|

The grave of Phllis Avis Symons (centre with no headstone) at Karori Cemetery Grave Story #3

Everyone knows that you toot in the Mount Victoria Tunnel in Wellington but not everyone knows it’s supposed to be because of a ghost. Since it’s Halloween we thought we would share with you the ghostly story of murdered 17-year-old Wellington girl Phillis Avis Symons. Phillis was killed by her lover, George Erroll Coats. A widower with six children already, and he did not want another. So when Phillis told him she was pregnant he did not want to keep her around anymore. Phillis was an unsophisticated girl, and her parents had not agreed with her liaison with Coats so she had ended up living with him in a ramshackle rooming house in Adelaide Road. In June 1931 she went missing. Work on the then-under-construction Mount Victoria Tunnel had to be halted as a massive search began for her. More than 100 workers shifted an estimated 2000 tonnes of rubble in the search, which ended when her body was found in the spoil excavated from the tunnel. Phillis was found face down wearing a scarf. The case horrified Wellington. A pathologist said he believed she was made to kneel before being hit over the head with a spade then tipped into the hole made for her. But worse was to come. The pathologist believed also that she - and her unborn child - were still alive at the time and only died when the earth was thrown over the top of her. Coats had been a relief worker at the works site but had lost his job, meaning he was familiar with the area. Coats’ trial was a sensation. People queued to get into the Supreme Court to hear it. There was even a scramble for seats. He was found guilty and hanged at the Mt Crawford Prison on December 17, 1931. Phillis and her baby rest in an unmarked grave in Karori Cemetery. Coats too is in an unmarked grave in Karori sharing the grave with his wife Constance and their two-month-old baby Pat who died five days apart in April 1930 - a year before Phillis' murder. While Phillis did not actually die in the tunnel it was believed the tooting started as a mark of respect to her. Nearly 90 years after her death, Phillis is remembered, if only in the loud honking of horns by passing cars. Happy Halloween and don't forget to toot for the ghost of Phillis!

1 Comment

For eight days in 1848 Wellington shook. Grave Story #2.

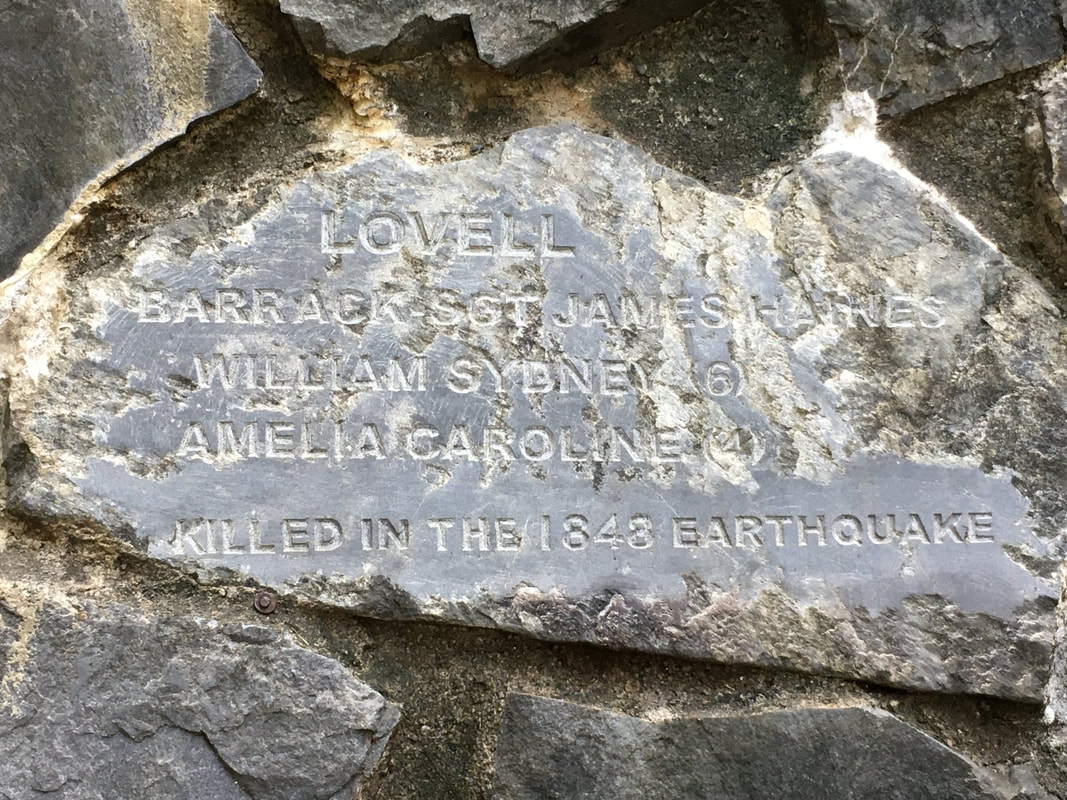

For the new European settlers the days of earthquakes were a nasty shock. Many of them had never been through one, or even heard of them. At the end of it, 80 buildings were destroyed, and three people were dead. Barrack Sergeant James Harris Lovell was walking along Farish St with his daughter Amelia, 4 and son William. 6 when bricks fell and crushed them during an aftershock. They were immediately dug out but Amelia had already died while William and his father died in hospital. They were the first Caucasian people killed by earthquake in New Zealand. It was one of the biggest earthquakes experienced, reckoned as a 7.5 on the Richter scale - but back then considered a 10 on the old scale used, the most severe of magnitudes and originated in Marlborough. He and his children are buried in the Bolton Street Cemetery where there is just a memorial stone on the wall. The earthquakes, which started on October 16, preceded by a severe storm and continued for eight days, were a revelation to settlers. When the first one struck many rushed about, not knowing what was going on or how to respond. The Wellington Independent newspaper wrote “about half past one o’clock am this morning (Monday), a distant hollow roar was heard, the counsd travelling at the most rapid rate, and almost instantaneously, in the course of a few seconds of time, the whole town was labouring from the most severe shock of an earthquake ever experienced by the white residents, or remembered by the Maori.” As they continued it was devastating for Wellington. A great many building were built of brick and stone, just as they were in their home countries. It was quickly discovered that bricks and stones came crashing down. It would lead to a revolution in the building of wooden buildings in Wellington as wooden building had fared better. Commercial buildings, barracks, the jail and the hospital were damaged and patients were taken to Government House for treatment. The day after the largest of the shakes the tide rose, overflowing what was then Lambton Quay. In fear people sought to flee Wellington, some opting to try for Australia. Many boarded the barque Subraon to sail for Sydney but there was no escape. The barque ran ashore at the Wellington Heads where she was wrecked. All the passengers were saved but found themselves back in the city they had tried to escape. Mr Justice Chapman wrote of a strange illumination in the sky following the biggest shake, a weird lurid light that lit up the night sky while Mary Waring Taylor, writing to her good friend, author Charlotte Bronte said it had a great impact on immigration. Henry Drinkwater, bottom left. Henry Drinkwater wasn’t famous, wealthy or notorious but he still had one hell of a story.

Deb went looking for an ancestor. Ever wondered if you are related to royalty? What about a notorious pirate? Or even worse, a politician? Most people have wondered a time or two about previous generations. With lockdown this year Mother’s Day was harder than normal. Unless you were very organised or could send something online, there was nowhere to go for a pressie. So I got thinking, what if I played to my strengths and sent Mum a story? I started looking for a particular relative who had always interested me and ended up with another, Henry Drinkwater. Henry was born in 1849 in England and with his mother, brother and sister ended up in a poorhouse. Poorhouses were generally considered places of disease and poverty, conditions were sometimes dreadful and usually all were put to work. He lost his whole family soon after but was lucky enough to end up in an orphanage where he received an education. He met Sarah Franklin in 1974 and shortly after they married they came with Sarah’s parents to New Zealand - back then a three month trip at sea - and ended up in Hawke’s Bay. After working there, he and Sarah went to what was then a small town - Dannevirke. He started his own carrying company and helped found the volunteer fire brigade Henry is a good example of how our ancestors shape our lives. He started with literally nothing and worked hard all his life. He and Sarah’s children - 15 of them - spread out around the country. His son Robert was my great grandfather, one of those who stayed in Dannevirke. We found a picture of the ship Henry and Sarah sailed in and then I was delighted to find a picture of Henry - along with the rest of those who founded the fire brigade. He looks very official in his uniform. All of this was done online - there are a vast number of resources available for people looking for their past relatives. There was even an obituary in a local paper when he died aged 61 in 1910. Sarah died 10 years later. On a recent trip (out of lockdown!) I had the pleasure of finding Henry and Sarah’s graves in the beautifully maintained Dannevirke’s Settler’s Cemetery. Here’s a tip - most councils have a search system to allow you to search by name for someone which gives you a plot number. They also have maps of their cemeteries, allowing you to find grave sites quickly, most can be downloaded from their websites. Last week Fran was interviewed for a community radio show called the Final Curtain, about the work that we do at Genealogy Investigations. You can listen to the podcast of the show here: The Final Curtain.

Archibald Milne’s unsolved murder - Grave Story #1

It was an argument with his father that caused Archibald Milne to sail to the other side of the world, arriving in Wellington aboard the Lady Nugent on March 17, 1841. Within nine months he would be dead. His death remains one of New Zealand’s earliest unsolved murders and sparked conflict between Māori and settlers. Archibald and his fellow “intermediate-class” passengers were filled with optimism on their journey to New Zealand, but optimism soon turned to despair when they found the land they had been promised and purchased from the New Zealand Company was not forthcoming. In a letter dated 26 August 1841 to Colonel William Wakefield, the New Zealand Company’s principal agent, Archibald and other settlers complained about the lack of surveyed sections in Wellington available to them. Archibald, who was a magistrate in England, was unhappy with Wellington and had planned to return to his homeland. He never made the journey. On Wednesday, 15 December 1841, Archibald’s body was found partly submerged on the beach just over a kilometre south of Petone. He was 35 years old. He had been beaten around the head and face and his skull had been fractured. He was partly-clothed; his blue jacket, cap, white moleskin trousers, one sock and his watch were missing. There were two suspects, one was Archibald’s friend John Osborne, with whom he had argued in the days before the murder, and the other a young Maori man named Awaho. At the inquest into Archibald’s death, several witnesses described seeing a Maori man following Archibald along the beach shortly before his death. At the inquest they identified Awaho as the man, however, Awaho testified that he had not been on the beach and they were mistaken. The Coroner gave the jury a stern warning about the need to avoid bringing Maori and settlers into “collision by an imprudent or injudicious act” as the result might be “melancholy and disastrous”. The jury found a verdict of “wilful murder against some person or persons unknown”. With the case unsolved, the chief police magistrate, Michael Murphy, offered a reward of fifty pounds for information that would lead to the conviction of the guilty party. No one came forward. The case created some disagreement among the settlers, some of who felt police had failed in their investigation of the case and failed to charge Awaho with the murders, while others felt that Awaho was implicated simply because he was Maori. In February 1842, there appeared to be a breakthrough in the case. Osborne was arrested as he left Wellington for Nelson and charged with the theft of a coat and tablecloth belonging to Archibald. Osborne came up for trial on the theft charges but was acquitted as there was no proof that he had actually stolen the items. And there the case remained until December 1843 when Awaho became the prime suspect in the theft of a gown and cape, two nightgowns, a waist coat and two silk handkerchiefs the property of Emma Stutfield. Efforts to arrest Awaho resulted in conflict between police, soldiers and Maori. The New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator reported that when the clothes take from Mrs Stutfield were retrieved from a box belonging to Awaho, Archibald’s stolen clothing was also seen in the box, but when it was searched again several days later by police and Archibald’s cousin James Smith the clothing was not found. Awaho was found guilty of the theft of Mrs Stutfield’s property and sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. Archibald’s murder gradually faded from memory, until 2 January 1845 when Awaho tragically committed suicide. Shortly before, Awaho had again been charged with theft, this time of “some biscuits”. Writing two years later, Edmund Halswell, the Magistrate who had sentenced Awaho to imprisonment for the theft of Mrs Stutfield’s clothing, stated Awaho had been banished from Ngauranga and Petone by his relatives because of those thefts and had found refuge at Pipitea Pa. Halswell went on to say that Awaho had shot himself through the heart as he was “ashamed” of being charged with another theft. Archibald was buried in the Public Cemetery in Wellington (now Bolton Street Memorial Park) on 17 December 1841. He has no headstone. The records do not state where Awaho was interred. The Milne family were dogged by tragedy. Archibald, who reached the age of 35 was one of the longest-lived of his at least 10 siblings. Check below to find out more about the Milne family and find out if you might be related to Archibald and others from his family who came to New Zealand. Archibald Milne and his twin brother John were born on 17 August 1807 in Kirktown of Alvah in Banffshire, Scotland to John Milne and Jean, whose maiden name was also Milne. The Milnes were a noted family and considered British gentry. The Milne family had owned and operated the large Mill of Boyndie for more than 200 years. Many of Archibald’s brothers died very young:

None of Archibald’s siblings came to New Zealand, but his cousin James Smith was one of Wellington’s earliest settlers, having arrived in 1840 aboard the sailing ship Coromandel. James had a successful career as an auctioneer and general storekeeper in Wellington. He married his business partner’s sister Marian Rollason Wallace in 1846 and had six children. Marian died in 1858 in England and James died in 1876 aged 58 and is buried in Bolton Street Memorial Cemetery. Their children and grandchildren, many of whom lived in Wellington and the Wairarapa, were:

Death. Nobody likes to think about their own demise, but it is 100 percent guaranteed to happen to you one day and unfortunately for some it happens sooner than they expected. One of our recent cases involved a young woman who left her home one wintery afternoon to run some errands. She never made it back, instead she was fatally injured in a car accident. She had no will, and why would she? She was young, had no husband or children, and had not expected to die that afternoon. This young lady, let’s call her Amanda, had, however, planned for her future children, having taken out a life insurance policy some time earlier. Whoever it was that tidied up her affairs after her death must not have known that she had taken out life insurance, and why would they? She had not left a will. By the time Amanda’s file landed on our desk, she had been dead for several years and the money in her insurance policy was at risk of being given to the State because no one could find who her next of kin were. At this point some explanation is needed of what happens to your estate (your stuff and money) if you die without a will. There is quite a complex formula for who gets what, which I will simplify for the sake of brevity (and sanity). Basically, your first heir is your spouse, then your children. If you have no children, then your parents share your estate with your spouse. If you have no living parents, spouse or children, then it gets a little more complex. Your heirs will then be your brothers and sisters and their children, but if you have no living siblings and there are no nieces and nephews then your estate goes to your grandparents and your parents’ brothers and sisters and if they are not living, then to their children. Confusing huh? The simplest way to avoid this situation for your heirs is to make a will, and once you have done this, keep it up to date. There’s no point, for example, leaving your prized gold leaf tea set to your Aunty Betty if she died 10 years before you. It is also a good idea to keep addresses and contact details for those who are named as beneficiaries in your will, written down and stored with your important papers. Having a will helps your executors and your family know what your wishes are and usually helps avoid arguments over who gets what. While dying is probably going to be tough for you, it might be even tougher for those who you leave behind if you have not left them with instructions about what you would like to happen to your money and personal items after you have gone.

What happened in Amanda's case... Sadly, Amanda’s death barely made the news, and unfortunately the police officers who had dealt with the case could no longer remember, who from her family they had been in touch with. Both of Amanda’s parents had died, but fortunately, from their headstone, we found out that Amanda had two siblings. Unfortunately, we only had their first names. New Zealand’s privacy laws are quite strict and finding information about people other than yourself is pretty much impossible if you don’t know where to look. The situation with Amanda’s estate is surprisingly common, and if you take a look at the IRD’s money owed website you will see a large amount of money which has come from deceased estates. In many of these the heirs have not been able to be located and in some cases the rightful heirs have no idea that they are even related to the deceased person and that they are entitled to benefit from the estate. Fortunately for Amanda’s two siblings we managed to locate contact details for them. Both were married and living overseas, and each received half of Amanda’s life insurance policy, but not without a lot of thinking outside the box and effort on the part of the team at GI. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed