|

A lot of Hawke’s Bay looks the way it does because of one man.

Streets, the waterfront, railway lines and drainage were all under the overview of Charles (or Carl) Hermann Weber, a noted surveyor who mysteriously died doing his job. The tiny Central Hawke’s Bay town of Weber was named after him along with a street in Woodville. Weber, some 28 kilometres south-east of Dannevirke, was founded as an overnight stop for coach teams heading for the coast. It was a thriving town at the turn of last century. Weber also had a little cemetery - now just a memorial. Charles Weber is, however, not buried in his namesake town. Weber was born in the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Kassel in Germany or what was called Bavaria in 1823. He served in the Army and attained the rank of Captain of Engineers. But in 1848, after he refused to fire on people during a revolution, he was cashiered. He fled to the United States of America and there he was one of a party, under the leadership of General Fremont, which helped lay the transcontinental railway from New York between 1846 and 1853. Weber moved on to the romantic-sounding South Seas Islands, which we now call the Pacific Islands, as part of the sandalwood and beche-de-mer (sea cucumber) trade. Next he spent time in South America before moving on to Australia where he bought a large cattle run but he was forced to give it up when gold fever struck and he was unable to keep farm hands. It was in Sydney that he took tests to become a surveyor and was lured to New Zealand in 1860 by the founding of a new province - Hawke’s Bay - to be the chief surveyor. In 1866 he became the Provincial Engineer of Hawke’s Bay, a position he held for five years before joining the Public Works department employed in the preliminary survey of the Manawatu railway line. It was Weber who supervised the construction of the Napier breakwater, advised on massive drainage projects and on the development of Napier Harbour. He was also involved in the planning of the train and road through the Manawatū Gorge. After a time in private practice he retired, but continued to take an interest in the nearby town of Woodville. In 1886 Weber headed out to look at some land near Mangatainoka. He was last seen on the coach near Pahiatua. He went into the bush and disappeared. Searches were mounted and rewards offered but it would be three years before his body was found by bush fellers near Makakahi. An inquest returned the finding that he became lost and died of exposure. Weber is buried at the Old Napier Cemetery with other members of his family. He was survived by his wife Ellen and three sons and two daughters.

1 Comment

We’re going to keep looking for James Collins.

You hear so many terrible things about Facebook; interference in politics, privacy breaches and bullying, it’s easy to be cynical. When we decided to start Genealogy Investigations, we looked at how we would use Facebook to reach people. Yes, we are a business, but we also wanted to tell stories and reach out. And it has exceeded our expectations. Not only are we able to share tales that might be forgotten and to honour people, but it just shows Facebook can be a force for good. So many of you were interested in the story of James Collins, who was buried for three days beneath the rubble of the Park Island Old Men’s Home in Napier after the 1931 earthquake before being rescued, especially that the poor chap was buried without a headstone in Dannevirke, that we have decided we are going to investigate further. It constantly surprises us how willing people are to help find a family member no one has spoken to for a while, find a person who has moved overseas and help find records on the ground in another country. There is a vast amount of information on the Internet, but it is not always a substitute for searching through hard copy records. We have found people willing to go to local offices to check things, to cemeteries in far flung countries to take pictures, to reach out to others and help us - in some cases - to reunite families. And in today’s world a bit of kindness is badly needed. Some of you have reached out to help with ideas about James Collins - thank you all. We will let you know how it goes. This is what Facebook should be for. On February 8, 1939, death came for 54-year-old Patrick Henry Shine, an Auckland storekeeper and former soldier.

But it was only the start of his adventures. He was buried the next day by his grieving family in the Waikumete Soldiers' Cemetery, Auckland. He was survived by his first wife, Georgina and son Frederick and his second wife, Madge. Shortly after however, in a truly extraordinary legal case, his body was dug up by two body snatchers who used him in an attempt to fake one of their death’s for insurance purposes. Gordon Thomas McKay (alias Tom Bowlands) and labourer James Arthur Talbot had arrived in Auckland from Australia aboard the Mariposa two days before Patrick died. They rented out a garage and the day after Patrick was buried they dug him up and removed his body to a garage they were renting in Avondale. McKay and Talbot then rented a bach at Piha which they promptly burned down - with a body inside. It was intended that people would believe McKay, whose life was insured for £50,000, had burnt to death while Talbot survived. The charred remains were buried, again in Waikumete - this time under the name McKay. Suspicions soon arose, however, and the Australian insurance companies, holding the policies on McKay's life, wanted the death investigated. Patrick’s original grave was opened, and it was of course empty. Talbot was arrested and a search made for McKay who was found 12 days later at a boarding house in Parnell registered under a fake name. They were found guilty of arson and the very rarely used charge of improperly interfering with a dead body, both receiving jail terms. And Patrick Shine was buried again - this time to rest in peace in the same coffin and grave he started in. New Zealand has many lost or hidden cemeteries. We’re going to see which ones we can find. Bridge St Cemetery, Lower Hutt. It’s a tiny peaceful little spot. On the corner of Lower Hutt’s Bridge St and Marsden Street is the remains of a cemetery. Through a little gate into a tree-covered yard with pretty flowers and a few notable memorials, the Wesleyan (or Methodist) Cemetery seems like you are stepping out of a city into a place out of time. While it is still maintained, some graves have been lost to road widening - with a memorial stone now naming those whose final resting place has been disturbed. There are 51 graves recorded there but it is likely there are more than 100. Of the few headstones that remain there are the names of families that were instrumental in the founding and development of Lower Hutt, the Sanson family, Frethey family, the Knights and William Bassett, shoemarker of Petone and his wife Mary, along with a poignant memorial to Thomas “William” Webb, a private with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force army who died at sea on board the troopship Mokoia on December 21, 1917 at the age of 27 headed for Europe, however he never saw battle. He died of illness aboard ship.

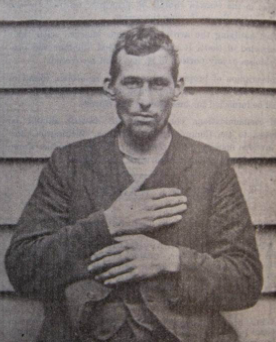

He is also on the memorial at Karori Cemetery. The Knights, William and Mary Ann and their five oldest children were some of the first settlers in Petone arriving on the Duke of Roxburgh in 1840 from Cornwall. Son James Penrose Knight was a borough councillor and his son Willoughby was deputy mayor. If the names are familiar to those from Lower Hutt its because there are a number of street named for them, Penrose St, Knights Road, Willougby St and Frethey Grove. The little cemetery, still cared for by Hutt City Council, is all that remains of the original Wesleyan church on the banks of the Hutt River established in 1845 and stood nearby for only a few years before moving to Laings Road. There are drawings of the original church in the Alexander Turnbull Library done by Marion Swainson. Do you know of one of these ‘hidden’ cemeteries? Joseph Pawelka, NZ Police Gazette Notorious Manawatu criminal Joseph John Thomas Pawelka had a pretty short and unremarkable list of convictions, but his actions led to two men being shot dead and panic in the communities of the Manawatu, Rangitikei and Tararua regions.

Pawelka was born in 1887 in Oxford, Canterbury to Moravian immigrants and brought up in Kimbolton in the Rangitikei. At 13 he left school and apprenticed to his uncle at a Palmerston North butchery. In 1909 things started going downhill for Pawelka when a bout of typhoid fever put him in hospital for five months and saw him have part of a lung removed. The next year he married local girl Hannah “Lizzie” Wilson, but the relationship did not go well despite the impending birth of their child. At the end of that year Pawelka first came to police attention after he attempted suicide, a criminal offence at that time. Lizzie was granted a separation. A few months later, the Pawelkas turn up at Palmerston North police station after a dispute. Lizzie told them Pawelka had a gun, which he did, and it duly handed over. Police then searched his house for ammunition, unexpectedly finding a large amount of property recently stolen in burglaries. It was unclear whether Pawelka had committed these crimes, or had merely bought the furniture and other items from someone else. Nevertheless, he was charged with theft and taken into custody. This is where things began to get even worse. Five days later, Pawelka used two upturned buckets to help him climb the wall of the Palmerston North Gaol, steal a bicycle and make an escape. He was recaptured after two days and this time taken to the more secure Terrace Gaol in Wellington. On March 23, 1910 Pawelka was taken to the police cells in Lambton Quay as he was due to appear in court. When the gaoler forgot to lock the cell door, Pawelka took the opportunity to escape again. He headed north and a trail of burglaries, an armed robbery, three arsons and a shoot-out with police in Pahiatua were attributed to him. Fearing Pawelka would target their homes, hysteria began to overtake the region’s residents. Extra police were called in and residents volunteered to help hunt for the wanted man. The crimes continued and on the night of April 9 a former employer of Pawelka’s called police claiming he was trying to break into his house. Officers rushed to the house and in the darkness a struggle ensued between the apparent burglar and Sergeant John McGuire. Several shots were fired by police and the burglar, one of which hit McQuire in the stomach. He died four days later. Two days after McQuire’s shooting, a volunteer searcher from Pahiatua, hairdresser Michael Quirke, was shot in the head by another searcher in Palmerston North after he did not respond to calls to identify himself. On April 17, Pawelka was finally captured by police in Ashhurst, ironically one of his captors being the officer who had left the cell door unlocked. Pawelka was charged with the murder of Sergeant McGuire, robbery, theft, arson and escaping, but was eventually convicted of only the last three. The judge sentenced him to a total of 21 years in prison. Despite the community’s earlier fears of Pawelka, his lengthy sentence provoked protests, a deputation to parliament and a 15,000-signature petition seeking a reduction. Pawelka made further attempts to escape from prison and finally, on April 27, 1911, succeeded. At the time Pawelka seemed to disappear into the ether, but many years later it was revealed that he had made it back to Kimbolton and, with help from those who knew him, eventually to Auckland. From there he either sailed to Vancouver, Canada on the Makura, 119 years ago next week, on February 16, 1912 or to Sydney on another ship. His last resting place remains a mystery, but those of the two men killed during the manhunt are not. Sergeant John Patrick Hackett McGuire is buried in Karori Cemetery in Wellington. He was 41. Michael Patrick Quirke is buried in Pahiatua/Mangatainoka Cemetery. He was 36. Across from the Hawke's Bay Earthquake Memorial at Park Island Cemetery is another less well known one - dedicated to the 10 men who died when the launch Doris collided with the ship Tu Atu in Napier harbour.

Erected by the NZ Waterside Workers Federation, it reads, “No pains, no griefs, no anxious fear can reach our loved ones, sleeping here.” The accident left 26 children fatherless. It was a calm mildly rainy night on December 28, 1932 as the Doris, with 31 watersiders aboard, headed for her moorings at the inner harbour. They had been working in the freezing chambers aboard a ship and were heavily dressed against the cold. At the same time, the Tu Atu left her berth at Ahuriri and headed out. She tried to stay in deeper water on the outward channel. The Doris, a bright white oncoming light to the men aboard the Tu Atu, looked initially to be on the other side of the channel. But at about 150 yards away both lights of the Doris could be seen, which meant it was on a collision course. The Tu Atu was in a narrow deep water channel with rocks on either side, unable to turn away and the crew watched in horror as the Doris disappeared under the bows of the Tu Atu. Boats, trawlers and tugs hurried to the area to help pull survivors from the water. Then the search began for the bodies. Walter Andrews, Robert Aplin, Alexander Boyd, Eddie Cooper, Harold Johnson, Thomas Kitt, Norman Low, Jethro Metcalf, John Wilson and James Woods lost their lives. A Marine enquiry into the disaster found that the helmsman of the Doris, Erik Mentzer, was directly responsible for attempting to cross the Tu Atu’s bow. Witnesses said the Doris appeared to try and change its course just before the collision. Erik Gunnar Mentzer was buried in the Hastings cemetery in 1969. Today the memorial lies in the shadow of the earthquake one, smaller but no less tragic. James Collins lived almost unnoticed for most of his life before suddenly becoming famous at the age of 91.

Three days after the Hawke’s Bay earthquake in 1931, when hope was fading of find anyone alive, the nonagenarian was pulled alive from the rubble of the Park Island Old Men’s Home in Taradale. The home was one of 15 buildings in Hawke’s Bay whose collapse led to the largest number of fatalities. Obviously a sturdy chap, even at that age, Collins tried to run when the earthquake hit, but was knocked face down on to a mattress as the building collapsed around him. It saved his life. Three days after the quake, a police officer heard someone calling out and a rescue team uncovered Collins, who while injured, was in remarkably good condition. Born in Tipperary, County Cork, he traveled as a military man in India. He had been in what was then known as Zululand and in Capetown. Something of an athlete in his young days, he won prizes for high jump, long jump and running. While he was recovering in hospital he recounted his time buried and waiting to be rescued being terribly thirsty and wishing for a gallon of beer. Sadly, shortly after his rescue he was admitted to Dannevirke Hospital and died in November 1931. Even sadder, his grave, one of the earliest ones in Dannevirke’s Mangatera cemetery, has no headstone. He was believed to have no family. Of the eighty people at the Home, 80 survived and 14 died in the earthquake, although a few died later. Everyone knows the basic story of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake. It hit at 10.47am on Feb 3, 1931 and was listed at 7.8 on the richter scale.

The official death toll is listed as 256. It’s unclear, however, if that should be the final number. Some victims were never found and some of those who died from their injuries may not have been counted among the final dead. But alongside the well-known facts are snippets of information that have been forgotten over time. Here are a few. In just two-and-a-half minutes the earthquake moved sharply up and then just as sharply down. Much of Ahuriri lagoon was uplifted during the earthquake, exposing about 3000 hectares of seabed forming a land bridge between Napier and Taradale. The Hawke’s Bay airport is today on this land. Many of those who died were not killed during the earthquake itself. Instead, fire swept through the damaged stores and buildings killing many trapped people before help could get to them. HMS Veronica was in the harbour and during the earthquake was left nearly high and dry as the sea receded. But the sea swept back and the sailors scrambled ashore to help. She was able to contact two others, the Diomede and the Dunedin who rushed to Napier with food, medicine, tents, blankets and a team of doctors and nurses. Prisoners from the Napier jail were working on Bluff Hill. Four of their number were buried in a landslide. They were able to dig two out. None of the prisoners took advantage of the situation and were locked up in the jail again. More than 900 aftershocks were recorded and lasted until December that year. Explosives were used to create a hole big enough for the first 54 burials. While the official death toll is 256, there are actually 258 names on the memorial. Some of the stories of individual deaths became known. Gwen Butler, aged 21, was working at the Griffiths shoe store in Hastings. She survived the original quake. Gwen and the other staff helped evacuate the store but when someone mentioned to her that the money was still in the till she went back inside. A large aftershock hit, collapsing the brick wall of the bank next door, which fell into the store killing Gwen. She is buried in the Havelock North cemetery. Alfred Evers-Swindell’s name is on the list of the dead. If his name is familiar it's because he was the brother of Garry Owen Evers-Swindell - grandfather of the Olympic gold-medal-winning Ever-Swindell twins. One boy, originally counted among the dead, was later taken off the list when it was discovered his body had already been in the morgue, which had collapsed during the quake. More than half of the fatalities came from the collapse of just 15 buildings, like the Nurses Home on the hill, the Roaches store in Hastings and the Park Island Old men’s home. Napier used to have trams. But after the quake the tracks were left twisted beyond recognition and were never restored. And Napier’s now iconic Art Deco-look is a direct result of the rebuilding done after the earthquake. We have one more tale to tell from the earthquake. An amazing story of survival which will be published this coming Saturday. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed