they would survive. And unable to swim, he clung desperately to her. It took five hours for the lifeboat to drift close enough to land for them to be saved. But it wasn’t the end of the survivors’ problems. They were on a remote coast, in a storm, wet and exhausted. Ada then walked up a steep track to a homestead and the next day went on horseback to Makara. Rescue parties arrived to find bodies strewn along the coast, among them were Ada’s children and husband. Ada Louisa Hannam (nee Thompson, born January 7, 1882 in Picton) had married Joseph William Hannam (who was born in Christchurch) in 1901. Joseph and the four children are all buried in Picton Cemetery. On September 18, 1909 she gave birth to a son, Joseph Walter Hannam. Joseph went on to become a sailor. He died in 1984 - the last survivor of one of New Zealand’s worst disasters. Ada herself died in Onehunga, Auckland in December 11, 1952. They are buried side by side in the Mangere Lawn Cemetery. Most of those who lost their lives were buried at the Karori Cemetery. We love stories: http://genealogyinvestigations.co.nz/index.html The duck that caused a gold rush

It sounds like an urban myth but the tale of Farmer Baker’s wife, who caught a duck for dinner at Kaiwharawhara Stream and on cutting it open, found gold in its gizzard, is a good one. It’s hard to know whether it’s true or not. But George Baker and his wife Susan were certainly living in the area. They had arrived on the Lady Nugent from Exeter in 1841. George was a carpenter and joiner and was employed assembling immigrant cottages brought out from England in sections. He is particularly known, however, for the fact that his property in Karori gave its name to the Baker’s Hill Mining Company, when it became the scene of the Wellington ‘gold rush’. Whether the duck tale is true or not is a matter lost in history. What we do know is that John Brown Reading is the man who started the short-lived gold rush by taking gold into the office of the Wellington Independent newspaper in 1857, causing a great deal of excitement. The bits of gold (and not much of it) were found by prospectors in Karori and Makara. It must have been a fairly wild place back then. It led to others heading into the hills looking for the coveted metal. None of them found much. The little gold there was, was bound up in quartz and hard to extract. But nevertheless gold fields were set up and even today, it’s possible to see the entrance of the Morning Star mine in Zealandia, now more famous for harbouring giant cave weta and glow worms. Alas, no gold of any note was found and all the mining was eventually abandoned. Reading himself was the first born son of a jewellery making family in Birmingham, England. His grandfather had a shop and later so did his father John senior. Reading immigrated to New Zealand aboard the Duke of Roxburgh with his wife Elizabeth Jane Phillips, son and daughter. He was credited with making the first wedding rings in the colony with gold he found in Makara and was the first jeweller in the area. Later he settled in Karori and farmed, was appointed postmaster for Karori, formed a musical society along with the first mayor of Wellington George Hunter and represented Wellington County on the Provincial Council. He and his wife had eight children. John died on November 2, 1876 at the Arthur Street home of his daughter Sarah Jane and her husband William Alfred Waters and was buried at the Bolton Street Cemetery. Reading Street in Karori is named after him. See our work: http://genealogyinvestigations.co.nz/index.html The man who built lighthouses (and roads, bridges, railways and waterworks)

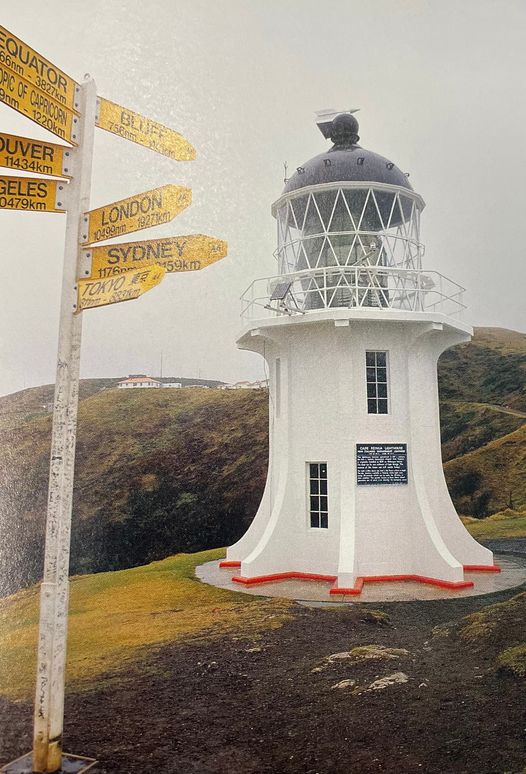

New Zealand has quite a number of beautiful lighthouses. Their solitary perch on remote headlands and often stunning views make them mysterious and romantic places. The man responsible for many was John Blackett. Blackett designed a style of lighthouse just for New Zealand. He was looking for a hardy design, easily built or moved and settled on the now iconic shape of a four, or six-sided lighthouse. He was in particular working toward an inexpensive design that would nonetheless be durable. His innovation was a double wall that could be filled with rubble to help stabilise the lighthouse in often trying conditions. It meant that rather than stone being used in construction, wood could be used which was far less costly. In 1874, with the design ready, a programme of public works was started and 16 manned coastal lighthouses and six manned harbour lights were built. The lighthouse at Timaru, built in 1877, is a perfect example of the wooden design he so often used. The six sided lighthouse at Akaroa is also a good example. The lighthouse at Timaru is called Blackett’s Lighthouse and was moved twice to preserve it; once to Maori Park in 1980 then in 2010 further down the road. Blackett was born in Newcastle upon tyne on October 8, 1818, the son of coal agent John Blackett and Sarah Codlin. He became a pupil with an engineering firm and then a draughtsman with the Great West Steamship Company. On 19 February 1851 he married Mary Chrisp at Kirk Leavington, Yorkshire and they went on to have four children. After their marriage the couple sailed for New Zealand on the Simlah. They landed in New Plymouth but ended up in Nelson where he was appointed the provincial engineer. Lighthouses were not his only project though. Blackett was responsible for the construction and maintenance of roads, bridges, wharves, public buildings and, in 1867, the Nelson city waterworks. His bridge-building won him a silver medal from the commissioners of the New Zealand Exhibition in 1865. He also undertook the exploration necessary to develop the infrastructure needed to exploit the West Coast's gold and coal resources. Blackett became New Zealand’s Marine Engineer in 1871 and then in 1884 Engineer in Chief for the country. Blackett then became Consulting Engineer of the New Zealand Government. In 1890 he returned to England when another man took over the job but returned to New Zealand in 1891 to take up the job again when his replacement died. But Blackett's health was failing and he retired in 1892. He died in Wellington on January 8, 1893 and is buried at Karori Cemetery. His legacy is seen on the many rocky shores of the country. Photo by Grant Sheehan - from Leading Lights by Anna Gibbons. There was no question that Martin James Eyles had a problem with alcohol.

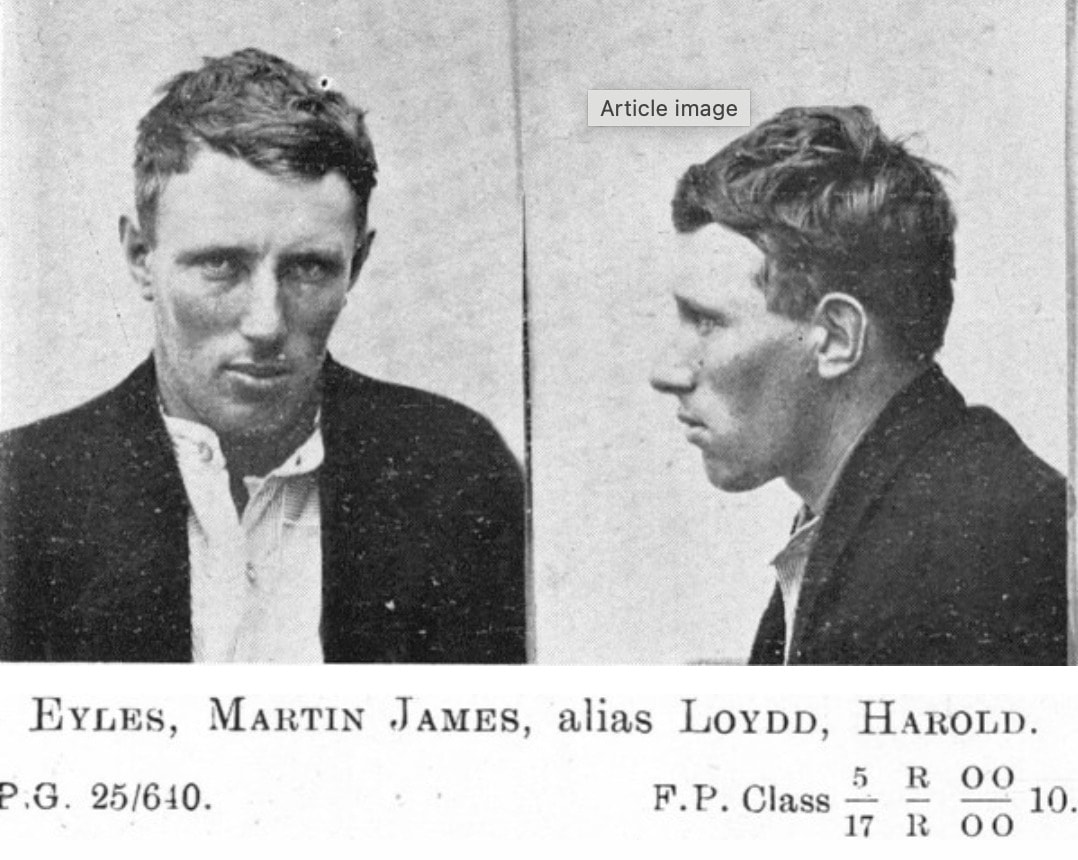

He drank beer before he went to work at Napier’s docks, during meal breaks and after work as well – up to 40 handles a day. And when he didn’t drink beer, he drank his own home-brewed spirits, which his brother, after having a glass, said left him feeling the effects for three days. Eyles claimed his long-term alcohol abuse caused him to go on a shooting spree on a busy holiday afternoon in December 1944 in central Napier, killing two, injuring three and narrowly missing several others. Eyles was born in 1901 in Nelson the third of 6 children of Charles and Louise Eyles. His first brush with the law was a conviction for breaking and entering as a 10-year-old. When he was 12, his father died. Alcohol was clearly a problem for a long time. News stories show that as a 17-year-old he assaulted a 12-year-old girl in a Wellington boarding house while he was drunk. It resulted in the court ordering an alcohol prohibition on him. Eyles received several more convictions up to the age of 25 then appeared to settle down. Then at about 3pm on December 29, 1944, Eyles, then aged 44, walked into one of his local drinking holes, the public bar of the Caledonian Hotel. His friend and bar worker Charles Edmund Swain, 49, greeted Eyles in his usual jovial way, saying: “Good afternoon Mr Eyles.” Eyles pulled a stolen 9mm German pistol from his jacket, pointed it at Swain at close range and pulled the trigger. Swain, who was hit in the shoulder, staggered, and then fell to the floor, dead. The bullet continued its journey after leaving Swain’s shoulder and hit 64-year-old Napier pensioner Thomas Rodgers, shattering his right arm. Eyles waved the gun around, pointing it at other drinkers, who pleaded for him to stop, before he walked out into the hotel’s foyer. There, 83-year-old James Henry Kearny, a retired journalist, on holiday from his home in Karori, Wellington, was resting in one of the chairs. Eyles aimed and fired, hitting Mr Kearney in the shoulder. Eyles then left the hotel, turned left, and randomly fired several shots up Hastings Street, hitting 28-year-old Thelma Allcock in the groin.He then turned to his right and spotted 14-year-old John Barry Bertram Howe, on holiday from Palmerston North. Witnesses described Eyles aiming at Howe, who was riding his bicycle slowly past the hotel, but then lowering the gun, making an adjustment, before taking aim again and shooting the lad through the head, killing him instantly. Detective Sergeant Duncan McKenzie and Detective Andrew Reid, who were nearby, rushed to the scene, only to be shot at by Eyles, one bullet lodging in the car just a few inches from Detective Reid. More police converged on the scene and shots were exchanged. Eyles ran off up Vautier Street with Senior Sergeant Francis Forsythe and two constables in pursuit. Forsythe, who was unarmed, caught up and Eyles surrendered. Eyles, who had also been shot, was taken to hospital. On the way he made two telling statements. He firstly asked how many he had killed, then he said he done it because he had wanted to go to war to get behind a machine gun but they wouldn’t allow him to go. At his trial for the two murders, several witnesses including his brother Henry Charles Eyles, testified about Eyles’ excessive drinking habits. Henry said Eyles drank every day and had done so for 20 years. Eyles claimed he couldn’t remember the shootings. The jury didn’t buy the story and convicted him of both murders. He was sentenced to life in prison. He appealed his conviction saying he had suffered from temporary insanity at the time – his appeal was rejected. It’s not clear when he was released from prison, but by 1963 he was living in New Plymouth and was retired. He died on 19 July 1984 at the age of 83 years. He was cremated. Charles Swain was buried at Park Island Cemetery and John Howe (who was known as Barry) is at Terrace End Cemetery in Palmerston North. James Kearney died five years later, along with his wife and daughter, in a traffic crash near Hastings. All three are buried at Karori Cemetery. Pic: NZ Police Gazette. See more about us: http://genealogyinvestigations.co.nz/index.html |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed