|

The beautiful car looked like something from the future.

Long and sleek with a huge fin at the back, it didn’t look like anything anyone in New Zealand had seen before. It was called Thunderbolt and between 1937 and 1939 it had broken the world land speed record driven by Captain George, E. T. Eyston. On November 19, 1937, on the Bonneville Salt Flats it went 312.00 mph - 502.12 km/h. Within a year Thunderbolt returned with improved aerodynamics and raised its record to 345.50 mph or 556.03 km/h on 27 August 1938. That record was broken in a week but Eyston took the Thunderbolt out again reaching 357.50 mph or 575.34 km/h. The car had been brought to New Zealand to be displayed in the British Pavilion at the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition in 1939. The exhibition was held in Rongotai in Wellington and thousands came to see the car. Then in the early morning of September 25, 1946, bales of wool stored in the largest of exhibition buildings caught fire. Stored with them was the famous car which was destroyed. Along with the car, the air force lost five planes in the blaze - two Tiger Moths, a Harvard and two instructional machines - and 18 Gipsy aircraft engines. The airmen sleeping nearby had to get out, leaping from windows. Fire crew rushed to the scene but all they could do was prevent the flames from spreading to other buildings. The blaze could be seen across the city and even days later, the wool was still smouldering. In today’s money, the loss was over $55 million. Because of the loss, police began an investigation, trying to pinpoint the cause of the fire. There were theories of spontaneous combustion as wool was prone to it, but there were no signs of that. Nearly two years later, seven former Air Force personnel were charged with arson over the fire. Four pleaded guilty while the other three were later acquitted. The group had been members of the fire patrol team at the time and they knew their jobs were to be disestablished once the station closed. They conspired to start the fire which they would then put out and demonstrate how indispensable they were. They were even wearing pyjamas under their uniforms to give the impression of how sudden it all was. When the fire got wildly out of control they were unable to put it out. Captain Eyston died on June 11, 1979 and is buried at St Mary’s Roman Catholic churchyard in Oxfordshire, England.

0 Comments

Watching the mushroom poisoning case in Australia has been fascinating and we thought about all the cases where food and drink has been used to kill.

Poisoning is not always easy to determine and sometimes it’s hard to hard to detect. Overseas, there have been numerous famous cases, including poisoned curry in Japan, poisoned cakes in Spain, soup in Japan in a nursing home and a serial killer called the Giggling Granny in America who killed 11 of her family members with different foods and drinks. And in New Zealand poison was most often put into drinks, although we have also written about poisoned chocolates and cake. But it's not often jam roll is the culprit. Although in this case, it wasn’t murder but terrible carelessness. Walter Nelson was only 25, when he, his wife Anneata and their baby went to visit her grandmother in Freeman’s Bay in Auckland on January 5, 1893. Like many good hosts, some baking had been done for the guests, among them was a jam roll made by Laura Webb, Anneata’s sister. The whole family - without Walter who was out - sat down for afternoon tea about 4pm. Most of them ate a bit of the jam roll and became ill. However, as they began to recover over the next few hours, no one thought about the jam roll being the cause. Walter returned later that evening and had his own piece of the jam roll. Shortly after he complained of feeling sick and decided to go for a walk to get some fresh air and visit a tailor’s shop. But he was worse when he came back complaining about being ill and his throat burning and he was given various things to make him vomit but by midnight it was too late and Walter died. The police were called in. The only explanation for why there was only one death was that all the others had thrown up and Walter had not. The jam roll - along with all the ingredients that were used to make it - were taken into custody for examination. It was quickly discovered the cream of tartar used in the recipe, which was printed in full in the newspapers of the time, contained almost pure arsenic. It had been bought from a local grocer James Boyle’s shop in Union Street. A whopping amount of arsenic was found in the jam roll and worse - a current cake baked at the same time but untouched - had even more. Boyle had bought the cream of tartar from an importer in one big container and had been supplying it to his customers who often brought in their own tins to put it in. The inquest asked several questions about the container the cream of tartar was in and how the arsenic could have got into it, but it remained unclear. Arsenic was also sold by the same importer. The theory was that one of the stone jars had previously been used for arsenic. A verdict of accidental death was returned. And Walter was buried in Waikumete Cemetery. Six months later Anneata gave birth to a son who she called Walter after his father. Sadly, New Zealand has a terrible road toll. As long as there have been cars in the country there have been fatalities.

In 1919, there were about 17, 000 in the country and for many were still novel. In Wellington, there was already a taxi service and trams running back and forth but the roads were still designed around horse and cart. Horses were still used to deliver milk for another four decades. So a road death was a big deal. Bevet Barker Williams was a taxi driver. He had picked up his passenger Mary Louisa Powell and was heading down Kent Terrace to Courtenay Place about 2pm. He was turning through the intersection when he hit Mabel Black, running her over. She died at the scene. The case went to an inquest and then to a Supreme Court trial. At the inquest numerous witnesses mentioned the speed Williams was going. Several said they thought it was going too fast. One witness thought Williams was going the grand speed of 15 miles an hour, which he agreed with. One thought the speed was not too fast for a street but too fast to turn into the intersection. All thought Mabel had not seen or heard the taxi coming as she was crossing the road. Alice Martin said she only saw Mabel realise there was a car and began to run at the last minute. Mary Powell countered that evidence. She had been in the taxi and at no point thought it was going too fast. The coroner at the inquest gave an open finding and Williams was charged with manslaughter and the case taken to the Supreme Court. The case was extensively covered in the papers - a death by car was rare enough to be fascinating. Williams had been a taxi driver and had his licence for about six months. He had never before had an accident. Williams said it was as he got to the intersection that he could see Mrs Black and he sounded his horn several times to warn her. He said she looked like she was going to stop then kept going, so he sounded the horn again. But Mrs Black made a mistake and thought she would out pace the car. Williams said he was already slowing but was unable to avoid to her. The jury was taken to the street to see where it happened and were able to see the close distances for themselves. It took the jury only an hour to find Williams not guilty of manslaughter. Mabel Black is buried in the Karori Cemetery. Picture from Te Papa’s photographic collection. Ella and Lily Cooke were travelling. Ella had finished her nursing training and the twins were enjoying a trip that had taken them to Britain via America and Canada before heading back to New Zealand in 1914.

They had intended it to be an adventure. By the time they had reached New York, war had been declared and the world as they knew it had changed forever. Ella and Lily had been born in 1881 to Henry and Sarah Cooke - the youngest of their eight children. Ella left school in 1907 and immediately went into nursing completing her training in Auckland before working at hospitals around the North Island, like Gisborne and Hawera before becoming the native health nurse in Ngāruawāhia. As their ship docked in London, Ella knew what she wanted to do and she offered her nursing services to the British Government. When they refused she headed to France working for the French Flag Nursing corps as a volunteer. Her first wartime hospital was in Bernay, near Rouen in northern France. She wrote home a lot, and it’s through her letters that we get a sense of how bad it was for so many. While in France she witnessed severe cases of trench foot, many of which required amputation. In a letter home, she wrote, ‘I am sure many people do not realise what this war means unless they could see these poor suffering men.’ After six months she was back in England and invited to join the Queen Alexandria;s Imperial Military Nursing Service reserve, training and nursing in England for a bit at Aldershot hospital. Her letters now spoke about how hard it was, saying they had too few staff and that she was responsible for 240 beds with only three orderlies to help her. In September 1915, she was sent to the No 17 General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. It was a far cry from the green countries she had been in. She was well liked and social and the chief amusements were excursions to view the Pyramids and the Sphinx, boat trips up the Nile and dinner at the Continental. Ella became a favourite with those she nursed described as happy and popular. Tragically, after two years nursing in Egypt, on September 8, 1917, Ella was walking to a friend’s house for dinner when she took a shortcut across a railway line and into the path of an oncoming train, and was instantly killed. She was buried with full military honours at Hadra War Memorial Cemetery in Alexandria. Her name is also on the York Minister window of the Five Sisters - one of the largest ancient stained glass windows in the world. When it was restored after World War One the names of the women who had died doing their duty were added. Admit it, at least once you rolled a Jaffa down the aisle (or under the seats) at the movies.

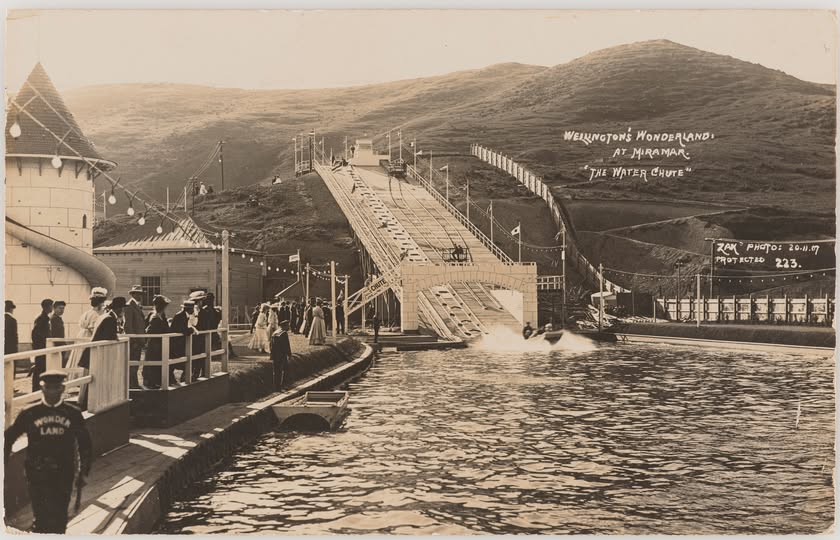

At one point it was almost a rite of passage if you went to the movies with your mates. And of course the famous Jaffa race down Dunedin’s Baldwin St. It’s not going to be so easy anymore with Jaffas - those chocolate orangey balls, the favourite of many - no longer being made and are to disappear from shelves. Sweetmaker RJs confirmed that they had pulled the treat saying they were unable to make Jaffas due to declining sales. It’s not known when the relationship between movie theatres and Jaffas came about, but the first New Zealand motion picture exhibitor was Alfred Henry Whitehead using Edison kinetoscopes. The pictures were often things like public events - like the opening of the Auckland Industrial and Mining exhibit. Whitehead was born on September 15, 1856, in Birmingham, England, to Abel and his wife Matilda. He came to New Zealand with his family when he was about eight. Around 1894 he began touring the country showing off his Edison phonograph. Then late the next year he began showing motion pictures - although the pictures could only be seen by one person at a time. He opened a kinetoscope at Bartlett’s Studio in Auckland where he used four machines at once. For one shilling he was showing four scenes - the barber’s shop, the fire rescue scene, the chinese laundry and Annabelle’s graceful butterfly dance. He later took the whole show on the road ending in Wellington where he sold the machines in 1897. He could likely see the end coming - the year before the first mass presentation of a motion picture was held in the Auckland Opera House where moving pictures were projected onto a screen. After a trip overseas to Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebrations in London, he married Ada Baker back in New Zealand. He brought back with him a camera to allow him to make his own motion pictures and he used prominent Auckland photographer W H Bartlett for it. It was Christmas Eve that year he screened the opening of the Auckland Industrial and Mining Exhibition. Alfred continued to tour, showing pictures to the public. He retired in 1908 and died on April 7, 1929 and is buried in Waikaraka Cemetery. Meanwhile, there are alternatives to Jaffas, including generic orange chocolate balls still available. Picture by Noom Peerapong. In January 1907, a young man calling himself Demos got on his bike, set it on fire and hurtled down the huge waterchute in Day’s Bay in Eastbourne, somersaulting into the manmade pond at the bottom.

The big waterchute, on loan from Miramar’s Wonderland theme park, was an attraction at the Williams Park in Day’s Bay when it was considered one of Wellington’s premier seaside resorts. The chute was a 67m drop and people could reach 50kmh on their way down. Usually people got into boats that plummeted down the chute and 5000 people a day went out to what was then the largest waterchute in Australasia. Days Bay was originally known as Hawtrey Bay before it was settled by George Day who brought his family out from Kent in 1841. Day was hired to look after the area and built his house and operated a ferry of sorts for early settlers crossing the harbour regularly. He and his family later settled in the South Island. It was James Herbert Williams who saw the potential of the area as a resort. He was a prosperous shipping owner who took his employees to Lowry Bay for pleasure trips using his own ships. He rebuilt the Lowry Bay wharf when it became dangerous at his own expenses. He also began to develop the area with playground equipment and a refreshment stand and in 1894, he took the chance to buy 125 acres of land in Days Bay and built another wharf. It soon became so popular as a day trip that wharf gates were built, Over time it continued to develop and building sites were put up for sale in the surrounding area. Days Bay House was built in 1903 for William’s company and run as a resort hotel, although it had only moderate success before it was sold and then operated as a school. The area was eventually bought by the Wellington City Council at the urging of the public in 1914. Williams was said to have been born in Melbourne but in fact was born at sea and registered there. He ran the shipping company his father had started, marrying Eliza and they had four children. During his time in Wellington he founded the Wellington Steam Ferry Company. It was his widowed mother Mary Ann Cox, already considered a great philanthropist, who gave a large sum of money to the Wellington City Council to allow it to buy the Days Bay resort. The Wonderland closed in 1910 after losing money and the rides and the water chute was sold to Auckland where it ended up at the Auckland domain for a couple of summers before being dismantled. Williams died just a year after Days Bay was sold, on January 19, 1915 and is buried in Karori Cemetery. It was just after the afternoon tea break on April 13, 1965, at the General Plastics factory in Kuripuni in Masterton.

The big factory’s workers had been at work the whole day, lunchtime had been taken and the 70 workers were now thinking about knock off time. At the 3pm teatime, most staff went on their break with just a few still working. Just as they were making their way back to their work stations, a massive explosion rocked the factory. It was so big and so loud that later, workers in different parts of Masterton both heard it and felt it rattle their buildings. At the factory, which was making buttons, the entire roof was blown off along with part of a wall. Fire then gutted nearly all of the factory. The fire brigade raced to the building but were unable to save it. It was insured for £37,000. Flames were said to have reached 60ft. Once the fire was out and the staff, who had fled the building, were counted, six were injured and four were missing. At an inquiry staff said they had noticed an odd smell before the explosion. Beryl Castle said she had asked a supervisor about the smell and he went to investigate but wasn’t seen again before the explosion happened. Beryl said she managed to get out through a hole in the wall where a window blew out. Richard Swanson said he also noticed a strong smell just before the explosion and came to just having escaped having the roof fall on him. Joan O’Hara told the inquiry that the factory was not well ventilated. In fact the explosion was caused by dust. Dust had collected for years in and under the floor of the factory and a short circuit in one of the button-making machines sparked the fire that caused the explosion. An expert who spoke to the inquiry, Percy Clark, said the dust was highly explosive. He had investigated various possible sources and had ruled out sources like light bulbs. He thought that the spark would have created the fire that spread like a shock wave igniting more and more piles of dust. It was not thought the company understood how dangerous the dust was. The commission of inquiry later recommended that legislation was put in place to regulate ventilation and accumulation of dust. The four people who died were Kenneth Bull, 32, Olive Victoria Parker, 61, Tilly Himona, 44 and Maisie Louisa Cavanagh, 51. All but Maisie is buried at Masterton’s Archer St cemetery. Maisie is buried at the Papawai Urupā in Greytown. When the Duke of Edinburgh - then Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria’s son, undertook a tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1868, he took a royal artist with him.

It wasn’t the done thing to use things like photography, which was not as common as it was even 20 years later. So Prince Alfred invited Nicholas Chevalier to come with him. Chevalier already knew Australia and New Zealand and was to go on to become a celebrated artist - along with his wife Caroline - of New Zealand landscapes. Chevalier was born in St Petersburg, Russia on May 9,1829, to Louis Chevalier and Tatiana Onofriewna. He studied as an artist in Switzerland and Munich while also studying architecture before going to London to study lithography and work on watercolours. After a couple of years in Italy he moved to Melbourne where he met Caroline Wilkie and got married. He worked as a cartoonist and illustrator. Then in 1863, he designed a dress for the governor’s wife that incorporated the Southern Cross along with a lyrebird inspired fan. She did not wear it in the end but the pair then collaborated on a present for the newly married Princess of Wales and came to the notice of the Royal Family. He first visited New Zealand in 1865 and arrived in Dunedin where he took a £200 commission from the Otago Provincial Council to travel the province and create paintings. The intention had been from the paintings to be exhibited at the Paris Exhibition in 1867 and help attract settlers. There is no record his paintings ever went to the exhibition but it did lead to the Canterbury Provincial Council to make him the same offer. He went to Lyttelton with his wife and they began a tour of the West Coast. Caroline wrote of the beauty of the region 'Immense trees clothed with lichens of many colors all hanging around their stems like grey beards & all looking very weird & as though they were hundreds of years old as they may have been.' After traveling around the Mt Cook area, Nicholas held an exhibition in Christchurch and then in Wellington before returning to Melbourne. He was then asked to create decorations for the visit of Prince Albert and then to travel with them by the Prince himself. He was close by when Prince Albert survived an assassination attempt in Sydney. Nicholas went with the duke on visits to Otago, Nelson and Canterbury and made drawings, then on to Wellington and Auckland, sailing by way of the East Cape. In Auckland Nicholas made detailed drawings of Māori artefacts in the museum. He accompanied the prince back to England via Tahiti, Hawaii, Japan, China, Sri Lanka and India. Back in England he held several exhibitions of his New Zealand work as well as being employed by Queen Victoria to record important state occasions, Nicolas died in London on March 15, 1902 and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, London. His work is in collections in Te Papa and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Ernst Dieffenbach thought Wellington was a bad idea. As far as he was concerned it was not fit to be a colony city.

Born Johann Karl Ernst Dieffenbach in Giessen in the Grand Duchy of Hesse in Germany on January 27, 1811, he had trained in the field of medicine and was a student during a time of great discoveries in the physical sciences, along with political reform which led to him becoming a political fugitive in Switzerland. After he was jailed there for two months for duelling he was expelled (although not before gaining his degree) and headed for England. It was there he met prominent scientists like Charles Darwin and took a position with the New Zealand Company as a naturalist. In 1939 he sailed for New Zealand on the Tory. Once here he began exploring, travelling through the Marlborough Sounds, the Hutt Valley, Taranaki, the west coast of the North Island and even spent four weeks on the Chatham Islands. He is considered one of the first European men to see the Pink and White Terraces. He also climbed Mt Taranaki. Dieffenbach became increasingly critical of the New Zealand Company’s land purchase scheme. His first look at what would become Wellington convinced him that they were selling unsuitable land. He also argued with them about his reports in which he meticulously recorded things like distances, temperatures for the new settlers. He is considered the first trained scientist to live and work here and he sent a huge number of specimens back to the Royal Botanic Gardens, the Kew and the British Museum. He is believed to be the person who coined the term greywacke for the sandstone of New Zealand mountains. In 1841, he wanted to make a complete scientific survey of the country once his contract with the New Zealand Company ran out and he convinced the governor William Hobson of it. But it was rejected when Hobson asked for funding. Dieffenbach returned to England where he published a book, Travels in New Zealand which gave accounts of life here and observations about the plight of the Māori before the rising tide of European settlement. He could see that the Māori way of life was threatened by the arrival of colonists. He worked as a translator and scientific jack-of-all-trades and tried to return to New Zealand but was unsuccessful. He was able to return to his birthplace, Giessen and eventually was nominated to the national assembly there but declined, instead becoming associate professor of geology at his old university, going on to be director. Dieffenbach married Katharina Emilie Reuning in April 1851. They had two daughters, Klara and Anna. Ironically his book helped promote more people to come to New Zealand which was absolutely not his goal. He died of typhus in 1855, probably on 1 October, and is buried in the Old Cemetery in Giessen. Richard Owen held a piece of bone in his hand. It was about 15cm long and he initially had no idea what it was.

He thought it might be from an ox since it was clearly part of a larger bone - probably a leg. He was sent bones by a variety of people finding them around New Zealand and at one point he had boxes of unidentified bones. In 1839, he had theorised a huge flightless bird but there was little evidence. Then missionaries William Colenso and William Williams sent two big boxes that intrigued Owen. On January 19, 1843, he picked up a huge intact femur and came to the conclusion it was part of a femur of a huge flightless bird. The discovery was astounding. The world of course, knew of ostriches and other big flightless birds, but nothing like the one Owen was suggesting. It caused a furor - here, in the boxes in front of him was bone after bone from that bird. The bones had come from Poverty Bay and were from a bird Māori called a moa. The bones were displayed, vindicating Owen’s theory and he gave the bird a name - Megalornis novaezealandiae - later changed to dinornis. The idea of a bird that stood 14ft or so tall captured the imagination. And one was reconstructed that people flocked to see. It was Owen who created the term dinosauria from which we get dinosaur. Owen was born on July 20, 1804, in England to a distinctly poor family and lost his father by the time he was five. He went to Lancaster Grammar school but did not distinguish himself and ended up joining the Royal Navy as a midshipman. When that was not for him he went to the University of Edinburgh to study medicine but was unhappy there and went on to Barclay School - the same school Charles Darwin went to. He became an assistant cataloguing the Hunterian Collection - specimens from famous surgeon John Hunter for the Crown. He had to identify and categorise it from scratch as the papers that had come with it were burned. It got him interested in comparative anatomy. From there his reputation took off and he is now considered one of the most outstanding naturalists in the world. Owen died on December 15, 1892 and is buried in the churchyard at St Andrew’s near Richmond in Surrey. |

AuthorFran and Deb's updates Archives

July 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed