|

His Honour Justice Henry Barnes Gresson placed a little black cap on his head on October 28, 1862, as he sat in the Supreme Court in Dunedin.

It was a fateful moment. Putting on the black cap meant someone was about to be sentenced to death, an odd tradition from England, supposedly from the Irish caip bháis or cap of death, It was historic - the first (reported) murder trial and death sentence passed in Otago. And the man was John Fratson - whose murder of Andrew Wilson, was considered one of the first in the colony. Wilson, who was 25, had left Dunedin to look at some land near the Clutha district - after all, the possibility of land was why so many came to New Zealand. But a short time later when his friend Richard Leary hadn’t heard from him in a while, he went looking. He discovered that Andrew had been seen in the company of a John Fratson who lived in a hut near the river. Richard returned to Dunedin and told the police who went to look for Fratson. They found him trying to make his getaway. He, his wife and two children were on the ship Gothenburg, about to sail for Melbourne. But initially no one knew where Andrew was. The winter of 1862 was unusually severe. And the Molyneaux River was very low. It took some time but Andrew’s body was eventually found with his head smashed in and an axe, found to be Fratson’s, was found with the body. The theory was that Fratson had invited Andrew into his home but then murdered him, No newspaper report mentions why Fratson committed murder but it was clear he and his family - a wife and child - were living in extreme poverty, while Andrew had at least enough wealth to buy some land. The inquest found that Fratson should stand charges and the trial took place quickly. As Fratson’s wife and child sat in the back of the court, the jury took very little time to find him guilty. And Justice Gresson sentenced him to death almost immediately as Fratson sobbed. It must have been quite the moment for Gresson, who had been born on January 31, 1908, in County Meath, Ireland. He became a lawyer there then emigrated with his family in 1854, landing in Nelson and taking an overland track to Canterbury. For a time he was a prosecutor but was appointed a judge in 1857 and became the presiding judge for the South Island. That would have meant the trial of Fratson would likely have been the first murder in the area and the first time Gresson had put on the little black cap and ordered an execution. He later gave up the post of judge when Parliament decided the Minister of Justice could order judges to move to different courts. He turned to farming. Gresson had married Anne Beatty in 1845 and they had two girls and a boy. Gresson died on January 31, 1901 - his birthday - and is buried in the St Barnabas Anglican Cemetery in Canterbury. Fratson however is not listed among those executed in New Zealand after his sentence was commuted to a life sentence in December 1862 following a petition to overturn his death sentence. Photo from The Press.

0 Comments

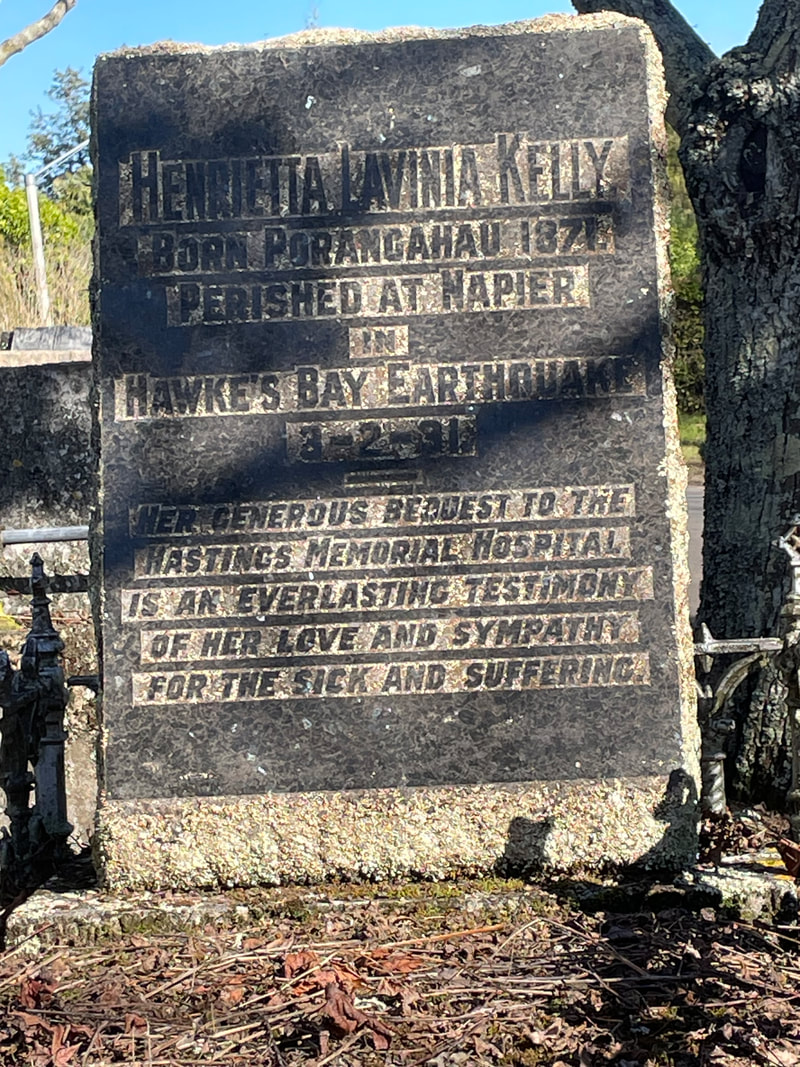

Most people don’t know that the Hastings hospital is actually a war memorial or that one woman’s last wish helped turn it into the hospital it is today.

It was in 2015 that the name Hawkes’ Bay Fallen Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital was restored in full after nearly 100 years. And most people don’t know that a great deal of how the hospital is now was because of a 1931 earthquake victim whose body disappeared after she was last seen in her room by the balcony of Napier’s beautiful Masonic Lodge. It is suspected that there are victims of the 1931 earthquake not properly memorialised and we know there are some whose bodies were not found. One is Henrietta Lavinia Kelly, who had been living in what was called room J on the first floor of the lodge for nearly a year. Her room had a window and a door opening onto the balcony. She had been seen the day of the earthquake but after, with the lodge in ruins and fire rampaging through the middle of Napier, she was never found. But Henrietta’s name should be remembered for what she did after she died. Fundraising for the hospital had started in 1919 and in 1927 the foundation stone was laid. It is inscribed “Hawke’s Bay Fallen Soldiers’ / Memorial Hospital / erected 1927 / by the people of the district / in everlasting remembrance / of our honoured dead/ 1914-1918.” The hospital was opened on Anzac Day 1928. After the 1931 earthquake it became a general hospital. Henrietta was born in around 1871 in Porangahau. Little is known about her early life. But in the 1928 electoral rolls she was living in Knight St, Hastings with Elizabeth Bishop, whose maiden name was Kelly. Elizabeth had been the wife of well known stock agent Thomas Bishop. They had seven sons - only one of whom - Herbert - survived. There are no records of daughters. It was Herbert who tried to find Henrietta in the aftermath of the earthquake. Thomas died in 1888 and left Elizabeth with a small fortune. His will left everything to Elizabeth and after her his children “including daughters.” It’s unclear how Henrietta is related. She might be a daughter whose birth is unregistered. Regardless she had quite the estate and when she died she left her entire estate - £35,000 - bequeathed to the Hastings Fallen Soldiers Memorial Hospital, in Hastings. It amounted to over $1 million then. Her estates were tied up but instructed to be applied to the hospital. “For any such purpose as rebuilding, building additions to the present block, in maintaining the hospital, "or in any other manner for the benefit of the hospital." Because of her the hospital was expanded. And the expanded hospital - taking it from 20 beds to 50 - was opened in 1935 as a general hospital with a maternity and Karitane section attached. Henrietta is buried in the Havelock North Cemetery. It took 10 minutes for the tornado that ripped through the suburb of Frankton in Hamilton to reduce whole streets to rubble, injuring many and killing three.

It had been a rainy day on August 25, 1948, and it was nearly lunchtime when the roaring began. The little town of Frankton Junction was built around the railway station and the industrial commercial area - most men were workers and women were homemakers. In many ways it was a very traditional suburb. None would have expected their world to be turned - quite literally - upside down. The tornado seemed to come from a nearby wooded area and it headed right through the commercial part of Frankton. Within minutes the tornado cut a swath 200m wide through the suburb. One woman was home with her two children, just setting the table for lunch when a huge dark cloud turned day into night. Taking her children she headed to the front door only for the tornado to pick up the entire house, hurl it across the road and drop it. By sheer luck, while the rest of the house was badly damaged, the hallway she and her children were in was intact. Nevertheless the damage was extreme - sheets of corrugated iron were catapulted through houses, 150 houses completely destroyed, along with 50 business premises. Roads became a wilderness of smashed cars, downed telephone poles, twisted wire and furniture flung far afield. In the aftermath another woman showed a newspaper reporter the ruin of her home but for a china cabinet - complete with all its contents completely untouched. As it passed the tornado went through two hospitals, a school grounds and the gas works. In Lake Road, Julius Kitchen and his wife Beatrice were home. The tornado lifted their house and flung it across their section to the railway line beyond. Joseph was knocked unconscious when a door hit him. But Beatrice was found dead beside the railway line with a blow to the head. Their neighbour Mary Jane Dillicar was also killed. Jack Kaa Smith, an engineer’s apprentice died when the garage he was working at was hit. A door was flung on to him and despite getting to hospital he died a short time later. Along with the dead were 80 injured and five needed hospital admission. The damage caused was worth more than £1 million, equivalent to well over $77 million today. Mary Jane Dillicar, nee Tretheway, 76, is buried in Hamilton West cemetery Beatrice Kitchen, 67, 78 Lake Road is in Hamilton East cemetery while Jack Kaa Smith, 15, is in the Ngaruawahia Cemetery. Picture by Noaa Zus. Drowning was once so common it was referred to as “the New Zealand death.”

New Zealand is a skinny country - most of us are only a couple of hours from the sea, a major river or a lake. And for those coming from British and European countries as new immigrants, it was nothing like what they were used to. Here fording a river meant literally walking through one, or riding over it or being ferried in small boats or in carriages prone to tipping over. Official figures show that by 1870, just a few decades after the arrival of European settlers, rivers in particular had been responsible for 1115 recorded drownings. Floods are also the most common natural disasters in the country. Settlers had to deal with thick wilderness, unabridged rivers and almost uncharted coasts. William Curling Young was born on February 21, 1815, to George Frederick Young - a director of the New Zealand company that undertook to bring settlers to New Zealand - and Mary Young nee Abbot. He came to New Zealand in 1843 on the Mary Anne landing in Nelson. William wrote home about the conditions he was living under - a type of tent house - which within a few weeks burned down. But his letters stopped abruptly in August. He had drowned trying to cross the Wairoa River after spending the day looking at sections of land. The river was simply too much for him and he was swept away, ending up in a deep hole. He was also unable to swim. He was buried in the Haven Cemetery in Nelson along with Henry Angelo Bell, his friend who drowned with him. In our cemetery walks we have come across so many headstones that say downed. Like Tom Lester Cooper who drowned in the Whanganui River while swimming in 1909, or Charles A’Court who drowned in a river in Martinborough in 1931 or Rev Samuel Douglas who drowned near Napier in 1893. Even in Deb’s own family the New Zealand death struck. Henry Drinkwater was our very first story - with his wife Sarah. Their 17-year-old son George Drinkwater drowned during a whitebait fishing trip on the Manawatu River near Foxton on September 5, 1901. He and a friend had been in a boat when a rowlock broke and the boat capsized. George tried to swim ashore but his heavy clothes dragged him down and he drowned. The inquest - like so many drowning deaths - found it was accidental. George left not only the rest of his family, but also his twin brother Richard. George is buried at the beautiful Dannevirke Settlers Cemetery not far from his parents’ graves. With special thanks to Sharyn from the Friends of the Settlers Cemetery who helped us put up a plaque for George - who had no marker at all - and for all the work they do maintaining one of the best kept cemeteries we have ever seen. When it comes to inventions, New Zealand is right up there with the rest of the world, the electric fence, the egg beater, bungy jump - all famous ones.

But there is one that you are all using whose inventor’s name is barely remembered. And all because he forgot to get a permanent patent. John Eustace had been born in 1855 in Helston, Cornwall and came to New Zealand on board the Chile in 1862. Not a big lad, he nevertheless had a quick mind despite a lack of formal education. Initially he worked on a cherry farm and then help print and deliver some of the first issues of the Evening Star. At 12 years old he became a blacksmith’s striker then began an apprenticeship as a tinsmith - starting by making tin match boxes. He married Martha Emma Hoskings and they settled down, having three daughters and one son. In 1896 he started his own tinsmith business making kettles, trays and other goods. He was kept busy during the South African War with huge orders. It was during the early 1900s that he was asked to find a way to making paint cans that did not leak. He said it took him a sleepless night trying to figure it out but the next day he created an airtight lever lid for a paint tin. That lid is still in use today. It was so successful that orders began flooding in. not just from New Zealand but all over the world. He took a patent out with some help from painter Robert Fergus Smith for “An invention for hermetically closing tin boxes with th 3 lid without soldering." and began the process of creating a die to mass produce the tins. Except he did not know the patent - an interim one - ran out after six months and from then it was a free for all, with companies all over the world producing their own lids. Smith and Smith, the company that had asked him to make the lid in the first place, promised they would only buy their lids from him and did so while he and his son ran the company. It enabled him to expand the factory and employ many men. At one point he was called an idiot who had lost a fortune - but Eustace replied that ‘Well, I’m happy, I’ve got a good family, I get three feeds a day, I can only wear one suit at a time what would I want with a fortune?’ John died on August 2, 1944 and is buried in Andersons Bay Cemetery in Dunedin. Picture by Sven Brandsma. It’s impossible to predict how someone might die. And every year the way people meet their end gets weirder and weirder.

About 450 people a year die falling out of bed, 150 by falling coconuts and 24 suffered death by champagne corks. Some seem so strange that it’s hard to believe, like the couple trampled by their own camels while the owner of the world’s longest beard tripped over it and broke his neck. Then there are ones that make you roll your eyes. Like the lawyer who tried to demonstrate that a victim could have shot himself by picking up the gun and accidently shooting himself. Or the owner of a wool mill who fell into the machine and was wrapped to death in 800 yards of wool. Yes, some are (tragically) hilarious. How they died is immortalised in the stories. And sometimes this is reflected on their headstones. Mel Blanc - the voice of Porky Pig - says That’s All Folks. William H Hahn Jnr’s reads I told you I was sick. Frances Eileen Thatcher’s reads Damn, it's dark down here. Then there are the types of memorials. Jules Verne has a sculpture of himself climbing out of his grave and Harry Houdini has a bust of his own head. On visits to cemeteries we have found creepy decapitated angels, a gravestone with a window in it (no we don’t know why), crosses made of rusted iron, or slowly eroding wood. Then there are the ones with no headstone at all. It’s not uncommon for those found guilty of murder or have committed suicide not to have a headstone and even to be buried outside the normal bounds of a cemetery. Some however have poetry, wise sayings, words of love and then some have an epitaph that leads to a story. Like the headstone of John Riddall which not only says dearly beloved husband of Ada but also Who met his death whilst skylarking. (so Ada might have been a bit exasperated.) Riddall was 32 when he died - he had been at the Carlton Hotel in Wellington’s Willis Street. He had been sitting on a railing of a balcony on the fourth floor when he overbalanced and fell on April 26, 1919. Riddall had been a grocer’s assistant and relatively new to Wellington. He had been president of the Auckland union of grocers assistants three years before. He is buried in Karori Cemetery. John Martin wanted to not just own a town, but to mark it with his personal history.

As a consequence the town is not just named for him - Martinborough - but is set out in the shape of the Union Jack. And the streets off the central square are named for places he had been like Oxford, Texas, Kansas and Cambridge. John Martin was born on November 11, 1822, in County Londonderry, Ireland to clergyman John Martin and his second wife Sarah. They both died on typhus in 1838, so the 11 Martin children set out for New Zealand on the Lady Nugent landing in Port Nicholson - Wellington - in 1841. As a young man John worked hard as a pick and shovel hand and carted ammunition to militia in the Hutt Valley. On September 14, 1847, he married Marion Baird with whom he had 10 children. He went into partnership with his brother-in-law on some land but the licence for the land was cancelled in 1861 when gold was found on the land. John and his brother-in-law took advantage of it, selling their stock for meat and transporting the gold. John returned to Wellington with a small fortune and bought land in Taranaki St, set up as a merchant and built a residence called Fountain Hall in Ghuznee St. He tried politics but had too much of a temper and failed several times. In 1864 he sold part of his Taranaki St land and bought the 12,698 acre Otaraia station in the Wairarapa. In business he and a partner bought out the New Zealand Steam Navigation Company. He added to his holdings in the Wairarapa by buying another 24,878 acres in the middle of an existing holding, meaning the owner of the surrounding land, Daniel Riddiford, was later forced to buy it - but became John’s enemy. Whatever his business dealings, he was known as a generous host and in 1875 he was responsible for a drinking fountain being put up on Lambton Quay - where the water was mixed with whisky when it opened. It was six metres tall and offered drinking water to anyone. Considered a Wellington landmark for a time, later it was moved and then scrapped when it became too corroded. Later that year, he left for a tour of Europe and America - on the steamer Taranaki, he owned. On his return he was made a justice of the peace and then was called to the Legislative Council where he made no impression at all. Then in 1879 John bought the 33,346 acre Huangarua Estate in the Wairarapa for £85,000 in gold. The land was split into 334 small farms and the township of Waihenga was renamed Martinborough and divided up to be sold. John had a grand vision - laying out the central square with roads radiating from it - but the land auctions were a failure. Nevertheless - over time Martinborough gained a niche reputation and today is known for its vineyards. John also left his mark on Wellington's urban landscape in the form of Martin Square; Marion, Jessie and Espie streets were named after his two youngest daughters and his mother. His wife Marion died on February 11, 1892 and John on May 17 the same year. He is buried in Karori cemetery. St Thomas’s church in Meeanee has survived earthquakes, floods (including the most recent) and disinterest - but now at 137 years old it’s been sold.

The pretty little church has been on Meeanee Road since George Rymer donated the land in 1886. The Anglican church was built for £344 after George wanted it “Given upon trust that the same shall be used as a site for a church for the celebration of divine worship according to the rites and ceremonies of the Church of England in New Zealand.” Designed and built by Frederick de Clere - who built many of New Zealand’s most historic churches - it was opened in 1887. About 150 people attended the opening - more than could easily fit into the little church. In typical Clere style it has a gothic style with a belfry and a natural timber finish inside. The belfry dates from 1911, the church got electricity in 1929 just before the earthquake. The church actually survived well but needed some shoring up. In 1997 the church was saved from sale when the residents rallied around it, but now the church has been sold. Rymer, who was a bit of a daredevil and liked to take a chance, would not be happy that his gift to his community was now gone. Rymer was born in 1844 in Yorkshire. He arrived in New Zealand in 1863 with William Stock and originally was heading for the gold fields. Like so many he found it was not a good way to earn money. Along with Stock he came to Hawke’s Bay and started a stables and early coaching service. He had settled in Meeanee and ran the service between there and Napier, Ahuriri and Awatoto. He was the first to run coaches along the newly opened Taradale Road in 1873. He was also paid by the Government to run the mail through to Puketapu. In 1881 with a road opened between Napier and Kuripapango (up the Napier//Taihape Road) Rymer began a service. Kuripapango was being touted as a resort for its fresh air. He also won the royal mail warrant for the route. But he had competition from Alexander Macdonald and the two companies’ coaches would race each other for business. It got so intense that people would gather to watch and bets were made. It led to quite a few accidents. Rymer married Annie Harvey in 1868 and they had five children. He retired from his business in 1902 selling it to the Hawke’s Bay Motor Company for £10,000 - well over a million now. He went on to serve on the Hawke’s Bay County Council for three terms. Rymer died on April 7, 1917 at his Marine Parade home and is buried in the Taradale Cemetery. Rymer St in Meeanee is named after him. Like any hotel, Napier’s Masonic Hotel has seen some things.

Earthquake, fire, a visit from the Queen, Mark Twain and ballerina Anna Pavlova, deaths - which led to ghosts apparently. The big art deco hotel is an anchor stone of Napier’s history, it's been there so long it wouldn’t be Napier without it. It was Joseph Gill who owned the first Masonic Hotel on the foreshore site, opening on September 14, 1861. It was smaller than it is now. It was expanded to cover the complete section in 1875 by which time it was owned by Alexander Dalziell. But on May 23,1896, fire destroyed the hotel. There was some controversy as the fire bell was not rung until 15 minutes after the fire started even though smoke was throughout the hotel. Within a month, plans were underway to rebuild the Masonic, with three storeys with the stables alongside. Another two storeys were later added. It was huge and one of the most up to date hotels in the country but it all was for nothing when the 1931 earthquake hit and the hotel was again reduced to rubble, mainly from the fire that ravaged through Napier after. For a while it was replaced with a temporary corrugated iron building. Then the building we all now know was built. Architect William John Prowse (or Prouse) designed it as a simple hotel but with the elegant upper storey pergola and the big Masonic sign in art deco design. The hotel is now considered one of the jewels in Napier’s Art Deco crown. Ghostly occurrences have been reported many times. Strange lights, music and cold spots. Like any hotel there have been deaths on the premises. Two are supposed to have left the hotel haunted - a chef who died in a bathtub and a guest who would stay for weeks at a time in the same room every year. The hotel has also had its fair share of royal visitors to its royal suite. Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip and the Duke and Duchess of York (who became King George and Queen Elizabeth, the queen mother). Joseph Gill was born in 1826, in Cornwall, England and came to New Zealand on the Sanford in 1856. He married Ellen Palmer in 1859 and they had seven children. He went on to run several other hotels in Hawke’s Bay. Joseph died on June 21, 1870 and is buried in the Old Napier Cemetery along with three of his children who died in infancy. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed