|

Like warriors the world over, they charged into battle on their trusty steeds. Only in this case, the steed was a bicycle, a BSA Mark IV to be precise.

It wasn’t the usual steed or even the usual type of vehicle for troops. But for the 300 odd men of the ANZAC Corps cyclist battalion in World War One, it was their transport over the muddy and treacherous roads of the Western Front. The sturdy bikes carried not only their rider, in full uniform, with a gas mask but also equipment. The corps were created the year before and were intended as light infantry, able to carry out reconnaissance, but the reality of trench warfare made that of little use. Instead they controlled traffic, laid telephone cables and repaired trenches in preparation for the battle. At one point it was estimated they had dug 37km of trenches - all at night. On June 7, 1917, at the Battle of Messines they rode into action. On the day the battle was to begin they were to build a track to allow traditionally mounted troops to ride through wire, shell holes and waterways. It had to be done in less than four hours. So in the middle of the night on June 7, they cycled 13km wearing gas masks before leaving their bikes and heading to the front lines. As the battle began, so did their work on the track, across No Man’s Land and through the German trenches. It was extremely dangerous and they did it under fire. Four Anzac cyclists were killed and 22 others wounded but they completed the track. Later that same year they laid vital telephone cables before the attack on Passchendaele. By the end of the war 708 men had served in the New Zealand section of the Cyclist Corps, of whom 59 had been killed and 259 wounded (51 more than once). Nearly all of those men are buried in France or Belgium. Two on the Roll of Honour made it back to New Zealand but died of their injuries. One was Dudley Edward Harrison, 23, who is buried in Dorie Cemetery (he had been shot in the head) in Rakaia. The other is Edward Wawman, 25, who is buried in the Te Aroha Cemetery in the Waikato.

0 Comments

By the time she died, aged 80, in 1901, Mary Ann Muller had the satisfaction of seeing women win the right to vote in 1893, something she had been working for in secret for decades.

Few would know her real name now, but she was - known by her pen name Femina - New Zealand’s first public suffragist. Born in London on 22 September 1820, Mary was the daughter of James Norris (who used the surname Wilson) and Mary Croft. They had married in secret in 1814, but the marriage did not last - in fact James took off and married again bigamously - and Mary knew him as a godfather until he died when she was 18. It can’t have made her think fondly of men. Mary herself married chemist James Whitney Griffiths in 1841 and had two sons and a daughter. But, possibly because of Griffiths’ cruelty, the marriage failed and in 1850 she embarked on the Pekin to come to New Zealand. She was listed as a widow but since Griffiths is not recorded as dying until 1855, this may have been a fiction necessary for her to escape. She met Stephen Lunn Muller, a surgeon, on the ship who would go on to be her second husband and in 1857 they settled in Blenheim. Mary - probably because of her own experiences - had strong opinions about women losing all rights to own and control property and that they were not able to vote. Behind her husband’s back she began to write - under the pen name Femina - articles on women’s rights which were published in the Nelson Examiner. Her husband did not agree with her views and even when those who did know urged her to come forward, she did not. In 1869 her most famous work was published An appeal to the men of New Zealand. It argued that women needed the vote to be allowed to contribute fully in the development of the nation. She wanted the repeal of discriminatory legislation and asked men - those in Parliament - to take up the cause. The work of our other great suffragists like Kate Shepherd is built on the back of Mary's. In 1893 New Zealand women won the right to vote - the first in the world. And Mary for the first time registered as an elector. There is no information on whether she voted, but we like to think Mary took advantage of it at that very first election in November 1893. It was seven years after her husband’s death in 1898 that she was revealed as the voice behind Femina. Mary died in Blenheim on July 18, 1901 and is buried in Omaka Cemetery. Taranaki in the 1890s was gripped by fear. There was, incredibly, a highwayman robbing people.

“Stand and deliver” was a phrase taken straight from penny dreadful novels and highwaymen were the stuff of serialised romantic novels. Except when you are confronted by one. As it turned out, this one was a teenager. Robert Herman Wallath was born at sea on about July 18, 1874 on the ship Herschel off the coast of Cape of Good Hope off the southern tip of Africa to Hermann Christoph Wallath and his wife Catherine. The German couple had emigrated to Australia and from there to New Plymouth, becoming farmers in Westown. A road there is named after the family. Robert was an intelligent well-built lad who became a sub-editor of a locally published journal, a carpenter and a member of the Taranaki Rifle Volunteers. His first crime was to waylay Henry Jordan while riding home on April 18, 1892. The highwayman was dressed in a mounted infantry style uniform with a type of mask around his face. While Mr Jordan had initially treated it as a bit of a joke, over the next 15 months the crimes continued, burglaries, robberies of hotels and the Omata tollgate leaving residents in terror. Then on July 20, 1893 the highwayman tried to hold up the Criterion Hotel - for the second time. He presented a loaded pistol and demanded money. This time there was a fight and Wallath’s pistol went off injuring Harold Thomson, law clerk and the son of the local police inspector. By the time it was over, Wallath had been captured. After a brief bit of excitement in August 1893, when he escaped and was recaptured, he was brought to trial at the Supreme Court on charges of wounding with intent to kill. A series of other charges of burglary followed along with one of escaping. He was found guilty and sentenced to eight years in Mt Eden prison. Police had found he would hide clothes nearby and change into them to prevent being caught. A search of his room at his home, which he had kept locked for two years, found goods stolen from the various places he had robbed. He was indeed inspired by the novels about the exploits of characters like Dick Turpin. He did not serve his whole sentence after a group of citizens, concerned about his youth, lobbied for his release. He returned to New Plymouth and later married Ada Clara West and had two sons and two daughters. His life of crime was then behind him, he became a well-respected tradesman. Ironically, once he retired he wrote a book entitled A highwayman with a Mission under a pseudonym in which he looked at the struggle between good and evil that had tormented him. He died on July 24, 1960 and is buried along with his wife in the Hurdon cemetery in New Plymouth. The myth was that New Zealand had no native flowers. Where that story had come from no one can tell, especially since it is quite obviously not true.

One woman set out to disprove it and she did so with a series of stunningly beautiful botanical prints showcasing New Zealand natives the way no one had before. Sarah Ann Featon was born on July 14, 1847, in Market Drayton, Shropshire, England, to Henry William Porter and Sarah Hannah Porter. Henry ran a series of pubs (his father had been a wine merchant). There is not much information about her early life. Sarah Ann Porter arrived in Auckland on January 29, 1870 on the maiden voyage of the sailing ship City of Auckland and married Edward Featon in St Paul's Church, Auckland. Edward had come to New Zealand with his parents in 1860. He was employed as a navigational instrument maker and optician and joined the Onehunga Naval Volunteers in 1863 and then the Auckland Naval Volunteers. He later received the New Zealand War Medal The couple had a daughter, Sarah Ann, who died as an infant and son Edward Victor who was born in 1872. It’s not known how she became interested in art but during the 1870s and 80s she and husband Edward undertook a series of paintings of native flowers and plants that were gathered into a book featuring 40 of Sarah’s watercolours with words by Edward. Entitled The Art Album of New Zealand Flora, it was the first full-colour art book published in New Zealand and turned out to be a bestseller. It also contained mātauranga (Māori knowledge) of the plants. Her work was so well regarded that a copy was presented to Queen Victoria. Edward died on June 22, 1909 at their Gisborne home and by 1919 Sarah was in desperate need of money and sold her whole collection to the Dominion Museum (now Te Papa) for £150, where it still is today. She died aged 79 on April 28, 1927 and is buried in Makaraka Cemetery in Gisborne. Last year several of her collection were chosen as a new stamp release by New Zealand Post. The photos are taken from the collection held by Te Papa. Richard Henry was a persistent man. He wanted to save the kākāpō and he wasn’t going to let anything stand in his way.

Determinedly, he and an assistant rowed cages full of the fluffy green flightless birds to Fiordland’s Resolution Island in 1894, creating the world’s first island bird sanctuary. The birds were already in peril in the 1800’s. Stoats were their enemy and there was a push to find a way to help the birds. Richard Treacy Henry was born on June 4, 1845, in County Kildare in Ireland, the fourth of seven children of John Stephenson Henry and his wife Sarah Anna. Initially the family came out to Australia, Richard’s mother and baby brother died on the journey. The rest of the family moved to Melbourne eventually settling in the Warrnambool district of western Victoria. Richard spent a lot of time with local Aboriginals, observing the seasons and wildlife and was fascinated. After a failed sawmill business with his father, and a marriage to Isabella Curran, Richard packed up and headed to New Zealand by himself in 1874. Self-reliant, he travelled, taking jobs where he could before settling at the southern end of Lake Te Anau where he became known as a bush guide. Any time to himself was spent observing birds. He correctly attributed a loud booming sound heard locally to the kākāpō and, noting that its numbers, along with those of the weka, kiwi, teal and whio, declined after the introduction of weasels, stoats and ferrets and he predicted the kākāpō 's extinction. He became friends with other conservationists and they began to promote the idea of Resolution Island as a safe haven for birds away from the dangers of the mainland. Nothing initially came of it and Richard became depressed, moving to Auckland but then he was appointed the curator and caretaker on the island. He and an assistant Andrew Burt sorted out accommodation on the island then undertook the laborious task of rowing more than 700 kākāpō to the island. He captured 100 or so more, shipping them to other sanctuaries. After four years of determined effort, he settled into the island to watch over the birds. But the same problem that existed on the mainland, had come to the island, stoats. In 1908 he was transferred to Kapiti Island where he continued to work until 1911. He retired to Katikati in 1912, moving to Helensville in 1922. He died in the Auckland Mental Hospital at Avondale on 13 November 1929. Only one person attended his funeral. Despite the fact the experiment on Resolution Island didn’t work he paved the way for what are now other successful island sanctuaries in New Zealand. The writings he had done during his years observing birds also laid the foundations for further efforts to save the kākāpō in the 1970’s. He is buried at Hillsborough Cemetery in Auckland. Picture from the Te Papa Collection. Famous bicycle maker Nicholas Oates has the singular honour of being the first person in New Zealand to be brought before a court for speeding, but in a car.

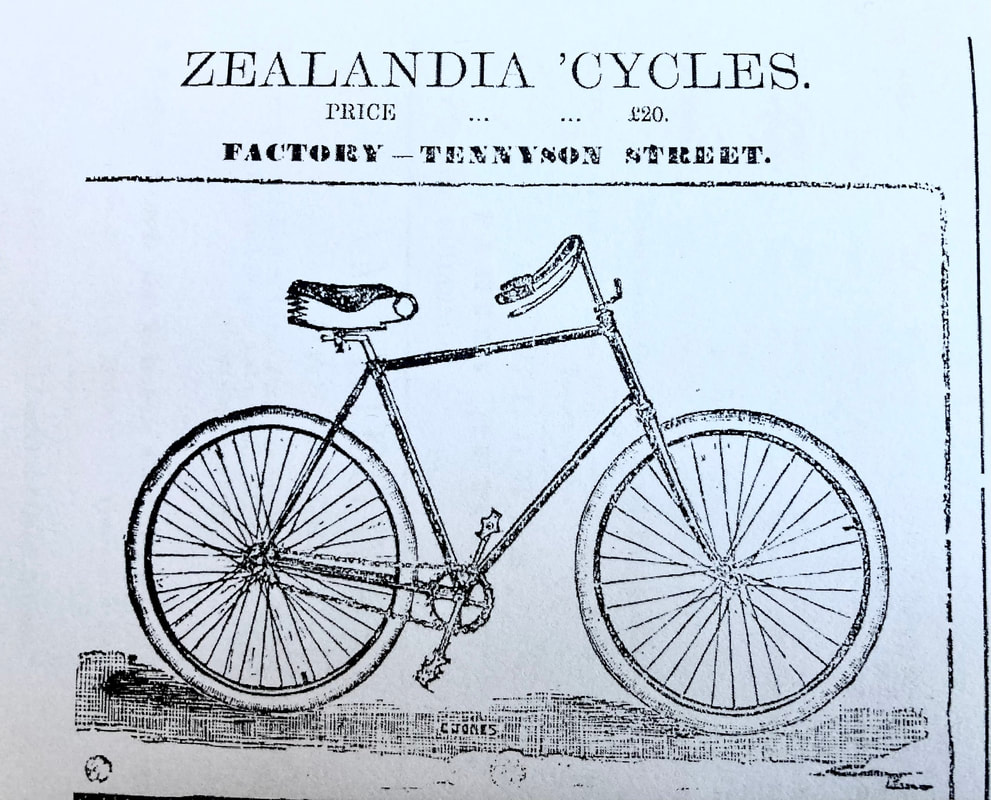

At the time, in 1901, there were only seven cars in the whole of Canterbury. George Gould’s groom, horse and carriage were on Lincoln Road in Christchurch outside the hospital on May 1, 1901, when a car went past at high speed. The horse became frightened and bolted. The groom had trouble regaining control as the car went past. Witnesses swore the car was going at least 10 miles an hour (16kmh) and that only the quick actions of the groom prevented a serious accident. The car was driven by bicycle factory owner Nicholas Oates. He was charged with driving a motor car within the city going a speed greater than four miles an hour. He told a Christchurch magistrate that his car had two gears and that he could go between 6-14 miles an hour. He had the high gear on as he came into town but changed to the lower gear as he took the corner of Lincoln Road and Tuam Street. He saw the horses and sped up a little to pass them, pulling into Antigua Street but claimed he was was not going more than seven miles an hour. It didn’t appear to help, he was fined 20 shillings. It wasn’t the first time a vehicle had gotten Oates into trouble. In 1888, he was fined for riding his bicycle on the footpath. Not content with the criminal court, Gould sued Oates claiming £23 for damages to the carriage and injuries to the groom and horse. Oates disputed it but ended up being ordered to pay £15 in damages. Oates was in business with Alexander Lowry. They owned Zealandia Cycle Works, at the time the largest bicycle factory in Australasia. He was the first person to import a small car in the South Island after he had seen one at the Paris Exhibition in 1899. He was also the first person to construct a penny farthing bicycle in New Zealand. Charles Nicholas Oates had been born in about 1853 in Cornwall, England the son of Nicholas and Mary. He married Catherine in 1875 and they came to New Zealand, shortly after settling in Christchurch. They had been happy for a while, having 10 children, of which six survived. But in 1904 Catherine asked the Supreme Court for a judicial separation. She described a relationship that had been steadily breaking down, in part because of Oates’ friendships with other women. He had also spent months overseas away from his family. The judge granted the separation. Oates died on April 3, 1938 aged 85. He is buried in Bromley Cemetery, Christchurch. With a name like Disappointment Island, there has to be a story there right?

Well there is, but it's not really about the name or how it got it, but rather about horror shipwrecks, starvation and eventual rescue. Little Disappointment Island is one of seven uninhabited islands in the Auckland Islands chain, 475 km south of the South Island. Now its claim to fame is as the home to nearly the entire world’s population of white capped albatrosses. But it used to be known for the number of shipwrecks and stranded crews there. The most famous is the General Grant - which wrecked on one of the other small islands and the remaining crew made for Disappointment (see how nicely that works) Island. The wreck left 15 people alive out of 58 passengers and 25 crew, along with a cargo of wool, skins, 2,576 ounces of gold, and 9 tons of zinc spelter ballast. The fortune in gold has led to numerous attempts to find the ship, with no luck to date. But well after the General Grant, in 1907, the four-masted steel barque Dundonald, sailing out of Sydney, heading to Britain with a cargo of wheat, became another disappointment. The ship was forced onto rocks during a squall on the west coast of Disappointment Island and sank. Seventeen of the 28 crew managed to escape and reach shore although one man, Walter Low, slipped off the cliff and fell into the sea while another died of exposure 18 days later. For seven months the rest survived - although barely. They ate raw mollymawks (a type of albatross) until their matches dried enough to start a fire that they kept going. For shelter they dug into the ground and constructed a sod roof. They knew there was a food depot about 8km away on one of the bigger islands and built a small boat. The first three men managed to make it to the island but could not find the food. The little boat was smashed so another was built and a further attempt was made. Four men managed to get to the island and make their way to Port Ross, harbour on the island where they found the food and another boat. The rest of the crew were ferried from Disappointment Island to Port Ross where they were finally rescued in November that year by the scientific vessel Hinemoa captained by John Bollons. Although he found them on his trip out to the Campbell Islands, he did not actually rescue them until his trip home. On board the Hinemoa was Edward Kidson, the son of Charles and Christiana Kidson in Bilston, Staffordshire, England coming to New Zealand when he was three. Kidson became a meteorologist and travelled extensively carrying out surveys. During the First World War he served in the Royal Engineers developing a forecasting service for artillery. It was during a survey trip that he was on the Hinemoa. He wrote a diary that his wife Isabel later published. Kidson said all on the Hinemoa were amazed to come across the survivors of the Dundonald. They told him that they had tied messages to albatrosses in a vain hope of rescue. In 1927 Kidson was recruited to the New Zealand Meteorological service where he was director for 12 years. Kidson died suddenly on June 12, 1939 and is buried in Karori Cemetery. There is a small cemetery on Auckland Island where Jabaz Peters - the first mate of the Dundonald was buried. With him are a small number of burials from a short lived settlement . Henry Harwood, who opened up tracts of land around the Golden Bay area, is known for giving his name to the deepest vertical shaft in New Zealand - Harwoods Hole.

He and John Horton and Thomas Manson opened up the Canaan Downs area, joining the Tasman and Golden Bay area and found the hole. It was not immediately explored. But later was found to be over 357 metres or 1230 ft deep. Like all things mysterious, people wanted to have a look. Geological history suggests it was formed from stream runoff - basically the water flowed down a valley to the lowest point and formed the hole. Subsequently the stream has changed course and water no longer runs into the hole, rather it trickles in, creating calcite deposits. In it is the beautiful Starlight cave, discovered when explorers were looking for the subterranean stream in the hole. Harwood’s family was some of the earliest pioneers of the area and descendants still live and farm there. It was in 1960 during the first real exploration of the hole that tragedy struck. Peter Lambert was part of the team completing the first descent in 1958/59. Auckland engineer and keen caver Richard Scott, along with a team - including Peter Lambert - created a rope and engineer method to lower people into Harwoods Hole. The seven-strong team set up the engine and also sent down a telephone wire for communication. The first to be lowered was Dave Kershaw who finally radioed to the top that he had reached the bottom. The next day three more of the team headed down, Lambert was with them. They were able to explore some of the extraordinary structures in the hole before they headed out. The next year Lambert signed up 21 other keen explorers for another look. They successfully discovered the hole was connected to the Starlight cave discovered nearby. But tragedy hit as Lambert was being winched back up. With no warning huge chunks of rock came away, smashing into Lambert. He was winched out but died before any help could arrive. A memorial to him was built at the bottom of Harwoods Hole and his hard hat placed on top. Henry Harwood died on April 22, 1927 and is buried in Rototai Cemetery in Takaka. Normally we start these stories knowing just where someone’s grave is. But in the case of Belle Gunness, it's not even sure what happened to one of the first American female serial killers…..except an unsettled suspicion she could have escaped death to come to New Zealand.

In 1908, when the full horror of what Gunness had been up to came to light, it was initially believed she had burned to death. But later, with scanty proof, speculation turned to questions in American newspapers about whether she fled to our small country. It was a story picked up by several New Zealand newspapers. Belle Gunness was born Brynhild Paulsdatter Størseth on November 11, 1859, in Selbu, Norway to Paul and Berit Storset, the youngest of eight children. By 14, she was working on farms to save money to move to New York, arriving in 1881 where she changed her first name to Belle then moved on to Chicago. She had several jobs including at a butcher’s shop cutting up animal carcasses until she married Mads Sorenson. They owned a candy store which burned to the ground. Not long after their home also burned down. They received insurance payouts for both. It would become a familiar theme in Belle’s life. Not long after two babies in their home died from inflammation of the large intestine - something that caused gossip because Belle had not been noticeably pregnant. In 1890, Sorenson took out two life insurance policies, one that would take over when the first expired. There was one day only when both policies were active. Sorenson died of a cerebral haemorrhage on that day. Belle had given him quinine powder for a headache. She collected $5000, moved to La Porte, Indiana and bought a 42-acre pig farm. Belle married again in 1902, to Peter Gunness - who had an infant daughter. A week after the wedding the baby died in Belle’s care. Peter died eight months later due to a skull injury. Belle explained that Peter reached for something on a high shelf and a meat grinder fell on him, smashing his skull. The district coroner convened a coroner's jury, suspecting murder, but nothing came of the case. Belle collected $3000 insurance money for Peter's death. Gunness’ next step was to put marriage ads in newspapers. At least two men, Henry Gurholt and John Moe answered. Both went to her farm and were never seen again. In 1908 it came to an end, when her farmhouse burnt down. The investigation led to the discovery of the body of a woman and three children in the house. The body - which was headless - was believed to be Belle. Then Ashe Helgelien contacted the police about his missing brother Andrew who had been corresponding with Belle. Found on the farm were sacks of body parts. The bodies had been butchered. Five bodies were found on the first day, and an additional six on the second, after that the police stopped counting. Belle’s lover Ray Lamphere was convicted of arson in connection with the fire. He later confessed that she had placed advertisements seeking male companionship, only to murder and rob the men who responded and subsequently visited her on the farm. Lamphere stated that Gunness asked him to burn down the farmhouse with her children inside. Lamphere also asserted that the body thought to be Gunness' was in fact a murder victim, chosen and planted to mislead investigators. Indeed the doctor who performed Belle’s postmortem testified that the headless body was five inches shorter and about fifty pounds lighter. No explanation was provided for what happened to the body's head. All of this led to speculation, including whether she might have fled her. In more modern times there was an attempt to answer the question - with DNA tests run on the exhumed body. They proved inconclusive. Belle was supposed to have been buried in Forest Home Cemetery but was she? And if she escaped and came to New Zealand there was never any sign of her old activities. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed