|

Nearly everyone will have used a Hansells product. Remember Jungle Juice?

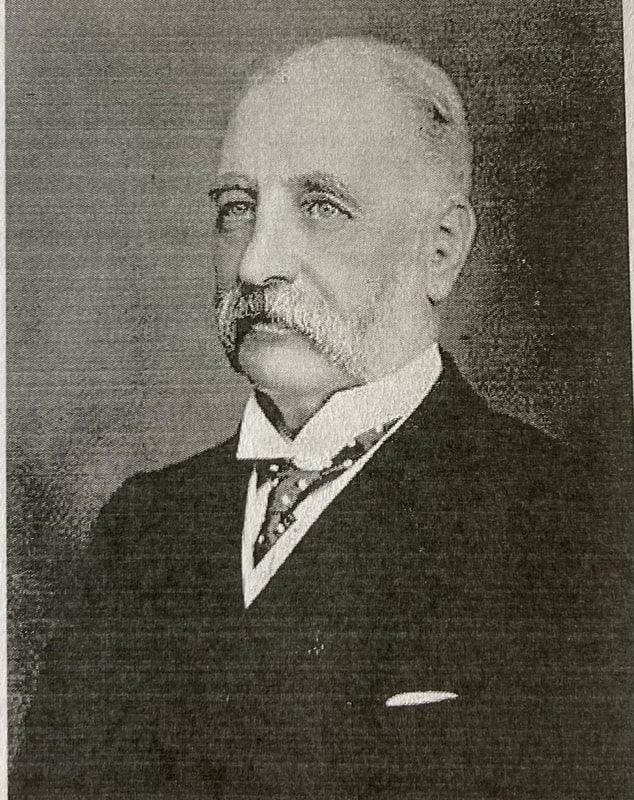

You probably have one in your kitchen right now. Check the baking soda, or food flavourings. It is still operating after 88 years - at the same Masterton premises where it was opened in 1934. The man behind it was Leslie Beauchamp Maunsell, son of John Frederick Maunsell (whose father Robert came from Ireland with his wife Susan in 1835) and Emma. Maunsell was born August 18, 1835, in Tinui, Wairarapa and enlisted when World War One broke out. In 1916 he was reported as having been gassed and taken to an Italian hospital where he recovered. Later that same year he was shot in the chest while in action in France. He received the Military cross for bravery. He met and married Catherine Jane Martyn-Johns in Sussex in 1917. He recovered enough from his wounds to return to light military duty. Back in Masterton he co-founded a company with a chemist only known by the name Hansen. They combined their names to make Hansells. Initially they were making experimental products in a chicken shed on the property with the first products being culinary essences. Many of the brands were household names: Vitafresh, Thriftee, King Traditional Soup, Sugromax, Sucaryl, Hansells and Kings. It was best known for flavour essences, but other products include food colouring, gravy browning, drinking chocolate, drink powders, pancake mixes, baking goods and mousse. The factory was also the family property and staff - who bottled and packaged many of the well known products - were also considered family. Sports were often played on the ground and weddings of staff were held there. Hansells and its various brands were acquired by Old Fashioned Foods Group in 2006. Maunsell died August 18, 1953 and is buried in the Masterton Archer St cemetery. And what about the chemist Hansen? Well, the rumour was that he was wanted in Australia for bigamy so left the company in the early days. Without a first name it's hard to track him but a newspaper article in The Brisbane Telegraph from 1937 lists a Joseph Nichol Peter Hansen, 42 as having appeared in court charged with being married to two women at once. He appears to vanish from sight after that.

0 Comments

In 1874, the remains of huge vertebrae were found at Mount Potts in Canterbury. They were so big, that if they belonged to a creature it would be the biggest to be ever found on earth.

The beast would be over 200 tonnes if the size of the vertebrae were used as a measure. It was named Hector’s ichthyosaur - a massive marine creature - a fish lizard - a reptile that had been on land then returned to the sea. That would make it bigger than a blue whale. But the remains have now vanished, with the rumour being they were on a ship going to London that was lost at sea. The creature was named after James Hector - the father of Te Papa. Another marine creature is better known for being named after him, Hector’s dolphin - one of the rarest and most endangered in the world. Hector was born on March 16, 1838 to Alexander and Margaret in Stockbridge, Edinburgh. He received a medical degree aged 22, but had a passion for geology, which he also studied. He was appointed geologist to an expedition in America to explore new railway routes. An accident nearly killed him. His horse kicked him in the chest. Thinking he was dead, the others dug his grave. Fortunately he regained consciousness before he was buried. In 1862, Hector came to New Zealand to do a geological survey, travelling around the South Island to determine good places to settle. He hired staff to bring him fossils and specimens to categorize. He created a geological map of Otago known as Hector’s map. Hector went on to found the Geological Survey of New Zealand before moving to Wellington to supervise the construction of the Colonial Museum and was the first manager of the Wellington Botanic Gardens. In 1868 he married Maria Georgiana Monro and they went on to have nine children. By 1903 he was unwell and retired - remaining as president of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Hector died in Lower Hutt in 1907 and is buried at Taita Cemetery. In the late 1920’s a mini crime wave was being reported in all the New Zealand papers. They were called the safe blowers.

In November 1929 they blew the strong room door off at the Kiwi Diary company in Christchurch - getting away with £30. They were believed to have got in about midnight - possibly with a skeleton key. It was the sixth similar crime in two weeks. Also hit were the White Star brewery, where a heavy explosive charge was put in the keyhole and blown, the key lock was blown clear off the door and embedded itself in an opposite wall. The Jarrah timber company, and a coal merchant were also targets. But it seemed this particular type of crime was happening all over the country. Earlier in 1929 - in Dunedin safe-blowers got into a post office. Then they hit a cabinet minister's local office. In Auckland, several butcher’s shops and a bottle merchant had doors blown while in August of 1929 £60 was taken from State Coal Depot. In 1930 in New Plymouth at least two including a furniture shop where they got £840. So was a gang of ruthless safe-blowers operating up and down the country? Well, no not really. It was several pairs all using the same methods. The first pair was caught in Auckland in February 1930. William James Leslie and Jack Edward Peters were sentenced in the Auckland Supreme Court to three (Leslie) and two (Peters) years jail. They had been spotted out on the street at night and pounced on by police who found them in possession of gelignite fuses and other instruments. While in Napier, Joseph Coyle and Edward George Stanley Elliott had tried to get into the Napier Railway Station office. They were caught virtually on the scene and later explosives were found in one of their homes. Then in June 1935 safe-blowers hit Hays Ltd, a draper in Christchurch and got £400 in Christchurch. It would be the crime that finished the rush of safe-blowers. Albert William Gauntlett was born in India to father Albert and mother Margaret on June 9, 1908. At some point the family came to New Zealand. Along with Ralph Crosy - also known as Trevor Foote (from Australia) - they led police a merry chase - after they broke into Hays - police became interested in the journey of a Christchurch taxi which headed north. Phones in police stations rang up the South Island as police followed its progress all the way to Picton. There the police waited, thinking the pair were headed for the ferry to Wellington. When they missed the sailing they booked into the Oxley’s Hotel where they were kept under surveillance. Police caught the pair of them asleep in their beds. Most of the money was recovered and the two men were given a police escort back to Christchurch. A jury found them guilty. Both got two years. Justice Northcroft said they appeared to have embarked on a life of crime. Albert married Patricia in 1958 and died the following year in November 1959, he is buried in Mangere Lawn Cemetery. After a criminal life he had apparently settled down. Picture by Jason Dent. In war you have your gear and your buddies. Out in the trenches and under fire, your buddies might be the more important thing in your life.

For Wilfred Lancelot McMurray, he was the one buddy everyone should have. Will, as he was usually called, was born in Auckland in 1895 to Henry and Matilda. He was working as a dentist when war broke out in August 1914. Within a week he had enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Like a great many others, he was, at 19, actually too young. But he altered his birth date by a year. At almost six foot tall, dark-haired and dark-eyed, it would not have seemed out of place. He left and ended up in Egypt arriving in December where they remained until the preparations for the Gallipoli assault. Like a lot of New Zealanders, he landed at Anzac Cove. It’s from a letter home by Private Frank Shirley that McMurray’s heroism is known. It was late April, 1915, when Shirley was wounded after being shot by a sniper and pinned down in an abandoned dugout. He was unable to move due to bullets flying and it was McMurray who stayed with him, talking to him and giving him water. As darkness fell McMurray crawled into the dugout and managed to get Shirley to safety. Only then did it become known McMurray had already saved the life of another man, earlier in and returned to the front line, where he found Shirley, who was his tent mate. Shirley recovered and was lucky not to lose his arm or later his life from infection. In May McMurray was sent with the rest of his brigade to Cape Helles at the southern point of the Gallipoli Peninsula. On the 8th the New Zealanders fought the Second Battle of Krithia and at the end of the day McMurray was reported missing. His body has never been found. He was only 20. McMurray was declared ‘believed to be dead’ by a board of enquiry in 1916 and is commemorated on the Twelve Trees Copse in Helles, Turkey and at the Auckland Grammar School memorial. He was one of 18,058 New Zealanders who died as a result of First World War service and are listed on the Roll of Honour. Frank Shirley went on to live a long life, marrying, having three children and dying aged 82 on January 3, 1975. He is buried in Te Henui Cemetery in New Plymouth. Photo by Stijn Swinnen. Joan Rose Rattray was expected home from school in Hastings, just like she was every day.

But when her two brothers turned up and she didn’t, her mother Hazel Catherine Rattray knew something was wrong. Because it was 1935 and no one’s first thought back then was sinister foul play, she went looking for her six-year-old daughter. But on not finding her she went to the police. A search was started but it was the next day, July 3, 1935, that the little body of Joan was found lying face down at the edge of the old Ngaruroro river. A boy who had joined the search, Frank Shine, found her about 3pm. She had a gash on her forehead and appeared to have had her face deliberately pushed into the muddy bank. The mud held other things - including the impression of a man’s size nine boot. An undergarment of hers was found in the grass along with her hat although police did not think she had been interfered with. She was otherwise fully dressed. The search then began for her killer. One theory was that she had been knocked over by a motorist who panicked and then moved the body but that was discounted. A post mortem showed she died of asphyxiation. Despite police hunting around the country for anyone who might have been involved, no one was ever arrested. A £200 reward was offered (huge money in those days) but brought nothing. But 31 years later someone did come forward. By leaving a suicide note. Arthur Henderson Smith was a former soldier and railway worker and labourer who hanged himself aged 62. A suicide note read he felt he had gone insane with his wicked ways. He thought he had committed the murder at the Karamu Creek years ago but could not remember taking the child off the road and did not know for sure that he did. Smith was mentally unwell and under care. There was no evidence one way or the other that he was involved in Joan’s death. At an inquest it was noted that the mentally unwell can sometimes confess to crimes they had not committed. Joan’s killer has never been identified. She is buried in Hasting Cemetery. And not far away in the same cemetery is Arthur Smith. For our first post of the year we wanted to share an idea with you and hopefully make you think.

Did you make a New Year’s Resolution? Do you promise yourself you are going to what? Lose weight? Stop smoking? Be kinder? We’ve all made them - and how many times have you managed to do a bit - or haven’t actually done it at all. It’s hard. All the harder because we make resolutions about things that often mean making a huge change. At Genealogy Investigations we often talk about giving back - donating to a worthy cause, or organising this or that. The reality is life gets in the way, there are kids to wrangle, dinners to make, work to do and before you know it, all your good intentions have slipped away. So we’re not going to do any of that. Instead we are starting the New Year with a new idea. Do One Thing. We don’t want you to commit to new behaviour, to change your habits or to promise to do something and then never do it or even to do it more than once. We literally want you to do one thing. We don’t even care what it is, as long as it’s for the good of yourself and others. The Do One Thing idea started overseas - as a way of getting people to do something more ecologically sound. We wanted to take it one step further. Somewhere in your neighbourhood - or city, or street - is something that might need doing. For Deb, it's the rubbish dumped around her nearby park where she often walks. So Deb’s One Thing was picking up as she walks (and it's probably more exercise). For Fran it will be clearing the rubbish from her local beach. There is no limit to what your One Thing can be. What if you bought one can of catfood and put it in the SPCA bins at the supermarket. Just once. What if you took your old sheets to Women’s Refugee instead of chucking them away? What if instead of walking past, you said hello to that older person you see every other day? Or reused a refillable water bottle rather than using a plastic bottle? Try paying a compliment to someone. It makes their day. Donate blood. What if everyone just did One Thing? What might our world look like? And it starts the year with a win. Doing it means you started the New Year having completed one good thing. Then tell someone else - who do you know who can continue by doing their One Thing? Or share your ideas with us in the comments. See you Wednesday when we begin Grave Stories with an unsolved murder. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed