|

It’s been a year since we launched Genealogy Investigations and then started telling you stories.

The ones here are interesting people and facts we have come across but everyday as part of our business, we hear stories that never make it public. So we thought we would tell you a few - carefully edited to protect the privacy of those involved. Late last year we were able to reconstruct a whole family history - from arrival in New Zealand to nearly modern day for a client whose family had been split up and children adopted into different families. They had lost all the little things we all take for granted. We were delighted to be able to tell them that some of their ancestors were world famous in New Zealand and where they could see the portraits of their family members. We have found the father of an adopted client - who was himself adopted - which meant quite a bit of hard research to put dates, time and places together. We have searched for people up and down the country and overseas, putting families back in touch with each other sometimes. We tracked down a chap in Australia, during a full lockdown, who was unable to work, and were able to put him in touch with the lawyer who was looking for him as a beneficiary of a will to give him the inheritance left to him. We hunted for the beneficiaries of a New Zealand estate in Ireland (with some help from some new Irish friends!). We found the heirs of a long-since deceased land owner from more than 150 years ago for a lawyer to see what they might be entitled to. We managed to find one Smith (turned out to be spelled Smyth) out of millions. And just last week, in the midst of a new Covid panic, we found a homeless guy who had not been in contact with his family for 25 years. And along the way we have uncovered many stories and reunited many people. The year has taken us places we never thought about and we are always learning new things. We love finding people! We would love to hear your own success stories finding your own people.

0 Comments

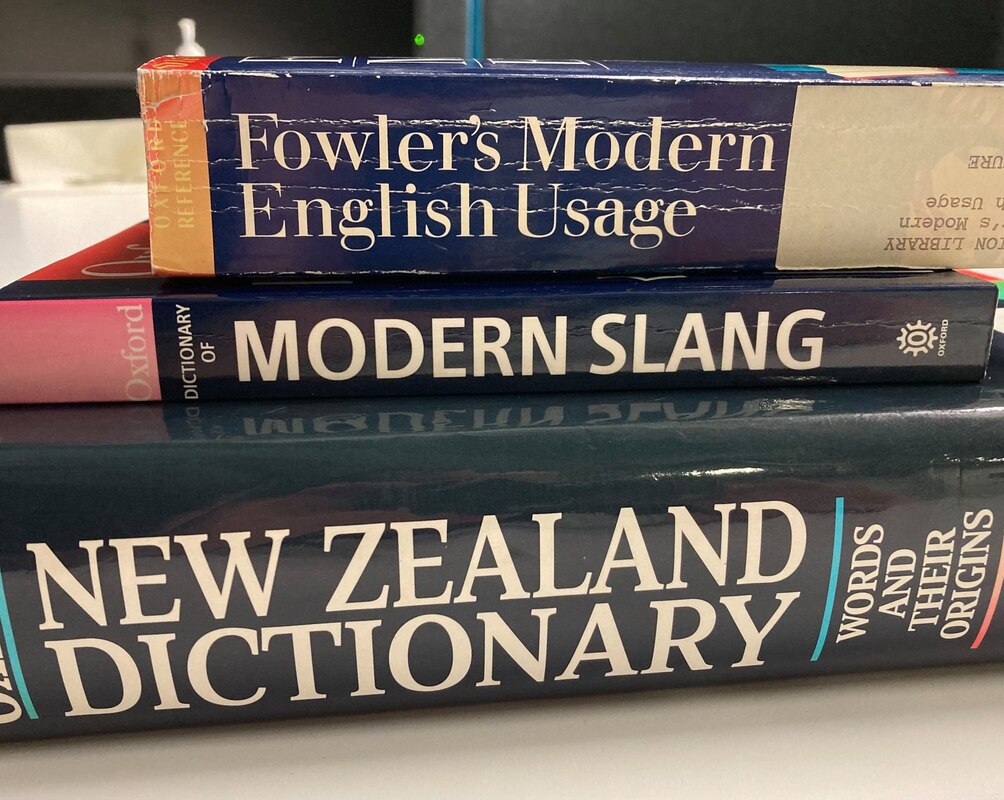

It was a chance argument between his father and a neighbour that made Eric Honeywood Partridge interested in words, becoming New Zealand’s world famous lexicographer.

A large slow bee flew past the pair and one called it a bumblebee and the other a humblebee. Fascinated, young Eric, who only that year had learned to use a dictionary, found both had been in use for hundreds of years. It was the start of a career in words that would define him. Eric was born on February 6, 1894, in the Waimata Valley, north of Gisborne, the oldest son of John Partridge, a glazier, and Ethel Norris. He was the first caucasian born there. His father was better educated than most farmers, he knew Greek, Latin and French and passed his love of learning to his son. The family moved to Queensland, Australia in 1908 when Eric was 14, and for the first time heard a lot of different slang. He got himself a notebook and wrote down all the new words he learned. Eric studied classics before going to the University of Queensland. For a short time he worked as a school teacher but in 1915 he joined the Australian Imperial Forces and served in the infantry during World War One where he was wounded in the Battle of Pozières in France. He was leading a group across No Man’s Land at the time. While there, Eric became interested in how soldiers talked and gathered up all the strange expressions he heard. He returned to the university in 1919 receiving a Bachelor of Arts. After becoming a travelling fellow at Oxford University in English he went on to do a Masters of romantic poetry and comparative literature. Eric taught at a grammar school briefly before taking a lecturing position at the Universities of Manchester and London. From 1923 he occupied a desk in the British Museum Library for 50 years. Eric married Agnes Dora Vye-Parminter and had a daughter. He founded a publishing company and wrote under the pseudonym Corrie Denison. But his biggest work, in part because of the bumblebee incident, was on slang and went on to write the 1230-page Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. He returned to war during the Second World War serving in the RAF’s correspondence department. He wrote over 40 books on English language and tennis, which he loved to play. He never returned to New Zealand but called himself a loyal New Zealander. He died in Moretonhampstead, Devon in 1979 aged 85. Eric once said he was tired of being called the dictionary man or the word man so instead great American literary critic Edmund Wilson dubbed him The Word King. The large memorial at Bastion Point is testament to how loved first Labour Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage was.

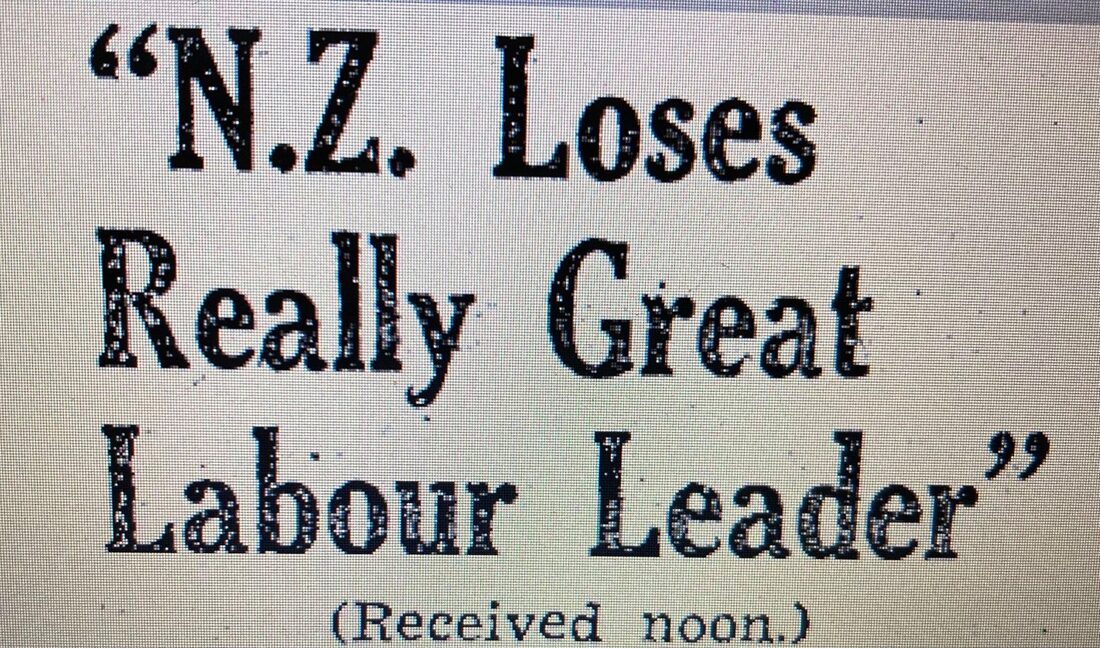

But in 2003 when the memorial tomb was opened 63 years after his death, the coffin was gone. Startled beyond belief, the team of experts who had gone in to determine if there was any damage, had to report he wasn’t there. Savage was born March 23, 1872, in Australia, the youngest of eight children and came to New Zealand in 1907. A trade unionist, he was elected as Auckland Trades and Labour Council president and supported the formation of the Labour Party. He was elected leader unopposed in 1933. He then led the party to its first electoral victory in 1935 and then again in 1938. He won public support for economic and social welfare policies. His government joined Britain in declaring war against Germany in 1939. He was however in declining health, suffering from colon cancer. He died on March 27, 1940. A state funeral was held with a requiem held at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hill St, Wellington before his body was taken to Auckland by train, stopping frequently for people to pay their respects. He was temporarily interred in a harbour gun emplacement then moved to a side chapel at St Patricks Church while a design was created of his tomb at Bastion Point. He was finally laid to rest there. But when archaeologist Doug Sutton and a team went to check 63 years later, they were dumbfounded to find his coffin missing. Savage had originally been there, the coffin visible through barred windows in the doors. But by the time the memorial was opened he was gone. For two years the hunt for his body was on. A radar scan failed to reveal it and there was even a fear that the body had been hidden to prevent it being taken by the Japanese during the war. Then it was thought he might be beneath the floor after a note was found in correspondence between Internal Affairs and the Public Works Department But it wasn’t until a large fissure opened in on the northern side of the memorial that the experts began to wonder. Using geo-technical instruments they began searching and found it in a vertical shaft below the sarcophagus. And there he was 200m down, where it remains to this day. Mystery Creek is best known now as the usual home of Fieldays which has its last day today.

But as it turns out how the area got its name is a mystery in itself. One of the least spooky tales is one of gold robbery in 1867. Waikato War veteran Christian Hansen lived on a farm on the main section of the main route to Hamilton via Ōhaupō to Te Rore. It was remote and at night, very dark. He was used to travellers knocking on his door to ask directions. But when two men entered his home, threatened him and took his savings of 21 gold sovereigns (a huge sum back then!) he reached for his rifle. It all went wrong when one of the robbers grabbed it and instead shot him in the left wrist. They took off and Hansen was left to make his way to Orum’s Hotel where they sent for the doctor. The hand had to be amputated (without anesthesia!). The robbery itself was a mystery, made even more so when a few months later when another settler, looking for a lost cow, found the body of a man that had been strangled. The working theory was one of the thieves killed the other and took off with the money. But it's not the only story. Another was the sudden disappearance of a soldier, seen crossing the gully, only to disappear, never to be seen again. Yet another is about a murder committed nearby and the fugitive hid nearby. When a police constable went to find him, neither one of them was ever seen again. A saddled horse apparently called Mystery found wandering in the gully is another one. No rider was ever found. There is also an intriguing story about the attempted murder of a bank clerk but that was much later and we’ll have more about that in another post. What we can say is that since the records of newspapers began Mystery Creek was already called that. One of the earliest news stories in which the name was used was from 1870. One more little mystery is what happened to Mr Hansen. There are no records of his death or where he is buried. Do you know another story about Mystery Creek? A boring debate in Parliament over the Merchandising Marks Bill on 22 September 1954 took a sudden turn when New Zealand’s first woman cabinet minister Mabel Howard took out two oversized pair of women's knickers and began waving them around.

It’s not likely that women’s bloomers were seen in public all that much, let alone in the seat of power. It must have been a shocking moment for the era, and in fact, the response from the mostly male MPs was to burst out in peels of incredibly immature laughter and giggles. Miss Howard, who wanted to ensure that women's undergarments would be labelled in inches in future, was trying to make a point about the lack of standardised sizing by showing that the bloomers, which were both labelled OS, were actually quite different in size. "I have two articles of underclothing here, both marked OS and both of good quality, and now that I am holding them up, I would remind Members who are laughing that this is not a joke. Let them ask their womenfolk, if they are big women, if they think it is a joke when they go into a shop and buy a garment marked OS and find that it will not fit them. Of course it is not a joke; it is a very serious thing for women." Mabel Howard was no stranger to getting her point across. Born on April 18, 1984, near Bowden, Australia, she moved to New Zealand in 1903 with her father Edwin (Ted) Howard and sisters Adelaide and Elsie after her mother Harriet Garard Goring died of tuberculosis. Her father had originally been a sailor who had deserted his ship to marry Harriet. Howard joined the Christchurch Socialist Party while attending the Christchurch Technical Institute before starting work as the secretary for Canterbury General Labourers’ Union. Howard was a Christchurch City councillor for some years and when her father, Ted - himself a Member of Parliament - died in 1939, she hoped to take his place. That didn’t happen, the Labour Party chose another candidate. Howard was elected to Parliament in the Christchurch East electorate in a by-election in February 1943. In 1946 she won the then new electorate seat of Sydenham with over 75 percent of the vote. Even when Labour was in opposition in 1963 and 1966, Howard was re-elected with large majorities. She held the seat until she stood down in 1969 after a mandatory retirement age was introduced. In 1947 she was appointed the Minister of Health and Minister in charge of child welfare and in 1957 became Minister for Social Security, Child Welfare and Women and Children. A staunch trade unionist, she often spoke on topics like social welfare, the rehabilitation of service men and women and the needs of women generally. Howard went on to introduce important legislation which led to better treatment of tuberculosis, the regulation of physiotherapists and occupational therapists, the teaching of obstetrics and gynaecology and improving facilities for the mentally ill. A topic she was passionate about was consumer protection, which led to her infamous stunt with the knickers. It also led to her throwing a stone on the House floor warning that people buying coal might end up with more stones than coal. With her four-foot 11-inch (1.5m) height and penchant for speaking her mind, she was a great character, a proponent of equal pay, an animal lover who adored her cats and was President of the Christchurch SPCA for many years. She was such an animal lover that when she found two mice in her office and decided to keep them as pets, naming them Sid and Keith after former National Prime Ministers Sid Holland and Keith Holyoake. In 1961 she pulled another stunt, saying she would be seeking re-election in slippers, since it was impossible for women to buy shoes other than those with stiletto heels and pointed toes. By 1969, her health was in decline and she was in the early stages of dementia. Sadly, a court order saw her committed to Sunnyside Hospital, Christchurch, where she died in June 1972. She never married (although she said she had plenty of offers) and had no children. She is buried at Bromley Cemetery in Christchurch. Rice Owen Clark got off New Zealand’s first charge of bigamy in 1849 because there was no proof that his first wife was still alive, where she was or even if she was a woman. Even though she was sitting in the back of the courtroom.

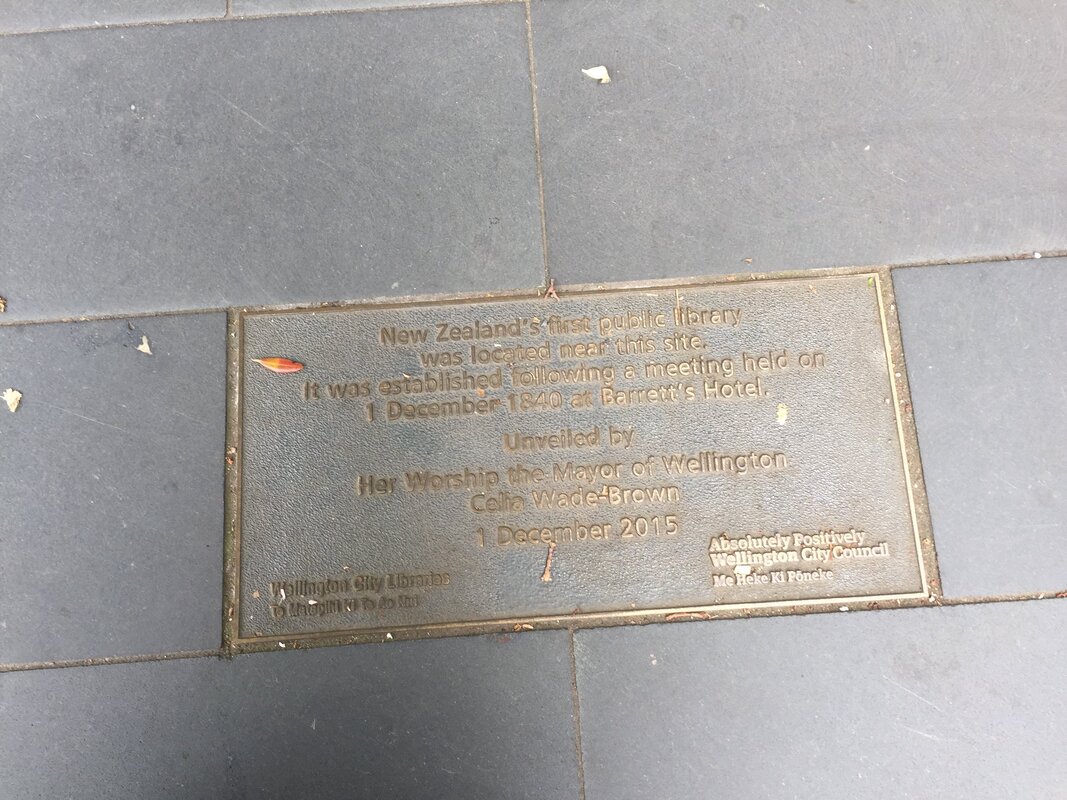

Bigamy used to be a bit more common back then than now, usually because it was difficult to verify whether new immigrants coming to New Zealand were not already married when their new marriages were registered here. Clark (sometimes seen as Clarke) however got the ignominy of a Supreme Court trial. Clark was born August 19, 1816, in Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire in England to Josiah Clark and Ann Rose. He had a good career as an underwriter with Lloyds before he immigrated to New Zealand in 1841 on the Gertrude. At the Supreme Court in Wellington, the jury was told there was a marriage to Ann Insgoldby (records show the name was more likely to be Ann Inglesby) in England. Indeed, records now show a marriage recorded at Christ Church, Spitalfields, London England for December 14, 1835. On the ship to New Zealand, Clark was assigned a berth as a single man but rumours began that he and Ann, who was travelling on the same ship, were married. But on arriving in Port Nicholson they went their separate ways and Clark later met and married Louisa Felgate. Prior to this marriage, he had inquired with Methodist minister James Watkin if he was able to marry Louisa. Watkin performed the marriage ceremony. The Clarks lived a settled life until suddenly Rice was brought before the Supreme Court, on September 1, 1849, on the charge of bigamy. It was the first case of bigamy to be heard in that court in New Zealand. Initially Ann was said to have returned to England, but she turned up at the police station in Wellington alleging her husband's misdeed. The trial was not only odd, but clearly deficient, much to the fury of Justice Henry Chapman. The Crown brought no witnesses to either identify her or to claim she was alive. Even though she sat through the whole trial. There were no records before the jury and, as his supposed wife, Ann could not be called to give evidence against him. Clark himself said whoever the person called Ann Ingoldsby was, he had not consummated any marriage - of any sort - with her. The implication was that Ann was not actually a woman, although there was no proof of this. In the end, the jury found him not guilty. Clark and Louisa moved to Auckland in 1854 with their first child, initially living in Devonport. After selling that property they moved to Hobsonville where he was the first European settler. Despite his ‘nefarious’ background, Clark is best known for founding the pottery and pipemaking family firm that produced the Crown Lynn range of ceramics which later became Ceramco in 1974. Clark died on June 16, 1896 and he and Louisa are buried at Hobsonville Cemetery, near the church he helped build. It is not known what happened to the mysterious Ann. A small plaque underfoot by Wellington’s cenotaph is what remains of New Zealand’s first public library.

Unless you look down and take a second to read it, you won’t even know it’s there. But in 1841, the Port Nicholson Exchange and Reading room took up residence in what was formerly Richard Barrett’s house on Charlotte St - now the corner of Molesworth St and Lambton Quay. It was hardly a resounding success. It was badly located (most people lived closer to Te Aro) and its fee, £5 to join with an annual subscription of £2 - some $700 in today's money to join and $200 to subscribe - put it way out of the reach of most people. Still it was a valiant effort - it’s initial offerings were mostly donations of books often from the very first settlers to Wellington. When there were protests that the ‘working’ man could not afford it a competing exchange was set up in Te Aro. The new Wellington Exchange did well but the Port Nicholson one failed to get its own members to pay up, let alone attract new interest and by 1842 it was closed. New Zealand’s first public librarian was Dr Frederick Knox. Knox was born on April 3, 1794 (or 1791) in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was the ninth child of Robert Knox and Mary Knox (nee Scherer). He was employed by his anatomist brother Robert (later discredited in a body-snatching scandal) as an assistant. He was licensed by the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1831 and had a small practice. Dr Frederick Knox emigrated to Wellington, as the ship's surgeon on the New Zealand Company vessel Martha Ridgway arriving in Mar 1840, with his wife Margaret (nee Russell) and their then four children. He had purchased a land entitlement (number 76), a section in Willis St but lived in Johnsonville initially and later in the Hutt. He was appointed the librarian in 1841 with a princely salary of £75. His main interest was natural science and he was a member of the New Zealand Institute from 1867. Between 1855-57 he served as a resident medical officer to the Karori Asylum. He also served as coroner in the Wellington district in Porirua from 1861. He and Margaret had six children, one son and five daughters. He died on August 5, 1873 aged 79 (or 83) and is buried in Bolton Street Cemetery in a public plot - although its location is unknown. Ernest Robert Godward is a name you probably don’t know, but this astonishing man is the mind behind one of New Zealand’s most iconic inventions.

We’ve all seen one. It was the egg beater in your grandmother’s kitchen. A handle at the top and a handle to turn the blades. Designed as a non-slip egg beater, it was so common, I bet you can picture it. You may even still have one. Well, that was Ernest Godward. He was born in London, England, on April 7, 1869 to fireman Henry Robert Godward and Sarah Ann Pattison. His parents sent him to a prep school at age 12, but Ernest ran away to sea reaching Japan where he was working on a cabling project before he was returned by the British Consul. He ended up apprenticed to engineers although he went back to sea in 1884. In 1886 he came to New Zealand arriving in Port Chalmers aboard the Nelson, where he jumped ship. He was a man of many many talents. He played a number of instruments, including the banjo, was athletic, cycling for the Invercargill Cycling Club and was one of the founders of the Invercargill Amateur Swimming Club along with rowing and boxing. On 28 January, 1896 he married Marguerita Florence Celena Treweek and the couple had 10 children. Nine of their own plus a niece of Marguerita's But it was the numerous inventions he was most noted for, with more than 30 patents applied for. In 1907 he designed and patented that iconic egg beater. Among his other inventions there was a new post-hole borer, a new hair curler, a burglar proof window and a hedge trimmer made from bicycle parts. He also founded the Godward Spiral Pin and New Inventions Co Ltd - which was listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange. He sold the American rights to his spiral hairpin and was said to have made his first million dollars that way. His most famous invention, in 1926, was an economizer for a fuel engine which was used by public transport systems in America, allowing them to use fuel oil instead of petrol. In all, Goddard created 72 different carburettors Even that was not his only claim to fame - he was involved in Southland’s first hot air ballooning and built Rockhaven, his private residence in Invercargill, which is still standing and considered an historic building. The garage where he did a lot of inventing is still on the property. He spent the last 20 years of his life in America, visiting New Zealand and his wife from time to time. However, during the stock market crash of 1929 he lost heavily, making only a partial recovery. He died of a heart attack on December 2, 1936 on board the SS Mongolia out of Gibraltar while returning home to Invercargill. True to form, he had won a skipping contest on board the day before. He was buried at sea. Ever since we brought you the story of Carl Weber - whose name was given to a little Southern Hawke’s Bay township, we have come across others whose names are familiar to us, even if their stories aren’t. So we thought we would tell you a few. Here's one.

James Heberley was a whaler, boat pilot, settler, mountain climber and liked to forecast the weather. But it was how he did it that captured attention. Every time he was asked about the weather he said it would get worse. Eventually he was nicknamed Worse Heberley - then Worser. Which led to that name being given to Worser Bay in Wellington, where he had lived in the pilot’s house which still stands today. Heberley was born in Wyke Regis, a coastal town in Weymouth, England on November 22, 1809 to Johann and Elizabeth Hebley. The spelling was later changed. Johann himself was a master mariner and it did not take long for James to set out to sea, running away at the age of 11. He started sea life as a captain’s apprentice and cabin boy, sailing out of London. He kept a diary (now at the National Library) of a great deal of his life. The early section of the diary recounts Heberley's experiences as a captain's apprentice and cabin boy on vessels sailing out of London to many destinations including Hamburg, Sydney and the West Indies. Much of the later narrative describes whaling and the life of a whaler in Cook Strait and the Marlborough Sounds. Accounts differ of when he arrived in New Zealand, either 1825, 1827 or 1830. But by 1830 he was living in Queen Charlotte Sound where he knew Māori chief and war leader Te Rauparaha and witnessed many fights. He was a whaler at Te Awaiti and Port Underwood and later became a ship’s pilot for the New Zealand company, piloting the Tory into Wellington in 1839. In 1842 he married Maata Te Naihi Te Owai at Cloudy Bay. She was also known as Te Naihi Te Owai, Mata Te Naehe or Te Wai Nahi. She was the daughter of Aperhama Manukonga and granddaughter of Te Irihau. Heberley spoke Māori well and was often included in negotiations over land. After Maata's death in 1877, he went on to marry Charlotte Emily Nash. Heberley, along with Johann Karl Ernst Dieffenbach became the first European men to climb Mount Taranaki (Mount Egmont), standing on the summit on Christmas Day, 1839. His account of this climb is in the National Library. Local Māori thought they were nuts to do it. In June 1843 Herbely gave up his role as a pilot operating in Worser Bay and began fishing and returned to whaling. His death at the age of 91 in 1899 was just as dramatic as the rest of his life. He went missing from his Picton home and was ultimately found in Picton Harbour - according to one account “standing upright in the water, his feet just touching the bottom, his eyes open and his walking stick in his hand, the water just covering his head. The only thing giving a clue as to his whereabouts being his hat, which was floating on the water nearby.” He is buried in Picton Cemetery. His descendants have been celebrated Māori carvers and many have retained their connection to the sea. Have you ever wondered how somewhere got its name. Tell us and let's see what we can find. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed